No products in the cart.

Moonstruck

Near-Tragedy at Craters of the Moon

By Mike Medberry

In April 2000, conservationist Mike Medberry and several friends were hiking at Craters of the Moon, gathering information for then-President Bill Clinton’s Secretary of the Interior, Bruce Babbitt, who hoped to expand the approximately 54,000-acre national monument to 750,000 acres. While walking, Mike suffered a stroke that impaired his speech, among other after-effects. His mother moved from California to Boise to help with his recovery. The following excerpt from his book, On the Dark Side of the Moon (Caxton Press, Caldwell, 2012), reprinted with permission, describes Mike’s return visit to Craters a few months after the stroke.

One day in early summer, when she thought I was able and interested, Mom suggested that we take a roadtrip in Idaho. “Where should we go?” she asked.

“Ow bout Craters? I would like that.” I felt like Humpty Dumpty. I had taken a great fall and had to put together the pieces of this broken egg: confidence, communication, love, sanity, work, and memories. And all of it related to Craters of the Moon, where I had fallen and lain out on the lava for many hours. This was a harrowing memory, made more poignant by the time-sensitive ischemic stroke that had permanently damaged my brain. I say that my stroke was time-sensitive because doctors give stroke victims three hours to get the person to a hospital to treat him with a clot-busting medicine, before lack of oxygen kills the afflicted cells. It must have taken me eight hours to get to the hospital in Pocatello. We never spoke of this, but it reminded me just how precious time can be. I wanted to confront this fear and show my mother the beauty of Craters of the Moon, which I had worked to protect over the years.

A visitor enters a lava tube at Craters of the Moon National Monument. Photo courtesy NPS/BLM.

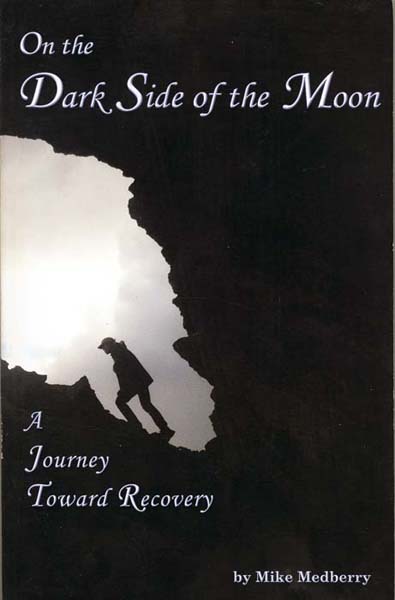

Front cover of Mike Medberry's book. Photo by Doug Schnitzspahn.

On a return trip, the author contemplates entering the lava fields. Photo by Doug Schnitzspahn.

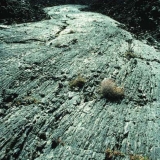

Dwarf monkey flowers at Craters. Photo courtesy NPS/BLM.

Aerial view of lava flow. Photo courtesy NPS/BLM.

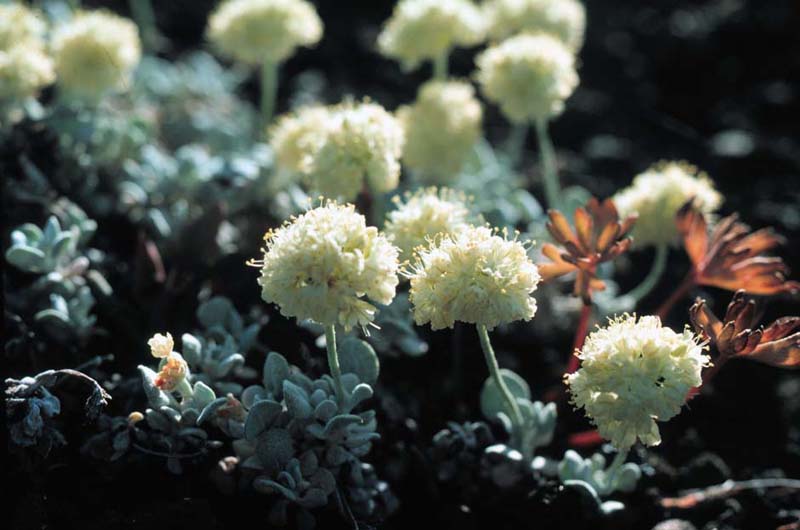

Dwarf buckwheat. Photo courtesy NPS/BLM.

