No products in the cart.

Blamed Hard Work

What It Took to Homestead

By Rob Moore

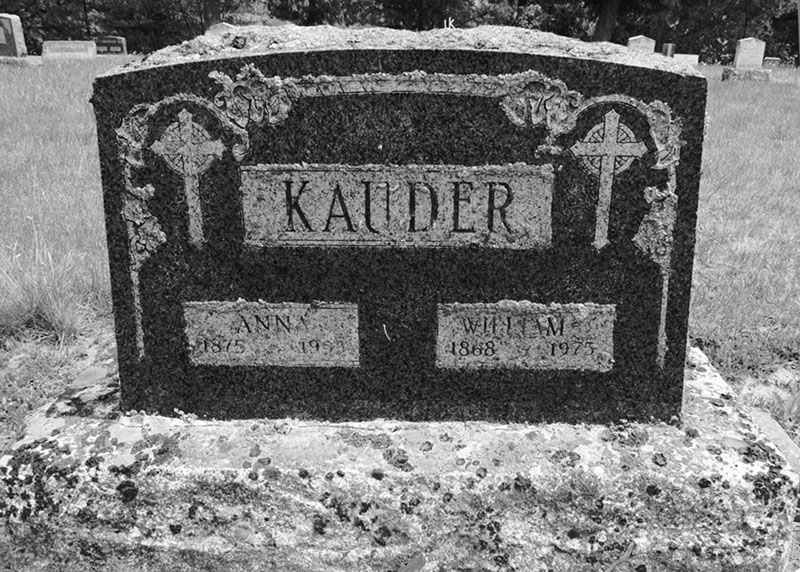

William E. “Billy” Kauder was 105 and Idaho’s oldest man when he gave the following interview to Rob Moore in 1974. Born in 1868 in Illinois, at age twenty-one he moved from Iowa with his parents to Dayton, Washington, and then to what was known as the Cedar Creek country in Latah County northeast of Southwick, where he and his father both took up homesteads. In 1918, Billy married Anna Craimer. Billy, who was a carpenter and farmer, voted in twenty presidential elections. He died in 1975 and is buried at Pine Hill Cemetery in Southwick. This transcript about his settling at Cedar Creek has been edited and rearranged for clarity. It was coordinated by the Latah County Historical Society, and the transcripts later were scanned and made fully text-searchable at the University of Idaho.

Father had an awful poor heart and the doctor told him that if he’d go West, if he’d live among the pines, that he would live ten years longer. There was only the three of us in the family, Father and myself and Mother. And we come in 1890 and he died in 1900. We come on an immigrant ticket, it was a reduced rate. Immigrant train. I think there was eighteen cars and they were all full. We bought our ticket the 17th day of March, St. Patrick’s Day, and we come West. That Nez Perce Reservation and the Camas Prairie Reservation all opened for homestead. Why they wanted them all settled up by whites is a mystery to me yet. They’d better left that with the Indians.

Father took up a homestead right in the neighborhood. It was a nice piece of land but it wasn’t much, it was only about forty acres. It laid nice and was in a nice shape. And wasn’t much brush on it. A nice piece of land but it was kind of bottled up, that is, other places was taken all around it. Father being of such a weak heart, why, we didn’t want to stick ourselves in too much of a brush patch.

We put up the [cabin] framework that fall and then it snowed us under and we couldn’t work anymore until the next spring. [That winter] there on the homestead, we put up a box house. I don’t know, it was I think sixteen feet square. Just had a fireplace in one end of it, a cook stove, and a couple of beds in there. Oh, we fared pretty good.

And then I took up a 160 [acres] not far from that. But, my gosh, it was heavily timbered. If you got any into cultivation it produced good but it was a job. There were big pines on there, great tall trees. Well, we cut down a tree, trim him up and burn the brush, saw him up in about eight, ten, twelve-foot lengths. Take a team and drag it up into log piles, and set ‘em afire. There was thousands of dollars worth of good timber burnt up just thataway. Was no sawmills around then.

Stumps, we couldn’t burn any, only the pines—they were pitchy enough to burn. Some places where there was no red firs or white firs or anything like that to fool with, just the pines, you could burn them pines out and get quite a field in a short time. Now, take across the canyon from us, over in what’s called the Gold Hill country: on that ground, principally more pines grew. They’d just burn the pine stumps out and they’d have lots of clear land in a short time. But we couldn’t do that, we had too many firs. And them first, they rooted out for, looked to be, over an acre of ground.

North of Cedar Creek is contemporary Kauder Creek. Google Maps.

The Kauders' headstone. Bailey photo.

