No products in the cart.

The Absence of Assorted Things

Where Nothing Is Everything

By Elizabeth Lee

The onset of college this fall makes me feel as though I have just begun to appreciate Boise. Having spent three weeks on the East Coast, and with the prospect of four metropolitan years ahead, the respite of summer comes as an unexpected welcome.

For so long, I’d been dying to leave the small pond of Idaho for larger pools, yet only now do I fully recognize the calm of these gentle waters in comparison to the busy turmoil of vaster waters, teeming with larger frogs. I thought I’d been suffocating in the smallness of Boise, yet New York, breathtaking as it is, leaves me gasping for air.

So today I savor the fresh air, shopping at the Saturday market, strolling in the rose garden, or simply driving with my windows down. I recall swimming in Payette Lake, hiking Table Rock. I remember one time driving to Lucky Peak with Audrey in mid-March, the sky an ugly gray, the wind making our jackets flap.

“Why are we doing this?” I asked her again.

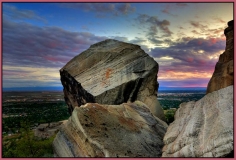

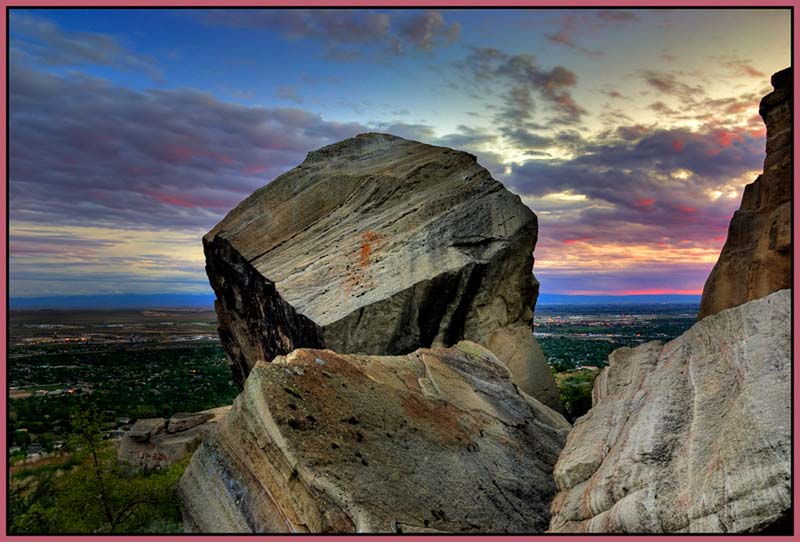

Now I know why. Because Boise is the place to swing legs over Table Rock, burn shoulders under the sun, throw pistachio shells at the skyline. This is the place to lazily drape tan bodies across rafts, narrowly missing the trees that bow over the Boise River. This is the place to sit on a wall and watch the reservoir do nothing, then drive back home. This state is liberating because there is, in a sense, nothing to do here.

Boise High School. Photo Boise Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce.

Sweets shop, Boise. Fiona Montagne Photography.

Boise foothills. Photo by GPS.

Sandy Bay at Lucky Peak Reservoir. Kenneth Freeman photo.

Moon over the city. Charles Knowles Photo.

Rafting the Boise River. Photo by Chal Gouker.

Rock quarry at Table Rock. Charles Knowles photo.

A bloom in the rose garden at Julia Davis Park. John Sumsion photo.

Boise Train Depot. Charles Knowles photo.

When I went to New York, the world moved constantly, changing and rearranging itself, pressing forward to the next engagement. In Boise, everything is still, and sweet, and slow, as though paused. There is time to stop by the river, to take an impromptu hike, to lie on the grass in the park and read a novel.

“What’s it like there?” outsiders ask me, curious about this enigmatic state that could just as easily be Iowa or Ohio. “Is there anything to do?”

Yes and no. There is nothing, so there is everything. You will not find Japanese ramen shops there, or even a Dunkin’ Donuts. But you will see the Morrison Center, where I take my violin lessons. You will see the Idaho Taekwondo Training Center, where I earned my black belt. You will see Boise High School, sans parking lot—a constant pain to all the late high schoolers in early morning. You will see the Capitol building, where our chamber orchestra holds its annual holiday rotunda concert, a longstanding tradition. You will see the city that gave me countless opportunities, creating the student I am today, and instilling in me the concept of the citizen I want to be tomorrow. You will see the big bookstore on Milwaukee Street, which I frequented nearly every week, cracking open books to escape to some other world, unaware of the greatness of my surroundings.

And you will see the world from above, when you climb into the foothills and regard not a sprawling metropolis but a small city, content with its size and proud of its community.

When my grandfather visited, I thought he’d come back. I thought, when he comes back, I’ll take him to Table Rock, and if he can’t hike it, we’ll drive up. We can watch the Boise lights turn on as the dusk fades, like we watched the fog rise on the top of Pike’s Peak. When he comes back, we’ll take morning walks on the Greenbelt and get coffee downtown. When he comes back, we’ll go fishing together and eat his favorite spicy fish stew for dinner.

But he never came back. Instead, I went to him, in a California nursing home, watching the life drain out of him as the morphine drained into him. He was frail, wispy on the edges as though he were fading, yet his ribs jutted out at sharp angles.

When he died, stories of my grandfather resurfaced: how he woke up early in the morning to learn English from the American radio, how he worked on a U.S. military base during the Korean War and later moved to America when he filled out his friends’ paperwork and decided to come along. How his hard work opened doors for him—and for me.

I thought about how he left the rice paddies for the Vietnam War. How he moved to America. I wondered if he missed Korea, if he missed home. Or maybe, I thought, maybe he brought home with him.

The word “home” has a different meaning for me now.

Home is not a house. It is the foundation beneath that house, the hands that built, brick by brick, the stability on which I could erect my own fortresses. Home is family. Home is my hand interlocked with my grandfather’s. But if home is the foundation, the background, then Boise, too, is my home.

My grandfather’s hard work in the rice paddies and his determination to leave them, to seek something better, fueled him, shaped him. Our origins are important. They make us who we are. This state is my origin. Idaho has made me who I am.

Boise, I think, has taught me to count my blessings. To know that the days are numbered and sometimes people do not return. To realize that there is richness and there is richness, and they are not the same. I am rich in the community that supports me, that provides the opportunities to play in orchestras and write for magazines and volunteer in sustainability. I am rich in the foothills and the river and the stars that are visible even downtown.

Some people flaunt their big cities, their diversity of food and access to any and all conveniences, but they forget the passing of the minutes—how quickly they lose time. They forget spontaneity, instead walking a clock that revolves around schedules. They forget the purchase of solid rock beneath their feet, the crash of water in their ears . . .

They forget the smell of fresh air.

So this is my thank you letter, dear Boise, for being a wonderful teacher. Thank you for reminding me to savor the sunshine, to taste the wind. Thank you for giving me the absence of assorted things rather than the presence of them so that I appreciate what I have and appreciate more what people take for granted.

“Audrey, why are we doing this?”

“I don’t know. Just for the heck of it.”

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Register & Purchase Purchase Only

Register & Purchase Purchase Only