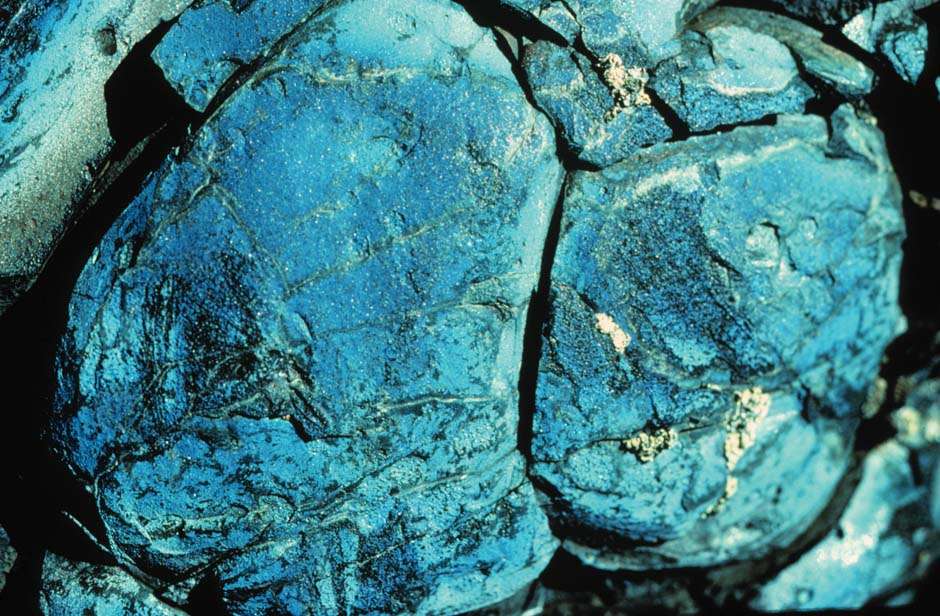

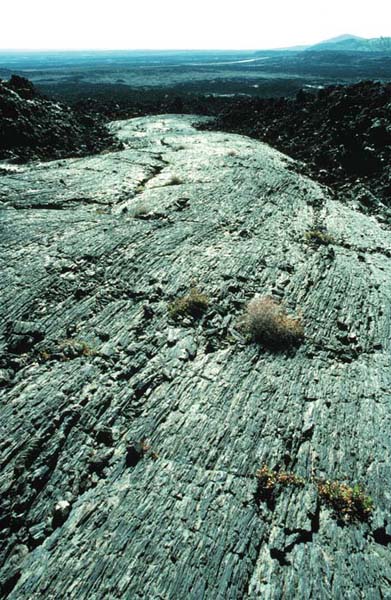

A lava river. Photo courtesy NPS/BLM.

The Inferno Cone. Photo courtesy NPS/BLM.

A cave entrance at Craters. Photo courtesy NPS/BLM.

Pine tree at Devil's Orchard. Photo courtesy NPS/BLM.

The author in the lava fields. Photo by Doug Schnitzspahn.

“Yes, that would be a good place to go. I haven’t seen it yet, and I know you love Craters of the Moon. I’ll bring Tika along.” Tika was a tough fifteen-gallon barrel of a dog, a cattle dog who was Mom’s constant companion.

“It’ll b’ hot,” I said. Mom offered to drive, and I suggested that we stay in the one-buggy-town of Carey. My driver’s license had been suspended after the stroke, but I got it back by passing a driving test while I was still unable to speak clearly to the examiner in Boise. I pointed when she asked me where I was going and shook my head when I should’ve said no. I smiled gratefully when she said I had passed. Still, I was relieved when my mother said she’d drive. By nightfall we found a cheap motel in Carey, and I was fast asleep when the door was nearly bashed down.

“Jenny, let me in!” came the drunken voice at our door.

“Get lost!” Mom said in her toughest, lowest voice. “Go away!” I was definitely awake now. My mother’s voice always became lower when she felt afraid.

“Come on, let me in!” The door was thin as cardboard.

“There is no Jenny here,” Mom growled. A bare lightbulb glared starkly as she pulled a string above the bed.

“Oh come on, let me in,” he pleaded. More pounding.

