No products in the cart.

Gilmore’s Mines

High in the Lemhis

Story and Photos by Ray Brooks

When the lightly used road started looking a little soft for driving, I stopped beside the disheveled cabin of a long-ago miner. It was July 2019, and I was on a quest to visit a collection of high mines near the ghost town of Gilmore, which would complete a long list of Lemhi Range mines I had explored over the years.

The soft road induced me to get out of the SUV, because just weeks earlier I had buried it axle-deep in a mudhole on a little-used backcountry road in Nevada. Luckily, I was traveling that day with a friend in another 4WD, who pulled me out. Today I didn’t have a friend along to help. Anyway, a hike was what I really wanted.

I’ve been visiting Idaho’s high mountain mines since I was a teenager and over the decades have explored sites in the Lemhi Range, the Sawtooth Range, the Owyhee Mountains, Bitterroot Mountains, Pioneer Range, White Knob Mountains, Smoky Mountains, and White Cloud Mountains.

These searches have been greatly aided by US Geological Survey (USGS) topological maps, which usually show mine locations, and by publications of the Idaho Geological Survey and USGS. In the case of this trip, a 1997 Idaho Geological Survey publication by Victoria Mitchell on the history of mines near the ghost town of Gilmore mentioned not only the appropriately named Hilltop Mine but pointed out that more mines lay above it.

After spraying vulnerable parts of me with fly repellent, I left the SUV and hiked a first mile that went gently down and up to a creek crossing. Switchbacks then went up to the Hilltop Mine, which I managed at a steady pace. I knew the mine had been worked intermittently from the 1880s until the 1960s, but I nevertheless was surprised to see a row of sagging miners’ cabins that looked like they dated to the 1800s.

Other than a 1930s car body and a more recent water tank, I found no mining machinery or minerals of interest.

Records from 1915 to 1963 show the Hilltop Mine produced gold, silver, copper, lead, and zinc, which at current prices would be worth a total of almost $11 million. Although its early ore shipment records have been lost, the mine likely produced substantial amounts of ore from the early 1880s to 1914. Historical notes from the 1880s record large shipments of ore from the Hilltop to the smelter at Nicholia in the Birch Creek Valley.

Mindful of my research, I kept hiking up a road that now became steeper. I explored scattered mine dumps and prospect holes along the way but didn’t find any mineral specimens to take home, and finally decided to hike to a nearby high point. I had started walking at an elevation of 7,480 feet and the high point was listed on my map as 9,431 feet. For a seventy-year-old, that seemed like a good altitude to end my afternoon fitness-and-history hike.

The switchbacks on the right lead to Hilltop Mine.

Cabin ruins at Portland Mine, 9,500-foot elevation.

Hilltop Mine cabins and a large mine dump, upper left.

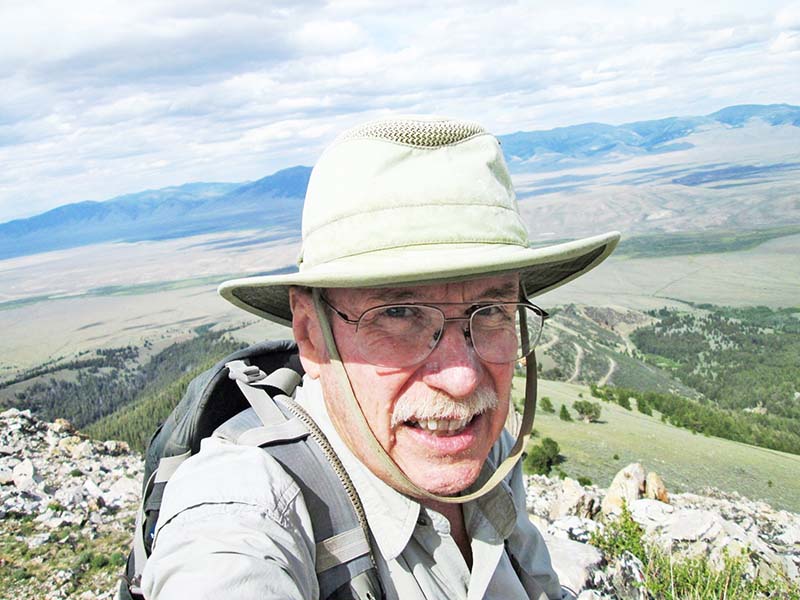

Ray on a high point above the Upper Lemhi River Valley.

Dinner table near Gilmore, 2019.

Cabin at the Mountain Boy Mine.

View of Gilmore, 2019.

