No products in the cart.

Just Out Last Millennium

Idaho’s Oldest Books

By Alessandro Meregaglia and Gwyn Hervochon

Last year, when Boise State University hosted a traveling exhibit featuring Shakespeare’s First Folio, it was the first time the 1623 book had visited the state.

As librarians and archivists at Boise State’s Special Collections and Archives and two of the primary organizers of the exhibit, we could not have been more thrilled to witness the enthusiastic response of nearly ten thousand people, from as far away as Coeur d’Alene and American Falls, during the month-long event.

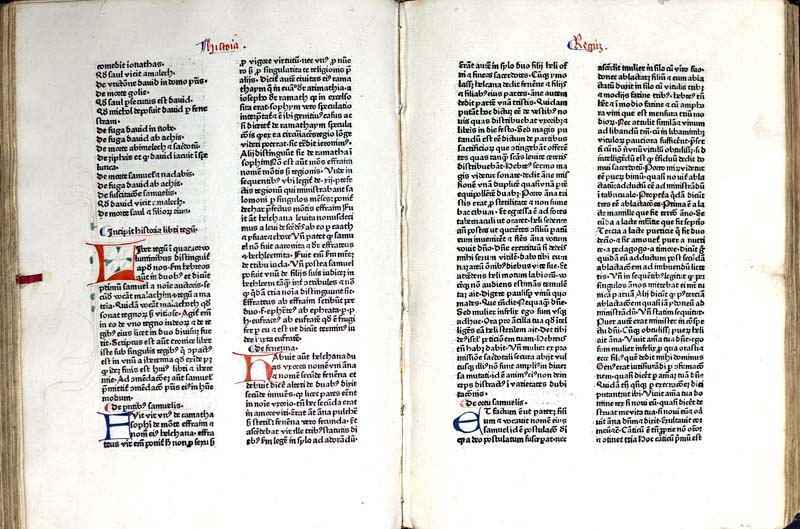

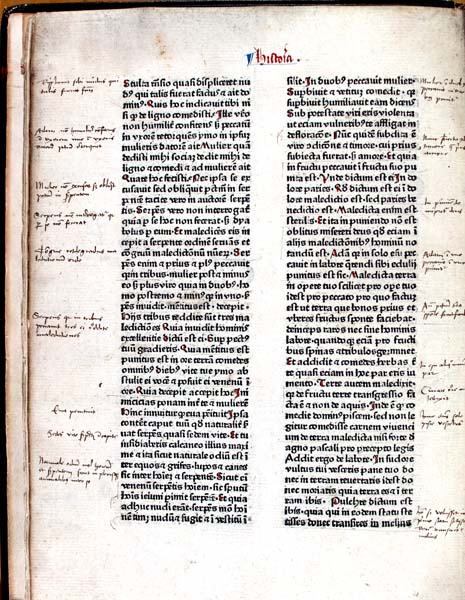

We knew this wasn’t the oldest book in Idaho, but it got us thinking: what is the oldest one, and how did it arrive in this state? While it’s likely there are rare book collectors who have old books in their private collections, we wanted to find out where the oldest publicly accessible books are. So, we contacted every public and private college and university library in Idaho, plus the State Archives. The results were interesting: BSU’s Special Collections and Archives owns the oldest complete book, a 1470 edition of Historia Scholastica by Petrus Comestor. He was a 12th-Century historian, and this book was considered an important work of Biblical scholarship during the Middle Ages.

Alan Virta, former head of Boise State Special Collections, told us it was required reading for scholars until the 18th Century. Boise State’s copy of Historia Scholastica is also an example of incunabula (from the Latin “cunabula” or “cradle”), which refers to any book printed in Europe before 1501. Books of that age are especially rare.

Historia Scholastica, courtesy Boise State.

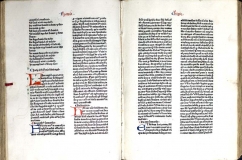

Dialogorum Libri Quattuor, courtesy University of Idaho.

- U of I - Middle.jpg)

Dialogorum Libri Quattuor, courtesy University of Idaho.

- U of I - Title Page.jpg)

Gutenberg Bible leaf, courtesy College of Idaho.

Historia Scholastica, courtesy Boise State.

Marginalia, Historia Scholastica, courtesy Boise State.

The book, which weighs just under six pounds, has a contemporary binding of unimpressive brown leather, which means the original 15th-Century binding was removed and the book re-bound in a previous edition. The text is printed but an embellishment to each page is that the first letter of every paragraph is hand-colored. Handwritten marginalia, in Latin like the text, appear throughout book. We get requests from patrons to see the book, but not as often as you might think, and few, if any, have asked to read it. We display the book when we showcase highlights of our collections, and a Boise State Latin class visits annually to view the book and to work on its translation.