“Get lost!” Mom parted the curtains and peered out the window.

“Mike, he’s just sitting there,” she whispered tremulously.

“He’ll go,” I said. But he didn’t.

“Get the hell out of here,” Mom bellowed, “or I’ll call the police.” Tika started barking wildly.

“No!”

“Then I’ll call the police.” She spoke in an even deeper voice, as the little Australian cattle dog continued her piercing barks.

There was silence from outside the door for a moment. “OK, OK,” he muttered. We heard his thudding footsteps recede.

“Now let’s get some sleep,” my mother said as she pulled the light string.

I had done nothing to get rid of him because I felt I couldn’t speak well. I’d left it to my mother, and I felt like a coward. Lying in bed, I was eager for daylight.

As I lay there tossing and turning, I thought about my mother’s courage. It had served her all of her life, through growing up in the poverty of central California during the Great Depression, while serving as a medical technician in Japan after World War II, having a hysterectomy in a lonely hospital in Washington, D.C., losing her husband to a stroke and brain cancer, then almost losing her son in a similar way—and maybe, most of all, through being raped in her youth.

These were things that my mother never forgot, although she didn’t often bring them up. They defined for me who she was, and why she lived with compassion and fear, understanding and joy. We talked about her life now and then over the years when we were driving somewhere together, and in Boise when we had time. When I asked her why she never remarried she replied, “No one ever asked me after your father died.” And that was that. Of course, it wasn’t. She’s an attractive woman and everyone gets lonely, but it was a closed question. I know this much, however: she wanted the best for me, and that was why she moved to Boise. I felt her love and tried to return it.

In the morning, Mom asked what we should see in Craters. She had outlived the night and was ready to go again. Over breakfast we pulled out a map, and I suggested we drive the seven-mile loop road from the visitor center. From there, we would take a short hike. I wanted to prove that I could still make my way and show my mother that I was not a useless son. I offered to drive.

I drove half the loop and parked at the southern end. I proposed that we walk toward a group of tree molds which had retained the shape and texture of the tree trunks that were incinerated by flaming lava two thousand years earlier. I pointed out a well-defined trail, but my mother wanted to stay in the car. “It’s hotter than hell,” she said, “and the place looks awfully desolate. It looks like the Sahara. Tika and I will turn on the air conditioning and wait for you. Don’t go very far.”

I set off on my own, examining minuscule purple flowers and feeling the rough path through my boots. After half a mile or so, I turned around, afraid of triggering another stroke. I headed back to the car, where my mother was waiting and worrying. I told her that I had looked out across the boundary of the national monument and imagined expanding this protected territory to bring in much of the surrounding land. This hike seemed, she said, the first step on a thousand-mile journey.

I found that navigating accurately with a compass was no problem for me even in the anonymous expanse of lava. That came as a surprise, because a doctor warned me that my sense of direction might have been obliterated by the stroke. He told me not to go out wandering alone. But what would my future be if I couldn’t find my way along a simple trail? I had to be able to figure out where I was in a landscape, because I had always loved finding deserted, empty stretches on long runs and hikes. Now I was confident that I could find my way around and get back, even if only on a short route. That was enough for now. I could read and follow a map. I could identify places to go, and places that were important to avoid.

We stopped often to look at the landscape along the seven-mile road. The terrain of tortured chunks of basalt in the lava flow reminded me of bodies being stretched like taffy in the heat of melting rock. In another place along the road, a football field-sized expanse of cinders the color of burnt sienna had fallen a thousand years ago when a cindercone blew up nearby, or so said a National Park monument sign. We parked and both of us walked out into the field of tiny cinders which were as light as popcorn. They made squeaking sounds under our feet. Little grew in these queer places except the white webs of a few pioneering plants. Tall cindercones, looking like large piles of black sand, stood against the eleven thousand-foot Pioneer Mountains in the background, a drama of severe contrasts that shifted under creeping shadows of clouds. Long grasses swayed on the faraway mountains, conveying motion that echoed the sweep of time. In the foreground, tiny, brilliant magenta monkeyflowers and balls of dwarf buckwheat bobbed in the wind. This stillness and beauty had prevailed for millennia, bringing awe and peace to those who beheld the scene. My mother and I walked along in silence but for the squeaking of cinders underfoot.