Entrance to the cemetery at Gilmore.

A tunnel at the Brown Bull Mine.

The high point was composed of beautiful white Kinnikinic quartzite, a highly metamorphosed ancient sandstone that is a common formation in south-central Idaho. The view was expansive, going back down to the Hilltop Mine, then farther down to Gilmore and the upper Lemhi River Valley, then up to nearby Portland Mountain and other high peaks of the Lemhi Range.

By now, it was late afternoon and I had about four miles to hike down to my SUV before I could pitch camp and cocktail hour could begin. On my way down, I encountered a small mine where I found a nice mineral specimen of yellow-green pyromorphite (lead potassium-chloride), as a souvenir.

As I approached my vehicle, mosquitoes started to pester me and I decided it was not a good idea to camp at the edge of a swamp. A one-mile drive got me to a flat and dry spot for the night. There was no cell service but I had a way to send an “I’m OK” message to my wife Dorita.

I had been alerted to this technology back in about 2000, when I had a conversation with a man in his sixties who worked in an outdoor shop in Idaho Falls. The previous year, he had done a solo backpacking trip into the remote southwestern corner of Yellowstone National Park. One afternoon when he was ten miles from the nearest road, he suffered what he felt certain was a heart attack.

When he woke up alive the next morning, he slowly hiked out and drove to a hospital, where a doctor confirmed it had been a mild heart attack. The man strongly recommended that I purchase what is now widely known as a personal locater beacon (PLB). This small electronic device connects to satellites, which means that a user who faces an emergency even in the most remote area can send out a signal to regional 911 sites to start a rescue operation.

The PLB shows your exact location via GPS tracking. Most current models also can transmit your location and an “I’m OK” message to designated cell numbers or email addresses, and some even allow more detailed messages. They’re not cheap, but I’ve been using one for two decades.

When I’m solo hiking, I send an “I’m OK” message to Dorita at the start of each hike and repeat it when I’m in camp for the night. It gives both of us some peace of mind. I also hike with basic survival gear, a fleece jacket and rainwear, along with hiking poles that give me much greater stability on rough terrain.

Of course, I carry a quick-draw can of peppery bear spray, which reputedly is very effective at deterring aggressive bears, mountain lions, moose, and humans.

My day’s excursion hadn’t exhausted the old mines in the area, and the next morning I drove up an occasionally wet road until it became too boggy, where I parked. After about a mile of scenic hiking, I found Mountain Boy Mine near the end of the road. I followed roughly bulldozed trails above the main mine to higher tunnels at about nine thousand feet.

A few ore specimens had been left behind, there was one piece of old mining machinery I couldn’t identify, and there were a couple cabins that bore a lot of “No Trespassing—Government Property” signs. The Mountain Boy Mine was first worked in 1905 and soon became one of the larger mines in the area. Several tunnels gave access to its deposits of gold, silver, lead, copper, and zinc.

It was worked off and on until 1962. In 1988, the value of ore produced over the years by the Mountain Boy was estimated at about two hundred thousand dollars.

I returned to my vehicle, had lunch, and drove a few miles south to Gilmore. The town had boomed during the early 1900s to such an extent that a rail line built to it in 1910 was named the Gilmore & Pittsburgh Railroad. It went to the now-vanished town of Armstead, south of Dillon, Montana, where it connected to an existing Union Pacific line.

By the early 1930s, Gilmore had become a near-ghost town, but a number of historic wood-frame buildings still remain, and quite a few folks have bought lots to park their trailers on. A few historic buildings have been restored as vacation homes.

The Lemhi County Historical Society has constructed several informative signs at Gilmore about its history, and it also has preserved the onetime mercantile building. Gilmore is located just off Idaho Highway 28 from Idaho Falls to Salmon, which makes year-around access possible, even though its elevation is 7,200 feet.

My research showed that the first cabins at Gilmore were constructed in 1902, near its large lead and silver mines. Growth of Gilmore was slow, because its remote location made it expensive to ship lead and silver ore out to a railroad for processing, just as it was expensive to ship supplies in.

By the early 1900s, a large steam-powered tractor was hauling lead and silver ore from Gilmore mines on a three-day trip to the railroad at Dubois, north of Idaho Falls. Unfortunately, after only a few trips, the tractor’s ore wagons fell to pieces. Until the Gilmore & Pittsburgh Railroad reached town, most of the buildings in Gilmore were clustered around the mine sites, which were one-third mile west of where most of the structures now remain at Gilmore.

The town then grew around the new railroad station to about one thousand people during the 1920s. Yet by the early 1930s, the mines mostly shut down and Gilmore gradually became a ghost town.

