No products in the cart.

Dr. Squeeze Chute

A Newcomer Learns Ranch Lingo

By Bobbi Phelps

Photos Courtesy of Bobbi Phelps

In 1980, suburbanite Bobbi Phelps moved to the four-thousand-acre Wolverton family ranch in southern Idaho’s Twin Falls and Cassia Counties. Her book, Sky Ranch: Living on a Remote Ranch in Idaho (Skyhorse Publishing, 2020) gives the ranch a fictional name but is a true account of her fourteen years there. This excerpt, about the cattle operation of the principally potato-farming property, is reprinted with permission.

Want to join me while I check our cattle?” Mike asked.

“Of course,” I said, sliding into the middle of his pickup’s bench seat. Mike swung his right arm around my shoulders, and we began our drive through the foothills of the Albion Mountains.

The cattle were located deep in Cassia County and spanned the corners of Idaho, Nevada, and Utah. He went often to oversee the operation, but I only accompanied him a few times. The price of beef had steadily dropped during the previous few years, and the family decided not to continue supporting the losing enterprise. They sold their remaining cattle the following autumn.

As we drove high into the mountains, Mike told me about his family. His relatives had been farmers and ranchers for generations. His parents relocated to Idaho after years of fruit and vegetable farming in Southern California. He was only nineteen when he joined his two older brothers, Gary and Don, at Sky Ranch. Gary, a strong, barrel-chested man in his late forties, was the oldest of the three boys. He moved away from the ranch and bought a machinery franchise in Twin Falls. He had an uncanny ability to fix all things mechanical from antique tractors to WWII airplanes. Don, the middle son, joined Mike and their parents, Margaret and Merle, handling and supervising the ranch responsibilities. Don and his wife, Georgina, and their daughters, Gina Dawn and Sarah, lived in a one-story brick home, a mile east of the parents’ place.

Besides the three Wolverton families, Sky Ranch supported four other men, their wives, and their children. Terry Sherrill was the foreman, a mechanical engineer, and an overall whiz at repairing machinery. Melvin Tipton oversaw the center pivots. Mario Martinez and his cousin, Danny, were their backups. The four men maintained the many irrigating apparatuses, painted machinery, and kept miles of dirt roads relatively smooth and free from snow and floods. Mike and Don joined them during planting and harvesting and hired contract workers to weed and help with extra chores during harvest.

Mike maneuvered one of the ranch’s pale-yellow pickups toward the high pastures. He had tied a red scarf around his neck and wore an off-white cowboy hat. We passed several gates on our way up the mountains. Mike stepped out to open and shut them while I slid to the driver’s seat and drove the pickup through the wide opening. Soon we came to a cattle guard. I had never seen one and realized the object worked just like a fence. A vehicle could drive over the guard, saving the need for Mike to get out and unfasten a gate. The rancher had a depression dug in the dirt between two fence lines. Next a dozen metal bars or tubes were laid inside the recess, per-pendicular to the road. He placed them about six inches apart and painted them bright yellow or orange. If an animal tried to cross the barrier, its feet became stuck in the contraption. On the whole, the cattle knew not to attempt a crossing. It worked just as well as a gate, keeping stock from wandering from field to field.

Farming on the Wolverton family property.

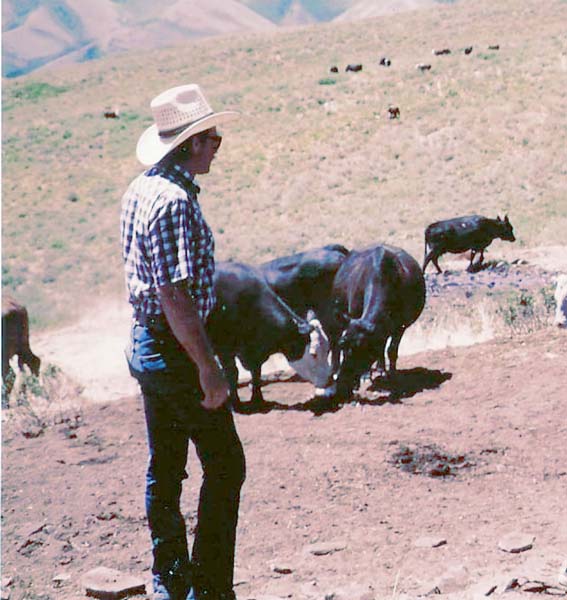

Mike Wolverton with cattle .

