No products in the cart.

On Thomas Creek

During a Gold Rush Revival

By Clete Edmunson

Photos Mary Edmunson Collection

John H. “Jack” Edmunson II, my Grandpa Jack, took his horse down Warren Creek throughout the spring, summer, and fall to get the meat he needed and bring it back to the cabin he shared in Warren with his wife Mary and their three little ones, all of whom were under the age of five.

During winter, when the deep mountain snows lay on Warren Meadows, the deer were miles away, on their winter range closer to the Salmon River. Grandpa Jack would strap on wooden skis to get him down Warren Creek until he ran out of snow, and then he would stick the skis in a snowbank and hike the rest of the way to where the deer were wintering.

He would shoot a deer, load it up on his packboard, haul it back up Warren Creek to his skis, strap them on, and ski back to the cabin. He was in his fifties by then, his lungs full of dust from working in the gold mines all his life.

His father, Henry Edmunson, had come to Idaho in the 1890s to work gold claims in Florence when my grandfather was six years old. Jack started in the mining industry at a young age and was a lifelong miner all over the West, including at Warren. My dad, John H. Edmunson III, started as a miner but loved being in the woods and became a logger as his life’s work, while I turned to a career in education.

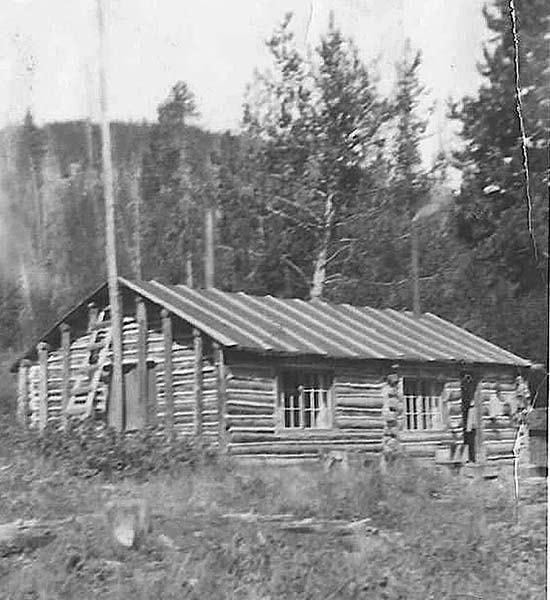

The Warren cabin of Grandpa Jack and Grandma Mary was like most log cabins built at the turn of the last century: one room with a wood stove that provided heat for winter and a place to cook meals year-round. There was no electricity, no running water, no indoor plumbing, none of the modern conveniences we have today.

A small shed built over the cooling waters of Thomas Creek was used during summer and early fall to keep meat from spoiling long enough for Mary to cook it up or can it for the winter. Jars full of deer meat, fish, and mincemeat were kept tucked away on shelves in the cellar, accessed by lifting a trap door under the kitchen floor. During the winter months, meat quarters were hung next to the cabin to freeze solid in nature’s freezer.

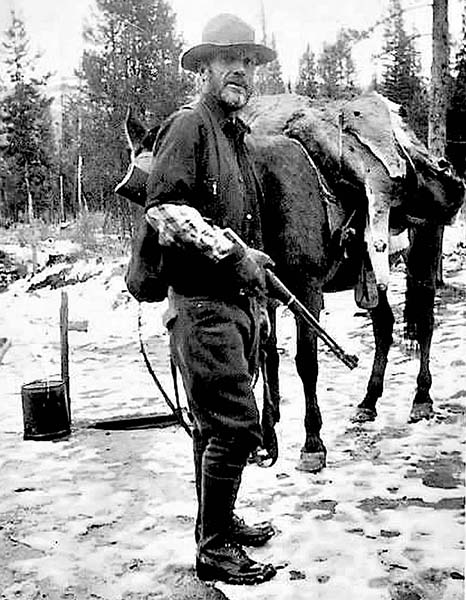

The pictures Grandma Mary left to our family tell the story of a bygone era: the rustic cabin among the lodgepole pines, children playing outside it, clothes drying on the lines. One picture shows Grandpa Jack standing beside his horse loaded with two mule deer draped over the saddle, his trusty lever-action rifle cradled in his arm. That day he had just made it back to the cabin on Thomas Creek to the welcome of Mary and the children.