A well-worn trail just off the road, ascended Inferno Cone and brought to us to a panoramic view of the receding land. I took a quick trip to the summit by myself, and from the top I saw flows of lava in shades of gray and black, the darker lava marking more recent and rugged flows with patterns cutting the jigsaw relief of the land. Big Southern Butte rose abruptly from the Snake River plain ten miles away, and gave additional dimension to this piebald view. Behind it, Borah Peak rose to more than twelve thousand feet amid the high Lost River Range in twisted cirques and ridges. In the farther distance, the Teton Mountains seemed small and faint, a pointy, incongruous alpine setting, crowning the vastness of closer, coarser lava flows. I drank in the view and climbed back down to the car, and we drove on a couple of miles to where the Caves Trail began.

I had wanted to see the caves in Craters since I first read about them, twelve years ago, in a 1924 National Geographic article by Robert Limbert. Limbert, a part-time explorer and writer, earlier was one of the first to map out this eerie landscape of lava, over a pair of expeditions in 1920 and 1921. A lively storyteller, gunslinger, and all-around flamboyant character, he popularized the name Craters of the Moon and championed protection of the area until President Coolidge designated the original 54,400-acre national monument in 1924. Limbert’s National Geographic article was part of his public relations campaign. His descriptions of his marathon journeys caught my imagination, though I had to admit the way that he died—of a stroke—made me shiver. At least he wasn’t hiking in Craters of the Moon at the time.

Mom wanted to stay in the car with her stout little dog. It was a short hike from the car to Boy Scout Cave, so I went alone. That cave comprised a dark, cramped tunnel opening onto a natural ice rink that a young skater could glide around with room to spare, or so said a second National Geographic article. I saw only a shrunken pad of ice that would tempt none but readers of that article to bring a pair of skates along. It disappointed me. The enormous Indian Tunnel, a quarter of a mile away, descended as a gash into the ground. As I walked in, light shone in oblique cracks, splashed like quicksilver on the floor. It dazzled me.

The Devil’s Orchard, near the parking spot where I began, was a befuddling cluster of tall demonic basalt structures that had been carried along on flowing lava. Juniper trees, redolent of gin, grew in hollows and humps of ground beside the dancing devil’s den. Pahoehoe lava dried in the form of pythons coiling around each other, daring me to walk on their backs to make a shortcut. In forty-five minutes, I was back at the car with my mother and Tika.

“How was it?” Mom asked. Tika panted.

“I feel renewed.”

From the end of a spur road jutting off the loop near Buffalo Cave and Broken Top Mountain, we could see part of the Craters of the Moon Wilderness, created by the passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964. The Prairie stretched out as far as the eye could see, and I understood why this kipuka was named The Prairie. It is a lovely, shabby, shrubby, grassy area dotted with pyramidal buttes and cones, but it is surrounded by lava. It was a glorious place to be, and I felt it calling to me when my mother and I turned to leave.

On the way back to the visitor center, we saw pure black lava and large cracked blocks that looked like Volkswagens left out in a rock junkyard beside the road. We passed the Blue Dragon lava flow, with its unique, iridescent glow that is created by a film of titanium left on the surface of the rock as molten lava cooled. This landscape is as weird and unknown, as numbing and spectacular as tundra on the North Slope of the Brooks Range in Alaska, in which I’ve hiked. It is similarly arduous for hikers moving across hummocks of melting land as across a’a lava to make progress.

My mother drove us out of the monument, across the duotone lava toward Ketchum, and onward to the distant, developed landscape of Boise. Back home, we rested after our long, strange journey.

“Did you enjoy it? Was it pretty?” she asked.

“Yeh, kinda,” I replied. “Da wak was go-od.” Then the conversation drifted, and we talked about California and all our relatives and friends who lived there. However, my mother and I never talked about long past arguments between us and all the things that had separated us for so many years. The angry comments we’d made to one another, the painful things we’d done—these petty things were done; they had vanished. I was chastened by the stroke, and now the past didn’t matter at all.

Out of the blue my mother said, “Mike, you’re my son. I would do anything to help you.” I was silent. She had come to Pocatello, then to Boise, had given me beautiful furniture for my house, had sewn the curtains, and helped arrange the financing for the house. And what had I done to deserve that kindness? At length I said, “I love you, Mom.” The words came out all right, and we took another step on that thousand-mile journey.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only