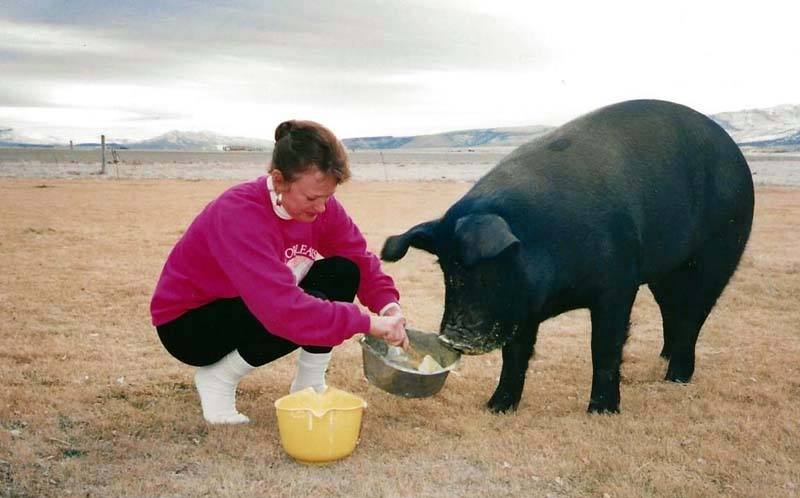

Bobbi feeds Polly.

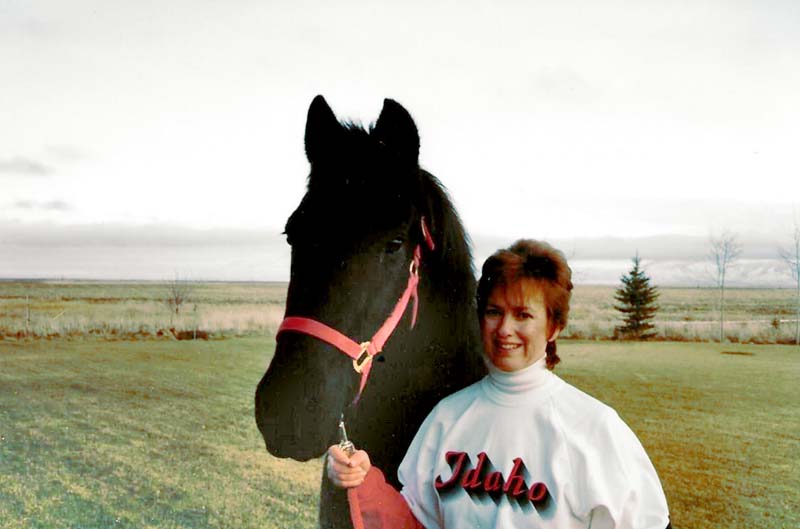

Smoky in winter.

Aerial view of the ranch.

The ranch house.

Polly the pig with minders.

The ranch in warm weather.

Bobbi with her horse Smoky.

