No products in the cart.

Call of the Crane

A Signal to Celebrate

By Will Roth

Photos by Linda M. Swope

I didn’t see the sandhill crane but I heard it. I was floating on the Teton River, dumbstruck by the natural beauty around me. I still am, and don’t expect that to change. Around here, when I realize my jaw has been hanging it’s because I’ve been staring at something: the Grand, or an angry cloud full of lightning, or the bull moose chewing on a willow that we passed a couple of bends upstream. It’s not often a sound invokes a feeling of awe, but for me, the call of that sandhill crane hidden somewhere in the tall grass bending in the breeze did it. Even now, whenever I hear it, I stop whatever I’m doing to listen.

It’s difficult to describe a sandhill’s call. The only word that does it justice is “prehistoric.” It carries over impossibly long distances, rolling like stones down a mountainside, echoing off canyon walls. It’s distinct, and to hear it that day on the river made me feel like I had gone back in time.

I was a visitor to Teton Valley that day. I always had appreciated nature and loved spending time in Idaho but was by no means an expert on the plants or wildlife of the region. I’m still not, and may never be, but the call of sandhill cranes is unmistakable—so distinctive that there can be no confusing it. Whenever I’m with visitors, I can say with the confidence of a seasoned guide that they’ve just heard their first sandhill. If they ask me to identify another bird’s call, I change the subject and comment on the scenery. Foolproof.

But seriously, I had learned something I would never forget, which was a welcoming experience. Being able to recognize the call made me feel as if I had something in common with local residents and with transplants who had put down roots here. There was still plenty I didn’t know, but it was a start at feeling settled.

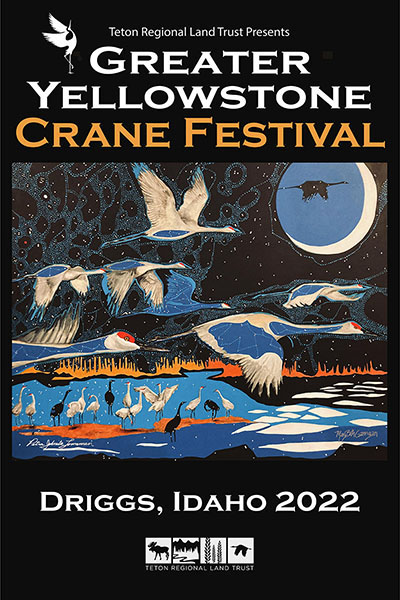

The 2022 festival poster, by MaryBeth Garrigan

and Petra Johnita Lommen.

Sandhill cranes migrate above Idaho.

Young dancers imitate cranes at the festival.

The crowd enjoys the children's dancing.

The annual art show during the festival.

A birdwatching and photography expedition.

Cranes in flight.

On the way to warmer climes.

The more floats I took on the Teton River, the more moose I saw and sandhills I heard, the more comfortable I felt. Eventually, I decided to relocate to Teton Valley, started working at the Teton Regional Land Trust, which puts on the annual Greater Yellowstone Crane Festival each September. I’ve never attended the event and had expected it to consist exclusively of informational speakers. I was surprised to discover through the people involved in it, past and present, that while the festival does have plenty of such learning opportunities, it’s really about the ways in which we are creatively inspired by cranes. Local experts lead workshops in photography, drawing, and poetry. A poster contest is held each year. Dance groups from various cultural backgrounds perform routines inspired by the cranes. “The art, the poetry, it’s all so we can relate,” I was told by Sue Tyler, the drawing workshop leader. “People want to relate to the outside world. And sadly, we’re getting less and less good at it—unless you make the effort that it takes to learn.”

Why people connect with this particular species of bird may have a different answer for everybody, but for me, it’s because they invite me to sit in silence. Of course, this could be the case with observing all wildlife in their habitat but with cranes, the silence feels more anticipatory. I’m waiting to hear that next croaking call. This gives my mind time to wander as I wait. Also, something about their size, their grace, and the relationships they have with one another inspires admiration in me. To my untrained ear, their call sounds similar when two cranes are in a field in the early morning or when just one passes by overhead, impossibly high. Yet the feelings they evoke in those instances are much different: one is a sense of contentment and ease, the other of longing and weariness.

When you’re in the presence of sandhills, waiting for a call, the silence in which you find yourself can lead to another phenomenon. Matt Daly and Ava Reynolds, who co-lead the poetry and printmaking workshop at the crane festival, discussed this recently. They said that when they think back to times of observing cranes, their lasting memories aren’t just of the birds themselves, but of the entirety of the moment. Matt told me, “I remember seeing them come in at night, seeing them gathering in a bigger group. I remember the night really well. The light on the Tetons. It’s much more about the experience than the static image of the animal. They seem almost on the verge of something: movement, or a little leap. Grace that’s almost static but not quite. Cranes are inherently beautiful, but the moment of where and when you experience them gives meaning to the place.”

In conservation work, finding ways to connect people to the cause is crucial. Kate Salomon worked to establish the crane festival with the late Joselin Matkins, who was the land trust’s executive director. She said that from the beginning, the artistic component of the festival was deeply rooted in an effort to interest a wide variety of people in a sincere way. Morning crane tours, led by members of the conservation team, also provide people with an opportunity to experience the sense of place within this landscape.

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, and particularly the Teton Basin, provide sandhills with the perfect environment in summer and fall. “During pre-migration staging, cranes are building up their resources before their long flight south,” said Tamara Sperber, Conservation Director of the Teton Regional Land Trust. “Foraging on waste grain in agricultural fields in close proximity to their wetland night roosts helps conserve the energy they’ll need during migration. Teton Basin provides that ideal alignment of resources.”

Of course, a crane doesn’t know the difference between waste grain and a crop that a farmer plans to harvest. So the land trust started the Grain for Cranes Initiative, which allows donors to sponsor an acre of farmland strategically located near prime roosting territory where barley can be grown, cut, and left for the cranes. The efforts to conserve these habitats not only benefit the cranes but also preserve the unique beauty that has drawn people here and has held families for generations: the cranes, the open spaces, the stark natural landscapes.

The ability to feel connected to the land and the changing seasons is what brought me here. At the time, I didn’t realize the role cranes would play in that. “You need to be prepared for winters here,” said Sue Tyler. “Cranes tell you when you better have your firewood in and your roof fixed. They’re a compass, in a way.” Tamara Sperber agrees. “For me, cranes are a true harbinger of fall in Teton Valley,” she told me. “It’s not really even the sight of cranes that signals a changing of the seasons for me, but their call. Hearing their calls, watching them dance, and seeing their graceful silhouettes at dusk as they fly into their night roosts give me a sense that things are right with the world.”

This month, once the sandhills flock to Teton Valley from across the Northwest, we’ll nourish ourselves alongside them, for whatever journey lies ahead.

The fifth annual Greater Yellowstone Crane Festival will be held September 12-17, 2022, in Driggs. For events and other information, visit https://tetonlandtrust.org/event/5th-annual-greater-yellowstone-crane-festival/

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only

Comments are closed.