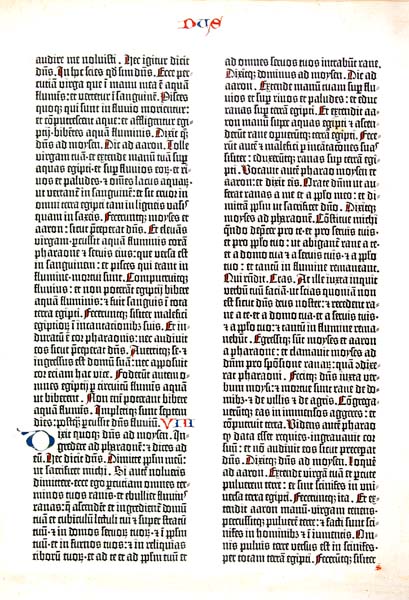

Despite Boise State having the oldest complete book, both Brigham Young University–Idaho’s Special Collections and Archives in Rexburg and The College of Idaho’s Robert E. Smylie Archives in Caldwell own a leaf (a single page) of the Gutenberg Bible, the first major book printed in the West with moveable metal type. Printed in either 1454 or 1455, the Gutenberg Bible was the result of a major innovation in the world of printing. With the advent Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press, books could be produced with relative quickness. Prior to the printing press, every book had to be written out by hand.

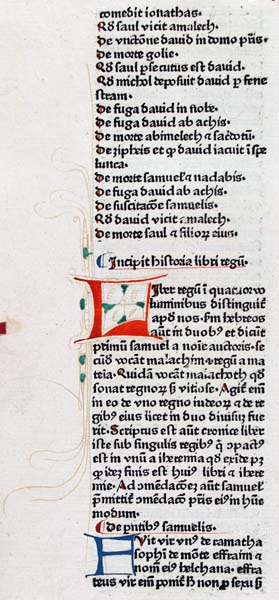

The fourth Idaho university to own incunabula is the University of Idaho’s Special Collections and Archives in Moscow, which owns two: a biography of Pope Gregory I, Dialogorum Libri Quattuor, published in 1492 in Venice, Italy, and Quarta pars Lyre by Nicolas de Lyre, published in 1497 and printed in Nuremberg.

All four of these universities acquired their rare materials during the 20th or 21st Centuries. Some were purchased while others were donated. Boise State acquired its incunabula, Historia Scholastica, in 1955, thanks to the efforts of the school’s librarian, Ruth McBirney, who traveled to Europe explicitly to purchase rare books and other items for the library’s special collections.

The College of Idaho received its Gutenberg leaf as gift from a bibliophile who also happened to be a student.

In addition to its Gutenberg leaf, BYU–Idaho also owns a leaf from the Nuremburg Chronicle, published in 1493, which tells the story of human history as described in the Bible. BYU–Idaho Special Collections Librarian Adam Luke explained to us, “Both items were purchased as a part of our collection of the history of writing and recordkeeping. It’s a representative collection, in which we acquire items that represent certain key moments in the history of recordkeeping. We use the materials frequently in orientations for multiple classes that come to Special Collections for instruction.”

Rare books such as the ones described above are important for more than just the words on the page—which, more often than not, are in Latin, and thus difficult for most modern-day readers to understand. As Luke indicated, these books are important artifacts, because they tell us about the history of printing as well as the history of the time. Even though the Gutenberg press made producing books easier, it was by no means a simple process. Printing books was expensive. Thus, studying how books were produced, used, and valued gives insight into the culture.

Idaho universities also own other old books. In addition to incunabula, half of Idaho’s higher education institutions have books from the hand-press period, which ended around 1850 with the mechanization of the printing press. We should also clarify that we were hunting for the oldest book in Idaho. The College of Idaho, the State Archives, and the University of Idaho all own cuneiform tablets produced thousands of years before the invention of the printing press.

Regardless of where you live in Idaho, stop by one those institutions and ask to see their oldest books. We think you’ll be fascinated by them: the paper is much sturdier than modern paper, the binding is hand-sewn, and the overall construction of the books is different yet surprisingly similar to books produced today. Despite popular depictions of archives, you do not have to wear gloves to handle Boise State’s Historia Scholastica. The book is stored in our vault in a climate-controlled room.

Even though the First Folio’s appearance in Idaho has already passed, Idahoans can still visit one of these universities to see a book that’s more than five hundred years old. If you’re careful, they might even let you touch it.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Register & Purchase Purchase Only

Register & Purchase Purchase Only

- U of I - Middle.jpg)

- U of I - Title Page.jpg)

Comments are closed.