No products in the cart.

Indian Cove—Spotlight

A Nick in the Desert

By Diana Hooley

A strong agricultural state like Idaho has hundreds of little farming communities, but not many can lay claim to two significant historic trails running through them. Indian Cove may not have a post office or a gas station, but both the Oregon Trail and the Centennial Trail cut across the farm fields and sagebrush plains of our valley. Not that this fact alone commends Indian Cove. Many people have commented on the wild and rugged beauty of the area and on its niche-like quality, tucked as it is next to the Snake River Canyon.

Forty-six years ago, when I first met my soon-to-be husband, Dale, I had a confusing conversation about where or what Indian Cove was exactly.

“Let me get this straight. You went to school in the town of Glenns Ferry and you pick up your mail in Hammett, but you live in a place called Indian Cove.”

I looked at him carefully to see if I understood.

“You’re used to city and towns back east. Just wait. You’ll see,” he smiled, confidently forecasting a future with me in this Indian Cove place.

We did have a lifetime together, and I eventually did understand about this farming valley. The first time I came here in 1974, I stood in a potato field listening to the repetitive “tuw tuw tuw” of pressurized sprinklers shooting water around me. Things were growing here—and yet at the same time it was so peaceful. I could get attached to such a place. Lunch was at the house of Dale’s parents. We had iced mint tea and baked chicken on a picnic table beside their home. When I stood up, I could see a sliver of the Snake River beyond the alfalfa field. The canyon rose in the distance, a monolithic wall of rock and sagebrush.

“Where else could you find a prettier place to live?” my long-time neighbor, Bob Rippe, asked me once. That day, Bob stood in his farmer coveralls on his big lawn as his eyes swept the boundaries of Indian Cove from the river canyon to the lush green farm fields spreading south to the desert.

Where indeed? It wasn’t surprising that I was immediately enchanted by Indian Cove. I’d grown up in dreary, industrial Indiana outside of Chicago. I’d never experienced basalt cliffs, soaring eagles, and spectacular sunsets. Nor am I the only one from the Midwest to venture here and decide to stay. Most of the early settlers arrived from Chicago, Indiana, and Ohio.

Captain Oberlin M. Carter is referred to as “Cap’n Carter” in an unpublished collection of family histories called Indian Cove Memories, which was assembled for a 1990 community reunion. Cap’n Carter came from Chicago in 1910 and developed an irrigation system for the valley. Good thing, too. Indian Cove gets less than eight inches of rain most years. Old-timer Claude Barber first came here early in the century and wrote this poem about the valley:

Oh, the land that lies before me is an empty desert plain,

Where the clouds float around moth eaten, ‘tis a land of stingy rain,

There never was any timber or any sort of grove,

There’s a little nick in the desert that is known as Indian Cove.

Dale Hooley (far right) with other family

members, 1966. Courtesy Hooley family.

Amos Shenk, Sr., with sturgeon caught by

his son Dave. Courtesy Hooley family.

A hay stacker, invented by Dale's father. Courtesy Hooley family.

Marylyn Hooley with the family's new tractor,

1940s. Courtesy Hooley family.

The Hooley brothers. Courtesy Hooley family.

Indian Cove's Idaho Centennial Trail marker. Diana Hooley photo.

Cap'n Carter's east end pump house. Diana Hooley photo.

Snake River Canyon at Indian Cove. Diana Hooley photo.

Indian Cove's church in the early 1950s. Courtesy Hooley family.

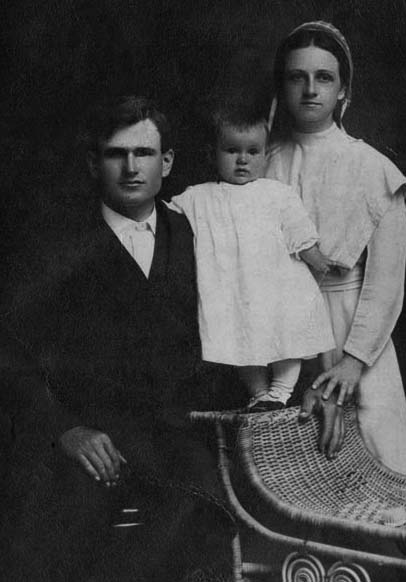

Paul and Alta Hooley with Eloise, 1916. Courtesy Hooley family.

Before Carter’s irrigation project, the few settlers here used waterwheels on the river to draw water for their ditches. The area was called Brown’s Flat after a Mr. Brown, who ranched the valley in the late-1800s. Writing for the Owyhee Outpost, Joshua Sven Lunn said Carter was the man who changed Brown’s Flat to the more glamorous-sounding Indian Cove. There was some merit in the name change. For hundreds of years, the valley was wintering grounds for native tribes, most likely Shoshone and Paiute. More protected by the canyon from winter weather than neighboring lands are, the valley draws deer and other game.