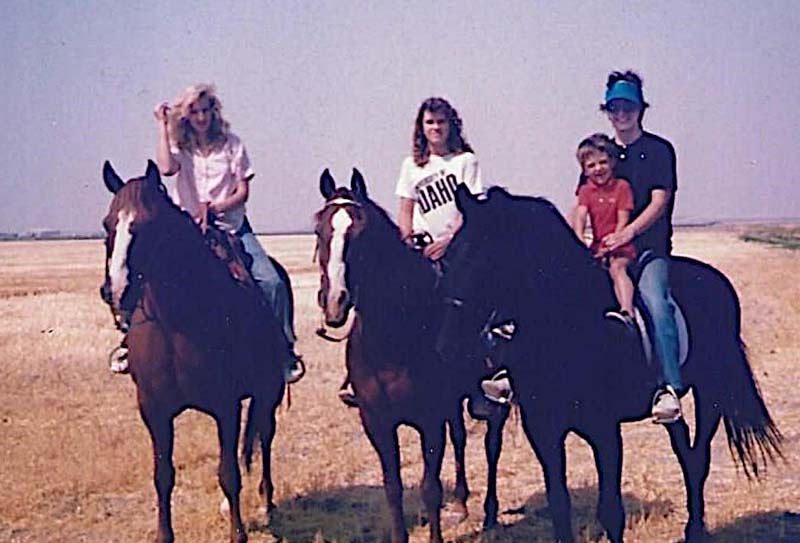

Bobbi (right) and son Matt with two of Bobbi's then-stepdaughters, Christa (left) and Gina.

At one span we came upon a Hereford bull whose foot had lodged between the metal tubes. The brown and white bovine bellowed in distress. Slobbery grass hung from his mouth as he tugged his wedged foot. There was no way Mike could get him out by himself, and his handheld Motorola radio did not work that far from the ranch. We crossed the cattle guard just inches from the angry bull.

“One of the cowboys will be checking the pasture today,” he said. “He’ll figure out what to do.” And he was right. When we returned a few hours later, the bull was gone.

The trail narrowed and shrubs brushed against the sides of the truck. At a watering trough, high in the sage-scented mountains, a group of cattle had gathered. Most were black Angus, a breed derived from Scotland, but a couple were creamy white. The Charolais, a breed originating in France, mingled with the herd. As we sat in his truck surveying the cattle, Mike told me when Charolais are bred with Angus, the offspring are not as feisty and are easier to handle.

“Angus mothers are tough protectors,” he said.

“What d’you mean?”

“I had one jump into the back of a pickup when we were doctoring her calf. Talk about panic time! When she jumped in, we instantly flew over the side rails. No way were we getting in her way!”

“What do you mean by doctoring?” I asked, smiling as I imagined the mother cow and two or three cowboys jumping in and out of the back of a pickup.

“Sometimes we’d rope a calf. And sometimes we’d put it in a squeeze chute. And if there’s one small calf, we’d pick it up and swing it into the back of a truck.”

“Then what?” I asked, so curious about all I saw. His was a lifestyle I knew nothing about, and I was interested in Mike’s answers.

“We’d take its temperature and give it a round of vaccinations.”

“What about the ear tags?” I asked, pointing to the plastic, yellow tags hanging from each cow’s ear.

“That’s a recording device. We use the tags instead of branding. See the number on each tag?” he asked.

“The one closest to us is Number 116,” I replied.

“That’s an identification number. It tells the animal’s history, its lineage, past owners, and latest inoculations. It can also help track contagious diseases,” he explained.

“Sometimes we’d accidently round up another rancher’s cow,” he continued. “With the number, we can get it back to its rightful owner.”

Mike went on to say, “Besides doctoring the calf and attaching ear tags, we’d dehorn and castrate him.”

“Wow! No wonder the animals run from cowboys,” I said as I surveyed the herd, nodding my head as I heard his answers. “So, tell me, what’s a squeeze chute?”

“Am I your own personal cowboy encyclopedia?” he teased before he continued to answer my questions. “See that green metal object to the right? It’s a portable chute. We trailered it here a few weeks ago.”

“Yeah. Then what?”

“It’s adjustable and can control the calf by squeezing its sides. And it locks the head still. With the calf inside, we can do everything without hurting ourselves or having the calf break loose,” he added.

“How do you castrate a bull?” I asked.

“A cowboy slices between the balls and uses a clamp to actually remove the testicles. He then places a special bandage over the gap. It not only closes the opening but also medicates the site.”

“Gad, that makes me sick,” I said.

“Not as sick as the bull feels,” Mike laughed. “Haven’t you heard of ‘Rocky Mountain Oysters’? That’s something Don likes.”

“Oh, no. He doesn’t eat them, does he?”