The cabin was their sanctuary, far away from the madness of the world that was gripped then in the double nightmare of the Great Depression and World War II. It was nestled in the trees on the banks of Thomas Creek, one of many small creeks that flowed into Warren Creek before it found its way down to the River of No Return, the mighty Salmon.

The cabin was served by an old road that traversed Warren Meadows, wove around the then-newly formed dredge piles, and crossed Warren Creek twice before ending at the trail that led the rest of the way up Thomas Creek to the homestead. McCall, the nearest town, was a good two-hour drive away on a rough road passable only in the summer months. For much of the year, the area they had chosen to live was cut off from the rest of the world, which was just fine by them.

In a poem she called “Our Mountain Home,” Grandma Mary wrote in August 1941:

We wandered to this cabin in the mountains

To make a home where we could live in peace

And wrest a living from old mother nature,

And build anew our hopes; a vast release

From the constant dunning of the landlord,

The bills for city water, light and heat,

Unemployment and the pain of sickness,

Of wondering what the children have to eat.

We have no modern fixtures in our cabin,

We carry water from a crystal spring

And cut our winter’s wood upon the hillside,

And feel the joy that only work can bring.

There’s laughter in this little old log cabin

In spite of lamps that have a feeble glow,

And health has been restored to all the family;

It’s wonderful the way the children grow.

We have a very small productive garden,

A little pond well stocked with rainbow trout,

And on the hills are many birds and berries,

Where deer and bear and cougar stalk about.

We’ve gained a very independent spirit,

From daily work has come an honest pride,

We have a happy home in this log cabin

Here in the pine trees on the mountain side.

The cabin on Thomas Creek,1940.

Another view of the cabin, summer 1940.

The cabin in winter, 1941.

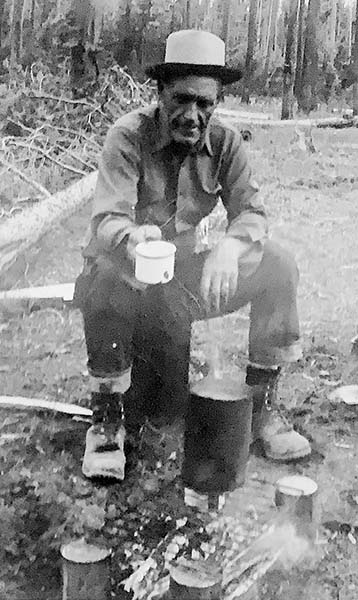

The author's Grandpa Jack with coffee from the fire.

Jack with two mule deer draped over the saddle.

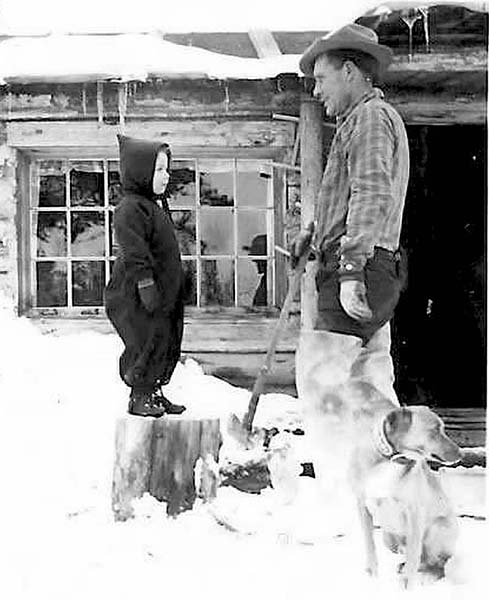

Jack and son John, 1941.

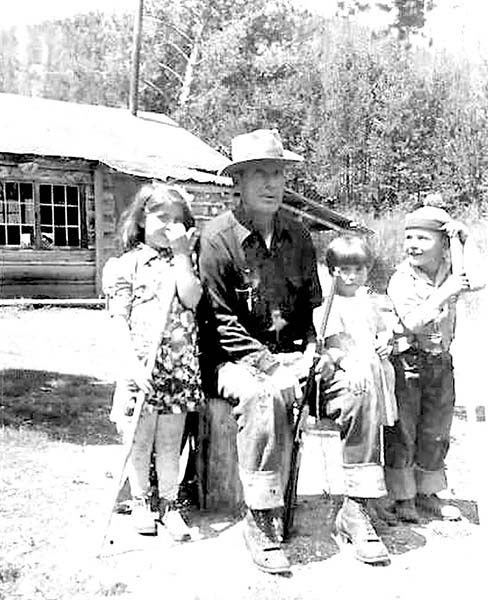

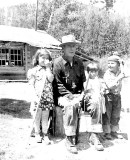

Jack with the children (from left): Tyhee, Joy, and John.