Lunn also noted that Cap’n Carter, who might be considered Indian Cove’s founder, was a convicted felon. This may have had something to do with his problematic irrigation project. Though Carter graduated at the top of his West Point class in 1880 and was part of the prestigious Army Corps of Engineers, the New York Times reported he was sent to prison for embezzling millions of dollars from the federal government. In Indian Cove, Carter had limited success. Pumps were installed and four canals at different levels were built, including a two- hundred-foot-high canal that extended fifteen miles through the valley, around bluffs and over hills. By 1912, there was enough water in one of the canals to irrigate the east end of the valley. But many of the early settlers were forced out because Carter sought to extract exorbitant fees to pay for the bond he obtained to finance his irrigation project.

Just before I came to Indian Cove, Dale took me on a date to see the movie, Fiddler on the Roof. Later, he said Anatevka, the tiny farm village portrayed in the movie, and its inhabitants, made him think of Indian Cove.

“Why?” I asked. “Anatevka is in Russia, for one thing, and for another, it’s Jewish. I don’t see the connection—other than the people there farm and raise animals.”

“Indian Cove and Anatevka are both isolated from the outside world,” he replied. “So community and tradition are really important.”

Now that I’ve read several journals and histories of Indian Cove, I see how spot-on Dale’s observation was.

After Carter lost interest in the cove, more settlers moved in, bringing their own cultures and traditions with them. When the Pancoast family came from Indiana in 1918, they had little farming background. Shortly thereafter, the Johnson family followed from Chicago, and as Swedish immigrants to America, they brought old country ways with them. Other families came and went and then, in 1927, a Mennonite farmer named Aaron Brubaker moved with his family to Indian Cove from Ohio. Aaron’s relocation here was soon followed by a steady stream of Mennonite farm families throughout the 1930s. Various ethnic and religious traditions all came together in our isolated little valley, and although there were differences, these farm folk were God-fearing and of the same mindset in one sense: you had to work hard if you wanted to succeed in the dry desert climate. Their industriousness reminds me of lines from a spoof song written by my husband’s maternal grandfather in the 1950s. The tune is to the old hymn “Oh, Beulah Land.”

I’ve reached the land of corn and hay, of cattle, sheep, and honey sweet.

I got my farm thru F.H.A., and now I’m busy night and day.

Oh Idaho, sweet Indian Cove, as on the highest rim I rove,

I look away across my field, and wonder what my crop will yield,

And then I view my stacks of hay, and now I know I’m doomed to stay.

In Fiddler on the Roof, it was not always easy to find a good mate, a good match, in a small remote village like Anatevka. So too, did love have its ups and downs in Indian Cove.

Katie Lehman was twenty-six and living on the river with her Uncle Ed and Aunt Martha Stevens when she met a rough, ex-gold miner and all-around ranch hand, Claude Barber. Claude was forty-two, and after he saw Katie, he couldn’t keep his mind on work. He told his friends he had “other fish to fry.” Katie said of their romance, “It was love at first sight.” In 1920, Claude proposed marriage to her in a boat on the Snake River, and the two lived the rest of their lives in and around Indian Cove.

Leona Brubaker (daughter of Aaron), was not so lucky in a brush with love she described in her 1927 diary. Leona wrote about going to the Indian Cove “literary” with the rest of the community. The literary was a night when the community gathered to watch a one-act play. Apparently, Byron Stevens, Katie Lehman’s cousin, was trying to court Leona at the time. He’d given her three boxes of chocolates. Leona wrote she was happy to take Byron’s candy, but she wasn’t really interested in him. Her last word on Byron in her journal was, “Ha!”

In 1919, a new school was built at Indian Cove with a real school bell brought all the way from Ohio. In 1935, shortly after my husband’s grandfather, Paul Hooley, came to Indian Cove, he began making plans for a water system on the west side. Water was always a problem on that end of the valley, which hadn’t been reached by Cap’n Carter’s canal. Finally, in 1941, the west end pumps were turned on, and the farms there came under irrigation. In 1950, a large new Mennonite church was constructed with timber left over from the Anderson Ranch Dam project above Mountain Home. With sufficient water and a growing community, the cove’s farmers were able to rise above subsistence farming to finally realize a profit. The men worked together on haying crews to cut and rake hay and then stack it with the help of tall hay derricks.

These hard-working folk also found time for fun.

“Dave (Shenk, one of the early Mennonites) loved to fish for sturgeon in the river,” my husband told me. “Carl and Sigert Johnson liked to fish, too. If they were out in the field working and needed a break, they’d get their poles and head out.

“Every Fourth of July when I was growing up, we got together for a big picnic with watermelon and baseball games. We drove up to the mountains where it was cooler and usually had our picnic there.”

There also were bound to be disagreements and rebellions over the years in such a small community. The traditions that hold people together often can be the very ones that eventually pull them apart. In Fiddler on the Roof’s village of Anatevka, a Jewish daughter is shunned by her family and people for marrying a Roman Catholic. In Indian Cove, Aaron Brubaker’s grandson, David Hamilton, went against Mennonite teachings about pacifism to enlist in the army. Mennonites interpret literally the Old Testament commandment to not kill, and they do not participate in wars. Young men in the church register as conscientious objectors. For his disobedience, David was excommunicated by the church in Indian Cove.

