No products in the cart.

Lookout Life

Summers in the Tower

By Nancy Sule Hammond

In the St. Joe National Forest for two summers in 1972-73 and again in 2010, the author and her husband Don realized his lifelong dream of being a fire lookout. Nancy wrote memorably for this magazine about the couple’s 1970 arrival in Idaho (“Where Are the Trees?” IDAHO magazine, March 2009). The following excerpt from her new book, The Last Lookout on Dunn Peak, forthcoming in June from Basalt Books, is used with permission.

St. Maries was jammed with vacationers. It was the weekend before the Fourth of July. I waited in line to get gas. Traffic clogged the river road and kicked up a dust storm. Campgrounds were filled to capacity. RVs and pickups with campers on the back squeezed onto every wide spot on the road. A haze of pine-scented smoke from their campfires hung low over the river. I stopped at Hoyt Flat and asked Wanda to radio Don that I was on my way.

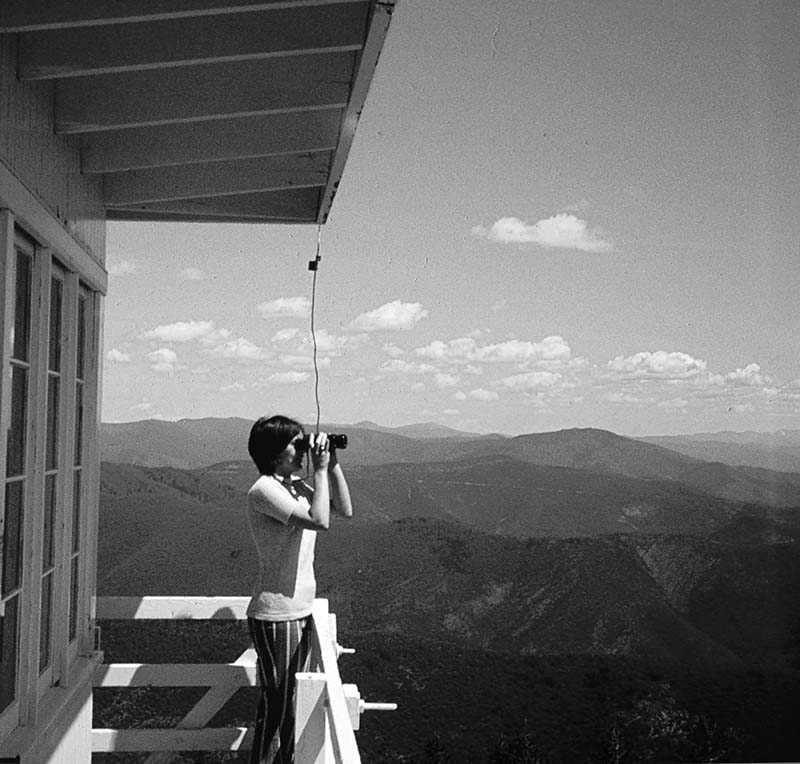

Wanda said the lookouts were on overtime because the forest was dry and campers could be careless. They threw away lit cigarettes, left camp fires unattended, and shot off illegal fireworks. The specter of the 1910 Big Burn still loomed large in the minds of the workers in the St. Joe Forest. Many had grown up hearing stories of the death and destruction witnessed by friends and relatives. People in Avery feared that the recovering forest could be reduced to ashes again. I’d thought ahead and brought binoculars from home to help Don look for “smokes.”

Past the bunkhouse I downshifted to second gear to climb the switchbacks. Our wagon shimmied in the deep dust. The engine struggled. My heart raced at the thought of tipping over the crumbling road edge. At least Don knew I was on my way. He’d radio Wanda if I didn’t arrive on time. I told myself I could handle this predicament. I shifted to first gear and told our wagon to pretend it was a Jeep. At the top of the hairpin spiral I opened my window, pulled in a deep breath of clean mountain air, smiled at my success, and shifted to third gear along the ridge.

The hours I’d driven alone on Idaho’s back roads had increased my confidence and self-reliance. I’d come to believe I could handle a challenge on my own. I didn’t want to be alone, without Don and Misty, but I was learning that I could manage. I steered around the ninety-degree curve onto the cliff-side that drops into Storm Creek. A golden eagle sat perched on the road with her talons curved over the edge. Annoyed by my intrusion, the skilled aerialist unfolded her wings full-width, released her grip, and pushed off without a single flap. She soared away on the updrafts rising from the valley and shrank to a black speck against the Idaho-blue sky. It was over in seconds. That eagle knew when she let go and spread her wings, the air would hold her up. And she could soar. Years later I’d remember her flight when I faced a major decision.