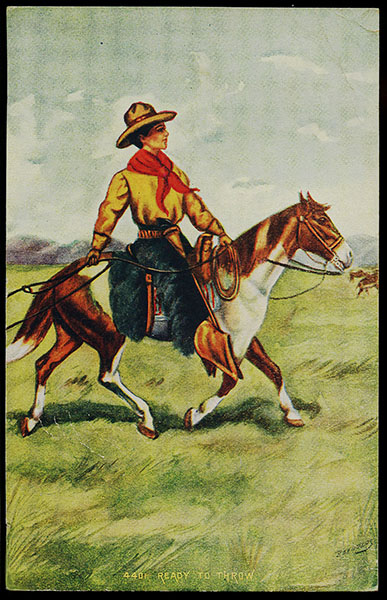

Postcard showing Southwick in 1910. Steven R. Shook Collection.

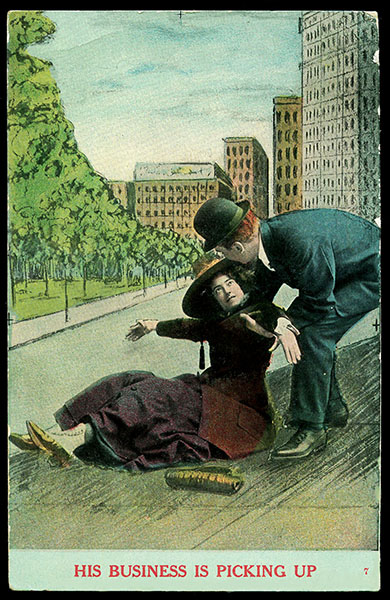

Postcard from Southwick, 1911. Steven R. Shook Collection.

William and Anna Kauder. KJ Heritage Foundation and Museum.

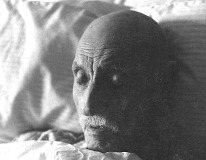

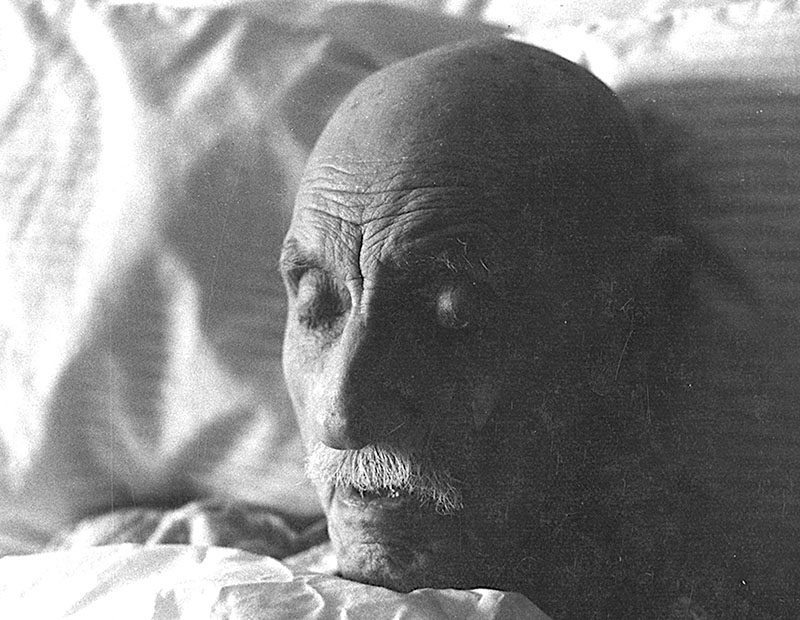

William Kauder late in life. Latah County Historical Society.

I got one of the neighbors to come over. I had five acres there that I’d cut off and I had it broke. The stumps were so darn thick on it I couldn’t do anything and the neighbor, he was quite a man with this stump powder. So I got a box of stump powder and got him to blow ‘em out. He blowed out a bunch of stumps for me, looked like I was clearing land again. My, I had a mess on the ground.

We had, I guess, four or five years before we got it so that we could help ourselves pretty good. ‘Course we got small patches in and had a pretty good garden. Raised all our vegetables. We built us a log house with three rooms in it. A living room and two bedrooms. We added on two more rooms, a kitchen and another bedroom.

I built a log house on [my acreage]. Wasn’t no lumber around. I had to build a log house and a log barn. I cleared up some land on it. And then I didn’t have it more than a year or two ‘til Father passed away. And that left Mother alone and I had to stay with Mother most of the time. And so I sold off the homestead.

Most of that [Cedar Creek] country was taken up. There was quite a big settlement in there at the time we went in. And they kept proving up and mortgaging and this [businessman] John P. Vollmer, you’ve heard of him? He’d take mortgages on all those places for backing for his bank. They’d go down to Lewiston, prove up and mortgage the place, and away they’d go. The country was well settled when we first went in there and five years later, there was just a few of us that was in there. [The others] thought they could sell out to a big price, and it didn’t prove too good.