“Yup. He and some friends have a few drinks, roll them in flour, and deep fry them. He says they’re pretty good.”

“I’d need more than a few drinks to try that,” I countered. “Nope,” I amended my thought. “I couldn’t even do it with liquor.”

Confined in the truck for a few hours gave us plenty of time to share life stories. I knew he had two children from a previous marriage and that they lived with his former wife. I told him of my previous ten-year marriage and numerous funny stories of fishing around the world.

Farther down from the mountain as we bumped along the dirt and gravel road, Mike told me about the time a few years earlier when he and Lou, a hired cowboy, had trucked their horses to handle some doctoring high in the mountains. They wore leather chaps over their jeans and cotton bandanas around their necks. The chaps protected their legs from thorn and mesquite bushes. They used the bandanas to wipe sweat from their hands and faces and to cover their mouths and noses if an unexpected dust storm materialized. Surprisingly, they didn’t use them to blow their noses. Instead, they would close one nostril and blow hard, aiming the nasal material into nearby bushes. For me, that’s when the romantic image of a cowboy crossed the line. My father would have been disgusted by the practice. He always used a monogramed, Brooks Brothers handkerchief to blow his nose. Nothing less would do.

Mike continued to reminisce about his life. One time he and Lou trailered their horses but didn’t bring a squeeze chute as there were only a few calves to catch. Throughout the day, Lou continued to rope calves’ heads while Mike roped their hind feet. After each man had connected to the calf, they looped their rope several times around the saddle horn. As I learned, the men would “dally” or wrap the rope. Then their horses would back up, stretching the calf. This ensured a solid anchor as the calf had to pull against both the horse and rider.

“I’d jump off Shamrock and race to the calf, push it on its side, and wrap a short rope around its legs,” he said. Once the calf was secured, they’d proceed with doctoring.

Mike told me about riding Shamrock, his quarter horse, one particular day with his border collie stalking the strays. All day long, Lou and Mike and their horses roped and worked the calves like well-oiled machines. It was toward dusk when the unexpected happened.

Lou lassoed the last calf around its head, and it stormed out in the opposite direction. Mike kicked Shamrock and off they charged to rope the calf’s legs. Just then he heard a shriek. Mike turned back to see Lou holding up his hand. His index finger was missing.

“What happened?”

“My finger got caught in the dally. When the damn calf bolted, the rope burned off my finger.”

“Christ! Get off your horse. I’ll trailer them back,” Mike exclaimed. “You get to the hospital.”

“No. I’m not going to any damn hospital.”

And he didn’t. After loading their horses and returning to the valley, Lou went home and drank the night away. Mike checked on him later that night and again the next morning. He guessed the finger had seared shut from the rope burn and no infection had set in. Surprisingly, Lou offered to cowboy for Sky Ranch the following week, roping and doctoring as usual.

“When you move cattle from your summer grazing range, where do you take them?” I asked Mike as we continued down the mountain road.

“I’d hire a cowboy or two and round them up. We’d herd them into a cattle truck and transport them to a feed lot.”

Along the Rocky Mountain highways, I passed many silver cattle trucks, high metal eighteen-wheelers with large air holes spaced every foot or so. And when I drove from Twin Falls to the ranch, I maneuvered around the Hansen feedlot. The lot, divided into several enclosures, held only dirt and manure with nothing growing inside. Workers threw hay and a specialized growth feed into a trough alongside the edge of the pens. Tractors pushed dark soil and manure into large mounds around the barren ground. The piles looked at least four feet high with one cow invariably standing on top. “King of the castle,” I thought. While in the feedlot, the beef cattle gained weight until they left for slaughter, adding to the operator’s profit.

I continually increased my knowledge about ranching—either by listening to Mike’s explanations or by being observant as I drove around nearby communities. Once I inquired about a “female heifer.” Little did I know the word heifer is the name for a young female cow. After he laughed at my mistake, Mike told me about the birthing process.