Don waved hello from the catwalk. When we’d first arrived on Dunn Peak I’d worried that Misty might be afraid to climb the lookout’s steep, see-through stairs. Silly me. Misty spotted one of the golden mantled ground squirrels that lived in the rock pile below the lookout. She charged down from the catwalk at breakneck speed, barely negotiated the turns on the landings, and flew straight past me. No matter how fast she ran, the squirrels always skittered into their burrow before she arrived. I had to wait for my hug until Misty sniffed and pawed at the rock pile to show that she knew exactly where those critters were hiding. Misty and the squirrels spent hours playing hide and seek until either she or the squirrels decided they had something better to do.

A lookout in the St. Joe National Forest, 1943. K.D. Swan, USFS.

Don chops firewood at Dunn Peak. Courtesy Nancy Sule Hammond.

Nancy and Misty at the lookout. Courtesy Nancy Sule Hammond.

Landscape near St. Maries, 1960 Peter Worr, USDA.

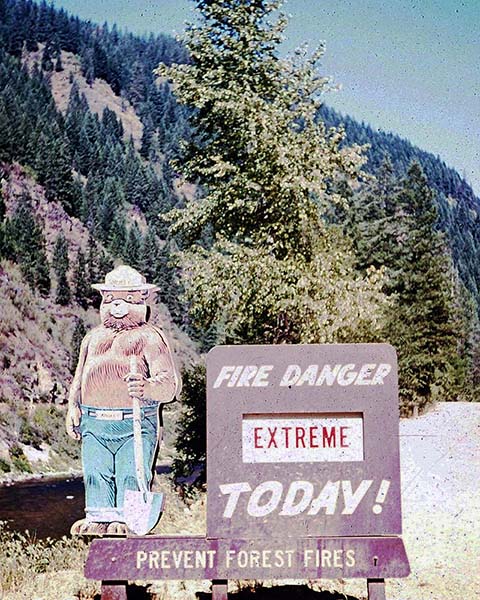

Smokey announces fire danger in St. Joe National Forest. Courtesy Nancy Sule Hammond.

Nancy watches for smoke. Courtesy Nancy Sule Hammond.

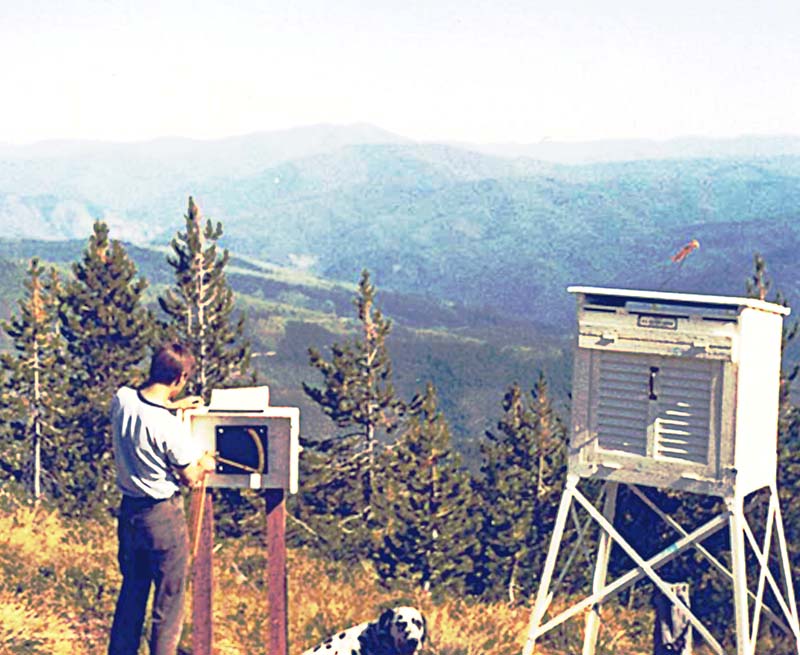

Don and Misty at the lookout weather station. Courtesy Nancy Sule Hammond.

I turned to climb the stairs and yelped in happy surprise. A fat propane tank sat strapped to the landing. Now we could cook with gas. The fire crew still supplied us with logs chain-sawed to fit the wood stove’s fire box. Don had to split the logs down to firewood. He aimed his axe blade at cracks in the log and swung hard. With two or three chops he broke the log in two. Then he’d split the halves into smaller pieces easy to burn. If the log had knots where a branch had grown out, Don pounded in a steel wedge with a sledge hammer to split it. An adage teaches that firewood warms you twice, once when you chop it and once when you burn it. Don decided that on a lookout firewood warms you a third time, when you haul it up two flights of stairs. As happy as I was to have propane to cook with, I’d come to enjoy that ugly hulk of a wood stove. Its fires kept the lookout toasty and romantic.