They were good people, good neighbors. They come from different countries. The Germans, Irish, English. Some from Texas, Arkansas, Illinois. There was people from Kansas, Oklahoma, Nebraska, Iowa, Missouri, Ohio. I didn’t know a thing about my neighbor and my neighbor didn’t know a thing about me, whether I was a respectable character or not. But we never asked any questions. And we were neighbors. And all friendly one with another.

I have an idea that they [the other settlers] didn’t do so well in the East. And there was a lot of homestead land at that time [but] back East you had to buy it. When we left there, land was all the way from twenty-five to seventy-five dollars an acre. You’d get here, it’d produce just about as good as that did, only you didn’t have the market here that we had there. But then you had the same amount of land if you could crop it. But we didn’t have nothing when we come out here and we had to just take a brush claim and clear up our land.

You’d go through the woods and you might travel all day and never see anything. And all at once maybe you’d run up against a bear, something like that. But then the bear was wild and he’d give you plenty of room.

All the spare time that we could gather up, why, we worked burning out stumps or clearing up the ground. I’ll tell you, it was quite a job. We had one patch there, five acres. I had timothy in it. Timothy was way tall and heavy on the ground and we had to scythe on account of the stumps—we couldn’t get no machine in there. Then rake it up by hand. You know, that was blamed hard work. Even a small patch, like five acres, some of that was heavy enough, looked like it’d go about three tons to the acre. Gosh, you’d have to pile shock after shock. We had awful good crops them times. We growed wheat and oats.

Father and I made shingles one whole winter. We made a better kind of a building. We had a shed in front. We’d drag a log in there and saw it up in shingle lengths, sixteen inches. Then we’d split ‘em up, rive ‘em, and shave ‘em. Put ‘em up in packs. We’d get maybe two dollars a thousand for ‘em. We had to do something.

I had to work out [off the property] so much to make a living. I worked out in harvest on someone’s threshing machine, twenty or thirty days. And then sometimes in the spring of the year, as soon as I got my crop in, I took my team and I worked on the road. I got four dollars a day for that. I think I made seventy-five or a hundred dollars after I got the crop in, working on the road. I was grading the principal part of the time. And then I went out on harvest. I worked with a threshing machine and we’d get into a community and thresh that out and get into another community. That way, I kind of got acquainted with people and the country.

In the fall of the year we tried to get our supplies so we didn’t have to go in the wintertime. Because the snow where we lived would get about four feet deep and down in Kendrick it was bare ground. [Kendrick was a] pretty thriving town. I believe it was better than it is now. They had several dry-goods stores, and grocery stores, saloons, hotel. Go to the hotel and get a good meal for two bits. Beefsteak.

And then Leland sprung up. We had a good store there at Leland. We could buy just about as cheap at Leland as we could at Kendrick and we didn’t have that grade to pull coming home. That grade from Cedar Creek down to Kendrick was a holy fright. Sometimes it was so bad it took four horses to pull an empty wagon back up.

One rig wouldn’t work all the way. That’s the reason we’d take in the harvest, you know, and get enough money and get us a good supply of grub, and, as the fella says, we’d hole up in the winter. The snow got so awful deep.

We had a school, and I believe there was about twenty or twenty-five kids going. And every Friday night we had a literary. It’s kind of a debating society where they get a subject and then they’d debate on it. Some of them old ranchers are pretty good talkers on a subject. Sometimes they’d have kind of a funny question up, you know, for debate. Like, which is more essential, the dish rag or the broom? Yeah, we used to have lots of fun at them meetings. And on Sundays, why, we had Sunday School, and church when we could get a preacher but we always had a Sunday School.

Once in awhile, they had a dance. Not in our neighborhood but across over in the Gold Hill country, they’d have dances there. Once in awhile we’d have kind of what they call a play party, you know. No dancing allowed. They was kind of religiously inclined, you know, and they didn’t believe in it.

I got so important [being a centenarian] that I got a letter from President Nixon. A personal letter. Oh, he congratulated me, you know, and talked about if we had lots of such citizens, we’d have a good country. Oh, he certainly made a nice letter. One of my friends had to read the letter to me. She keeps the letter. If I had the letter here, I’d let you read it but I wouldn’t know—they laid it away for me—I wouldn’t know where it was. I couldn’t see it. Tell you, when a person is as blind as this, same as nothing. It’s the most disagreeable feeling that I’ve ever witnessed.

In some ways these changes, maybe they’re all right. But the way that it’s a’going now, I’m afraid it’s going to be trouble. Everything is getting so unmerciful high, unreasonable high. When I first landed on Cedar Creek, when Cleveland was President, you could buy a good cow for twelve dollars. Here lately I’ve heard some of them say that they got 150 dollars for a common cow.

Beef steak is out of sight. Pork, you never see any.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only