“I’d wear a plastic glove that reached to my shoulder. It protected my shirt and gave me easy access to the womb,” he said. “First, I’d position the pregnant cow into a head gate and put on the sterile glove. With the glove on, my hand could easily slip into the birth canal.” Once inside, Mike knew if the cow needed help completing the birth. If so, he’d wrap a small metal chain around both front hooves and slowly pull, inching the calf outward. Once its hips cleared the cow, the calf would drop headfirst into the straw, covered with moisture.

“I’d clean out the calf’s nose and mouth and then dry its body with a burlap sack.”

Mike continued, “When the calf raised its head, the mother took over, licking mucus from the calf’s body and encouraging it to stand. Once it stood and began nursing, I knew everything was okay.”

Mike told me that beef ranchers describe their cattle as ‘mother cows,’ which meant the ranch had a cow and a calf. Instead of telling people how many cows Sky Ranch had, he explained, “I’d just say, a few hundred MCs. Ranchers understand.”

I absorbed cattle information like a sponge, listening to Mike’s stories, questioning him about specific items, and asking for more details. Since I was constantly curious and our relationship was still new, Mike happily obliged my interrogations. How different life on the ranch was from my youth. I had grown up in a neighborhood full of children, had animals as cuddly house pets, and swam beside sandy beaches along Long Island Sound. Nowhere had I ever experienced the broad expanse of prairie lands enclosing massive farmlands, devoid of any real population. I found the prospect of adjusting to this barren landscape appealing, even imagining my life with Mike as another great adventure. Little did I know what the future held for me.

* * * * *

On my first solo trip to Sky Ranch, I marveled at the quiet scenery. Individual farms were neatly organized in a mosaic of parcels, from orange to yellow to green and brown, like a muted kaleidoscope. Their colors scattered in the emptiness of huge fields, surrounded by a few huddled trees and bushes, planted not only as house decorations but as protection against the strong winds blowing through the valley.

After I drove across the Hansen railroad bridge, past the cutoff for Murtaugh on Highway 30, I looked for street signs. Nowhere did I see typical road designations, like Maple Drive or Smith Lane. Instead, I noticed only numbers. Mike had told me to turn right at 4900. Rural addresses in Idaho were county grid numbers, arranged by north, east, south, and west. Supposedly, if one knew the coordinates, finding the location was easy. In reality, almost everyone used visual directions. They’d say, “turn right at the green house” or “five miles past the old potato cellar.”

When I saw 4900 on a street sign, I turned right and began to notice familiar houses and barns. There weren’t many but I remembered them from previous trips to the ranch. Halfway down the street, the asphalt turned to dirt beneath my tires, a road that now resembled a waffle iron—with potholes and bumps along the way. I twisted my silver Subaru from right to left, dodging to avoid the worst of them.

While I continued on the gravel road, a large tractor came toward me. As we passed each other, I looked into the cab and saw a young boy at the wheel. He looked to be about twelve, yet he drove a huge expensive vehicle, probably transporting it from one field to another. It amazed me how farmers allowed, and even encouraged, their young boys to drive pickups and enormous farm equipment. I believed children should be more mature before permitting them to handle such huge vehicles.

On my return from visiting Mike at the ranch, I ventured into Murtaugh, a tree-shaded farming town a mile north of the highway. There were no traffic lights, no banks, and only one tiny gas station. A few commercial businesses comprised downtown: a pool hall, a small grocery store, a café, a post office, and a hardware store. The Community Building Supply store on Boyd Street reminded me of a tiny Wal-Mart. It had appliances, gifts, fishing and hunting supplies, farm goods, and hardware . . . all packed into one building. And it saved nearby residents from driving to Twin Falls if they only wanted to buy a few items.

From there I followed the old highway as it curved along the Snake River canyon. Tumbleweeds blew in front of my car and became snared in strings of barbed wire fences bordering the road. They stacked in bunches, so thick they formed a solid barrier. This was a typical sight in the blustery conditions throughout the prairie lands. The old road eventually merged into Highway 30 with the sun dipping from the sky as its last rays reached across the highway. I continued to drive west and pulled into my gravel driveway as dark dusk enveloped the land.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only