Most of the large mines just west of the town are marked with “No Trespassing” signs but some aren’t, and I walked around several of them. I then drove up to scenic Meadow Lake, a few miles to the west, in search of the Meadow Lake Mine.

It remained elusive, but I stopped at the nice campground on the beautiful alpine lake and shivered in winds of 20-30 mph and 50-degree temperature. The numerous campers did not appear to be enjoying themselves.

On the way back towards Gilmore, I found the somewhat hidden but nicely maintained Gilmore Pioneer Cemetery. It rests amid trees on a limestone ridge one-half mile west of town. The cemetery has been cared for and has a nice historical marker and quite a few gravestones.

It’s a scenic site, yet with so much open terrain just east of Gilmore, it seemed to me a strange place for a cemetery, because each grave would have been drilled and then blasted out of limestone rock.

I drove south on Highway 28 to the desert that surrounds Birch Creek. The wind there kept biting bugs away but also made fishing the creek difficult. This was OK with me, though, since I could start cocktail hour at 5 pm instead of 7 pm. After sleeping in, I fished for a couple hours the next morning, but never saw a trout larger than ten inches.

On the drive home to the Hagerman Valley, I felt that I hadn’t completed my survey of high mines around Gilmore, and in July 2020, I returned to the Hilltop Mine. On this trip the road was dry, and I beat my narrow 4WD SUV up the steep and rough but otherwise decent road and switchbacks to the mine, which is at about 8,500 feet in elevation.

Aside from the fascinating row of miners’ cabins just below the mine and a fine view, I again found not much else of interest and in late afternoon I hiked toward the small mines and prospect holes above the Hilltop. Like most large mines in Idaho, the Hilltop is a patented mining claim and is private property. Thankfully, the owners allow folks to visit, but visitors should leave the property intact.

After dinner, I amused myself with the great views, and to my surprise, saw and heard an Air Force fighter jet zipping up the valley, fifteen hundred feet below me and a couple of miles away.

The eastern horizon was low over the Bitterroot Mountains and by 8:30 the next morning, I was walking. The dirt track road above the Hilltop Mine is often steep and generally narrow.

It is not a place for full-sized 4WD vehicles, but it makes for aerobic and scenic hiking. After about nine hundred vertical feet in little more than a mile, I found two old collapsed miners’ cabins and a couple of roads that led north to portals of the Brown Bull Mine group. Its recorded production was from 1903 to 1917, but based on decades of studying mining artifacts, I deduced that the rusty cans and broken glass in the old dump below the cabins indicated the mines likely were first worked in the 1880s.

Like the Hilltop Mine, the Brown Bull Mine produced ore that was rich in galena (or lead sulfide) and silver, with a little gold. It was not a big producer. The only recorded ore shipment, a single carload in 1917, was valued at $150 per ton.

After hiking a quarter-mile to inspect the outside of an old tunnel in the mountainside for the Brown Bull Mine, I returned to the ruined cabins and followed a still rougher track up to the scenic Portland Mine, at 9,500 feet. A large cabin just below the Portland Mine is positioned a short way below a good-sized mine dump, and another old cabin is on top of the dump.

The mine once had a single sixteen-hundred-foot-long tunnel to explore for valuable minerals along the contact zone of intrusive granodiorite and white Kinnikinic quartzite. The Portland Mine had recorded production of only about fifty tons of ore in 1910, which contained forty percent lead and two hundred ounces of silver per ton.

Although the alluring nearby summit of 10,820-foot Portland Mountain beckoned, it looked like a long slog up slopes of loose rock. I started back down, but a side road near the Brown Bull Mine cabins that I had not explored lured me along it. At the end of the road, I found a newer cabin that had been repossessed by the Forest Service.

Notices nailed on the door and on the boarded windows identified it as U.S. government property. I visited one more nearby old mine dump that held an interesting ten-foot-long compressed air tank made of riveted iron. It would have provided compressed air for drilling into the rock to set dynamite charges.

By now it was noon, and the high-altitude biting flies were starting to annoy me. I retreated back down to my SUV at the Hilltop. Happily, I had the rough and narrow road to Gilmore all to myself, except for some fresh cow droppings. From there, I once again drove south to the hot and dry desert along Birch Creek, where flies and mosquitoes were few, to car camp and do a little fishing.

I had achieved my goal: I could not think of more Gilmore area high mines I wished to explore. But of course that wasn’t the end of my list. There are still more mountain mines left on it.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Register & Purchase Purchase Only

Register & Purchase Purchase Only