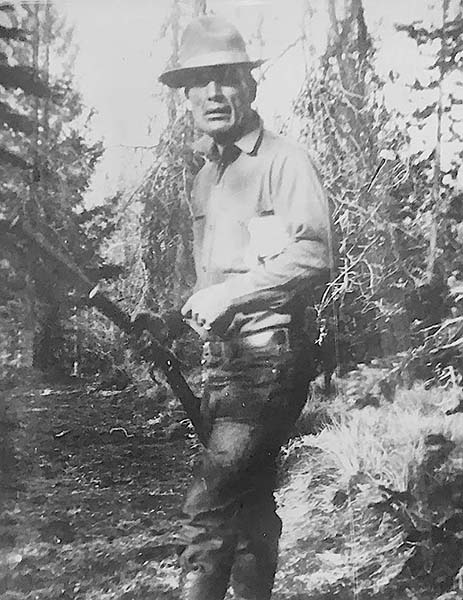

Jack with his lever-action rifle.

John, the author's father, at the cabin's ruins in 2002.

Mary holding Joy, with Tyhee and John.

The couple first met in Warren, where Grandma Mary was the cook at the hotel and Jack had returned to the area in search of work in the mines. His specialty was operating the drill deep underground, but he was open to any work. She was twenty years younger than he but despite the age difference, they fell in love quickly and were married in February 1934 in Boise.

Their life took them away from Warren as Jack followed the path of the miner, always on the move, looking for a payload. Their first child, Beatrice Evelyn or “Tyhee,” was born in the Silver Valley town of Kellogg in September 1936. Just a couple months later, Mary was expecting their second child, John, who was to become my father.

He was born in Butte in August 1937, only ten months after Tyhee. The couple’s travels took them back to McCall in 1938 where their third child, a daughter they named Burma Joy, was born.

With three kids to feed, Jack and Mary considered living in Boise but they quickly found out that it was like every other city trying to deal with the devastating effects of the Depression. Work was scarce, and the bread lines and soup kitchens provided only meager rations for families.

Plus Jack was among many people who had a predisposition against taking handouts from the government. He refused to live that way, so he picked up his family and headed back to the one place where he knew he could find work and put food on the table: the historic gold rush town of Warren.

Mary celebrated the return in her poem, “Going Home”:

The sweet scent of pine trees

On the evening breeze,

Convoyed by chickadees

Guiding me home;

Star light on timber trails,

Where a lone coyote wails,

Lamp light that never fails

Guiding me home.

Nestled beneath the peaks

Solitude my heart seeks

Majestically, God speaks

This is my home.

For the first three decades after the turn of the 20th Century there was very little mining activity in Warren, and the struggling citizens were in desperate need of good news. In spring of 1931, it came to them: the newly formed Idaho Gold Dredging Company promised to revitalize mining in the isolated community and in the rest of Idaho County. Owned by E.T. Fisher and A.F. Baumhoff, the company had purchased a dredge and was preparing to explore placer fields along Warren Meadows below town.

The dredge was to begin its work in the upper end of the meadows, and by that summer, local men already had been employed to cut cords of the local “jack pine” to be used to fuel the plant. The dredge was a steam-driven, wooden-hulled boat that sat on ponds continuously created by the dredge as it scooped up gravel in front of it. The four-cubic-foot buckets, which were closely grouped, had a daily capacity of thirty-five hundred yards.

The residents of Warren watched in amazement as the boat seemed to float in the middle of the valley floor while it gobbled up large amounts of rock. Fifteen men were employed to run the dredge. More important, fifteen families from Warren were now able to eat and live during the Depression, which everyone in the tight-knit community was glad to see.

The dredging turned Warren into one of the most prosperous communities in the state, and the rich ground kept living up to its expectations in every way. Regardless of winter conditions, dredges dug gold-bearing gravel day and night. The dredges were productive because they were steam-driven and because they worked year-round, so the ponds wouldn’t freeze over. Three shifts alternated, of three to four men per shift.