Lookout towers have no plumbing, so the fire crew also supplied our water. They filled six ten-gallon steel milk cans at the bunkhouse, then trucked them twelve miles to the lookout. True to what [fire crew chief] Wade had told us, his crew unloaded the cans onto the ground. Don lugged them up the two flights of stairs by himself. It was hard work. Ten gallons of water weigh 83.5 pounds. Each steel can weighed about fifteen pounds. Don hefted nearly a hundred pounds up four steps from the ground to the first landing, up twelve steps at a fifty degree angle to the second landing, up steeper steps to the hatch, through the hatch, across the catwalk, and into the cab. A pounding, rhythmic ka-thunk, ka-thunk, ka-thunk vibrated the lookout as he stopped to catch his breath after each lift. Those precious sixty gallons had to last us one week, longer if the crew became busy with fire control duties. Don had arranged the water runs for Thursday or early Friday so he could hitch a ride to shower at the bunkhouse. He usually smelled fresh when I arrived on Friday afternoon.

Don and I washed dishes and ourselves the old-fashioned way. We heated water in a pot on the stove, poured just enough into a plastic basin to get everything clean, washed with soapy water, rinsed with clean water in another basin, and then dried. We hung wet towels over the railing and laid heavy flat rocks on top to keep them from blowing off into the trees.

Water became my gauge for how personal standards can slip away on a lookout. If I arrived to find empty water cans lined on the ground, I knew the fire crew had been busy that week. That meant Don hadn’t gotten a shower. That meant we needed to conserve what water we had left to cook and wash dishes. Our personal hygiene shifted to a low priority. I discovered that if we both smelled bad, neither of us minded. Every Sunday night back in Moscow I sank into our claw-foot tub for a long hot bubble bath, whether we’d had plenty of water on the lookout or not.

White painted rocks formed the perimeter of the helispot on Dunn Peak’s flattened summit and spelled out its location on Dunn. By the 1970s helicopters had proven a valuable tool in fighting large forest fires. Pilots who had ferried soldiers to Vietnam’s combat fields now transported firefighters to battle blazes. Or they lowered a huge bucket slung below the helicopter’s belly into a river or a lake, filled it with water, and dumped the water onto a blaze. I’d have been thrilled to watch a pilot maneuver a pin-point landing on Dunn Peak’s summit, but I knew if that happened, the St. Joe Forest or Don and I faced danger.

Prominent signs featuring Smokey Bear stood along the St. Joe’s main roads. They informed forest users of the fire danger and reminded the users that they served as the first line of defense against forest fires. The National Fire Danger Rating System (NFDRS) was officially implemented that summer of 1972. The system expresses the calculated fire danger in five class levels understandable by the general public:

Low (Green) – Fires are not easily started

Moderate (Blue) – Fires start easily and

spread at a moderate rate

High (Yellow) – Fires start easily and spread at a fast rate

Very High (Orange) – Fires start easily, spread rapidly, and quickly increase in intensity

Extreme (Red) – The fire situation is explosive and can result in extensive property damage

When the fire crew had installed our propane stove, Wade walked Don down the hill to two wooden ventilated boxes on tall legs that housed a Forest Service manual weather station. Don became the St. Joe’s official weatherman. The smaller shelter housed a calibrated half-inch thick rod of Ponderosa pine attached to a scale that measured the moisture content of the forest’s fuels. In the larger shelter two thermometers measured minimum and maximum air temperatures, a battery-operated fan psychrometer and disc recorded relative humidity, and an anemometer with a mechanical counter gave the wind speed in miles per hour. On its exterior the larger shelter also supported a wind direction system and a precipitation gauge. Don radioed in his readings every day. Wade plugged the data in to the NFDRS equations and used the results to decide how best to deploy his fire control resources. His crew adjusted the fire danger levels on the Smokey Bear signs to inform the public of current conditions.

That Saturday night the lookouts’ overtime ended at 7:00 p.m. with no smokes reported. Don, Misty, and I escaped the tower for a walk. Locals had warned us it was dangerous to surprise a foraging bear. Don had his fishing knife laced onto his belt, Misty had a bell tied onto her collar, and we blew referee whistles hung on our necks to alert bears that we were coming. We’d hoped the noisy holiday crowds had chased the bears into the back country. But just to be safe, we drove out the fireroad to walk where Misty could run loose.

We reached the drop-off into Setzer Creek. The setting sun cast long shadows into the deep ravine. Misty skidded to a dead stop and let out a low growl. The hair rose along her spine. I swear I saw the shadows move. Some nights I thought I heard screams on the wind. Don read my troubled expression and asked what was wrong. I admitted that being so close to a deathtrap where firefighters had been burned alive in the Big Burn of 1910 gave me the creeps. I wondered if the spirits of those firefighters still gathered at their cook tent for dinner. Had anyone warned them to run for their lives? Could history repeat itself? Could Don and I become victims of a raging wildfire? Don said I worried too much about things that would never happen. Maybe he was right. I wanted to learn how such deadly events had come to happen at this very spot, just sixty-two years earlier.

Nancy Sule Hammond’s The Last Lookout on Dunn Peak: Fire Spotting in Idaho’s St. Joe National Forest, will be released in June 2023. It will be available through bookstores nationwide, directly from Basalt Books at 800-354-7360, or online at basaltbooks.wsu.edu.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Register & Purchase Purchase Only

Register & Purchase Purchase Only