People in the valley never experienced being forcibly removed from their land in an ethnic cleansing as did the Jewish villagers of Anatevka, yet there were other sufferings and tragedies. One day in 1922, Karl “Ed” Johnson, who had recently arrived in the cove, was driving his wagon to Hammett with his two children, Carl and Edith. They hadn’t yet reached the ferry to cross the river when a thunderstorm blew in and lightning struck the wagon. The horses went down, and the electricity traveled up the wet reins, killing Ed instantly. Carl and Edith survived, and went on to live long full lives in Indian Cove.

My husband’s family, the Hooleys, also experienced an unexpected loss. In the fall of 1938, Dale’s grandfather, Paul Hooley, had just moved into a little house on the west end of the cove with his wife Alta and their children when he suddenly died. He was only forty-five years old.

“My grandfather woke up one morning, and they said he acted funny. It was a blood clot in his brain. Strange thing: there was this little boy in the valley, Dick Barber (Claude and Katie’s son) who my grandfather had befriended. Grandpa Paul was a minister at the (Mennonite) church and the Barber kids would go there sometimes. Not long after Grandpa died, Dick came down with scarlet fever and died, too. The Barbers wanted their son buried next to my grandfather—and he is, in the Mountain Home Cemetery.”

Over time, progress came to the cove in the form of motorized tractors. Single- and double-tree horse harnesses were stored in the shed to become relics of another era. Just as the tailor in Anatevka was happy to buy a sewing machine and discover a modern convenience, Indian Cove residents were thrilled when telephone service finally came to their rural outpost in 1950. In Del Snyder’s memoir Growing Up in Indian Cove, he wrote about the impact of the nuclear age in the valley. Del remembered a night in 1953 when he saw the light from an atomic test blast hundreds of miles south in the Nevada desert. Similarly, Dale talked about his father gathering the family in the front yard in 1969, and pointing at the dim outline of the moon in the sky. “There,” Wes said. “The astronauts are walking up there.”

Despite such developments, the old ways and rituals that early Indian Cove settlers brought with them were not forgotten. Each day at 3 p.m., Mike Shenk would walk away from an irrigation birdie or get out of his tractor and go visit his Uncle “Kuchen” (Carl). He and his uncle would drink coffee and eat cookies. It was a tradition stemming back to the valley’s first Johnsons, who’d grown up in Sweden before coming to the cove in the early-1920s. Mike was a living example of the peaceful cohabitation and intermarriage of two distinct cultural strains in Indian Cove: his father Tim was Mennonite and Germanic, and his mother Edith was Swedish.

For many years now, I’ve enjoyed being part of this community. I’ve learned much here (for example, how to can peaches!) and even have had a few hair-raising experiences. For instance, one Sunday many years ago I went to a potluck at the church. I brought with me a covered fruit bowl that I put on the floor of the passenger side of the car. As I drove down the road, a three-foot wall of water suddenly came at me. I couldn’t believe my eyes. I later learned that a downpour south in the desert had caused a flash flood. I stopped the car and watched the water slowly rise over my tires. An indelible image in my mind is of my covered fruit bowl floating on the car floor. Eventually, my husband arrived on the tractor to rescue me.

An Indian Cove tradition that lasted until about fifteen years ago was the ladies’ coffee hour held once a month at different homes. It was finally discontinued because many of the women had begun working out of their homes and weren’t available for coffee. Cove women are wonderful homemakers and often are especially good with a needle and thread. Over the years, there have been several sewing and quilting circles. When I first met my sister-in-law, Lois Hooley, I was surprised by her many talents. She quilted and gardened but she also raised sheep and even sheared one once, in order to make a sheep skin vest. Lois got her bum (or motherless) lambs from the Wilbur Wilson sheep camp, a long-standing feature at the east end of the valley.

Today, there are fewer people in the cove than Dale recalls from the 1960s, when the school bus was full of kids: the Hooleys, the Blacks, the Hamiltons, and the Shenks. At its height in the 1950s the community had about 140 inhabitants while today there are around sixty. The population has aged and the oldtimers are dying. Many farmers, including my husband and me, are now retired and rent our farm ground. The community Fourth of July picnic is no more, although every fall, Ryan and Amy Johnson still have a big harvest party. It’s good to see neighbors and friends then, to say hello to Debbie Walters over a hot cup of apple cider, or to sit on a straw bale and talk with Neva Hamilton about her raspberry patch.

As I write this, it occurs to me that although we are fewer, some of the descendants of Indian Cove’s first settlers, the Swedish and the Mennonite people, are still here. Unlike Anatevka, this community has survived—and even has added newcomers. People live here because it’s a productive and beautiful place. Water, the gift of the Snake River, has made all the difference for Indian Cove. And I can’t ignore our big skies, the sunrises and sunsets. The words to one of the songs in Fiddler on the Roof come to mind:

Sunrise, sunset, sunrise, sunset

Swiftly fly the years,

One season following another,

Laden with happiness and tears.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only

One Response to Indian Cove—Spotlight

Ted Benoit -

at

Wonderful, fascinating story. I love Indian Cove. Thank you so very much. Ted