In addition to the dredging, Warren’s economic revival was aided by the U.S. government going off the gold standard in 1933, which caused the price of gold to escalate quickly. That April the set standard was $20.67 per ounce and by September gold was worth $34.06 per ounce. Warren’s historic gold mines such as the Rescue reopened, which put more men to work and further revitalized the town.

All this was why Jack knew he could find work in the mines. He also spent time cutting jack pine for the boilers on the dredges. With his crosscut saw in one hand and his double-bit axe in the other, he would walk down from his cabin on Thomas Creek to cut and pile the four-foot logs that were used to power the boiler of the Fisher and Baumhoff Dredge.

Between these jobs and a successful poker game now and then, he made enough to buy groceries and other supplies for the winter. He didn’t have to wait in bread lines or soup kitchens for handouts to feed his family. He could take care of his own.

In just four years, Warren rose to the top of the mining industry in Idaho and by the end of the decade the valleys had been overturned, with close to four million dollars in gold recovered. But just as quickly as this last boom had begun, it was over. The bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, thrust the U.S. into World War II.

Gold and silver mining in Warren came to an abrupt end when the War Production Board issued Limitation Order L-208 in October 1942, which effectively closed the nation’s gold mines. The government’s intent was to focus mining on strategic metals and minerals such as lead, zinc, copper, and tungsten that were needed for the war effort. Gold and other precious metals such as silver were deemed “non-strategic.”

The closing of gold and silver operations had a significant impact on communities like Warren that relied on them for jobs and to support local businesses. Virtually overnight, Warren was deserted. Most of the miners left for places like Stibnite, where a mine forty-four air miles northeast of Cascade was producing essential strategic minerals. The valley that had hummed with activity for the last decade fell quiet. Once again, Warren was a ghost town.

For Jack, Mary, Tyhee, John, and Joy, it was time to say goodbye to their mountain home. They spent a little fewer than five years in the cabin on Thomas Creek, yet I think it always remained home in their hearts. They loaded up the three kids and made the trek over the mountain to Cascade.

Mary worked as a nurse and the children attended school while Jack found employment at Stibnite. A few years later, they went over the mountain to Council, where they were able to purchase a small ranch and live out their remaining years.

Grandpa Jack passed away on the ranch when I was only two years old. He was seventy-eight. In a fitting tribute, my dad laid him across the saddle of his favorite horse and walked him down the trail away from the ranch to his final resting place in McCall. My Grandma Mary survived another sixteen years until 1983.

I regret now that I didn’t take the time as a youngster to sit down with Grandma Mary and ask her to tell stories and share memories of her years in Warren. I loved the tales my dad told of Warren and was inspired by the times we camped in Warren Meadows, fished in those same dredge ponds, and visited the old cabin.

I treasure the pictures from Grandma’s photo album but it wasn’t until we found her poetry that I realized how much the cabin and those years with her family meant to her. To me, her poems provide a window to a heart full of love and yearning after they left Warren for a time and place she would never have again.

A good example of that is her “Salmon River Blues”:

I’m homesick for the mountains,

I’m homesick for the hills;

I don’t like city pavements,

Or your ceaseless urge for thrills.

I can hear the blizzards blowing,

In my dreams they seem to wail;

Calling, calling me to wander,

Back along that timber trail.

Soon I’ll head back to the Salmon,

Where few white men ever go,

And live in peace with beauty

In the hills of Idaho.

Grandma’s final wish, which was fulfilled by my dad, was to have her ashes spread over their mountain home. So she finally did make it back to the cabin on Thomas Creek.

If you enjoyed this story, please consider supporting us with a SUBSCRIPTION to our print edition, delivered monthly to your doorstep.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only

2 Responses to On Thomas Creek

Penny -

at

I absolutely loved Cletes article. It brought many memories of my own to mind of family and friends. Thank you for sharing your precious memories.

Clyde M Barlow -

at

Thank you for sharing the life of your family during such difficult times the end of the Great Depression and the beginning of WW II. My parents and I moved to Idaho after the war in 1946 to the Gains place about five miles below Campbell Ferry in 1950 we bought to the Indian Creek Ranch and lived there four years. Both places had no electricity no running water unless you count the creek. I have the most wonderful memories of my early childhood we would have stayed longer but I needed schooling by nine years I had only finished one year of school so back to Indiana we went. Your article has inspired me to finish my short story for my children and grandchildren of our days in the wonderful wilderness of Idaho.