No products in the cart.

Worley–Spotlight

A Childhood Home, Decades Later

By Sue Ellis

Worley, population 257, doesn’t much resemble the bustling little community I knew as a kid. Located within the boundaries of the Coeur d’Alene Reservation, the white population surpasses the native one because of the Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909. The act targeted land suitable for dryland farming and opened the lands of three Northwest tribes to a lottery. Eighty percent of the Coeur d’Alene Tribe’s holdings passed out of its ownership during that time, and into the hands of homesteaders whose winning tickets entitled them to file a 160 or 320-acre claim.

Worley is twenty-seven miles south of Coeur d’Alene, but Lake Coeur d’Alene connects with Worley’s sandy beaches just six miles northeast of town. Part of the lake’s shoreline is included in the town’s delivery zip code. My dad, Joe Wright, told me about winters long ago when people would drive their cars across the frozen lake to Harrison.

In 1936, my maternal grandparents, Clair and Ida Sheldon, moved to Worley, eventually settling along the winding, dusty road that led to Bloomsburg Landing on the lake. Clair had served in World War I, and he later met Ida at a Kansas boarding house where she worked. Her first husband, Jesse Morlan, had been killed in an accident, and she supported her six children alone. My mother, Nellie, was only five when Grandma and Grandpa got married in 1925, but the older kids remembered holding a lantern after dark so their mother could see to pin the boarders’ laundry to a clothesline.

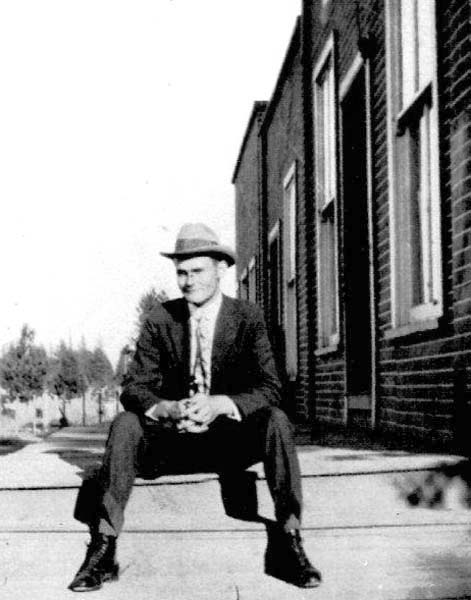

When they moved to Worley, Grandpa was employed by the Works Projects Administration (WPA), a federal agency that was charged between 1935 to 1943 with instituting and administering public works aimed at reducing national unemployment. Grandpa owned a delivery truck, so his initial assignment in weed extermination soon expanded to giving lifts to fellow employees, and then keeping track of their work hours for the payroll office. He eventually began delivering government commodities as well, such as fresh fruit and wool quilts made from surplus army blankets. Former Worley resident Mike Cronk told me he remembers tasting a banana and an orange for the first time from one of Grandpa’s deliveries.

Grandma was a fine cook, although her dark fudge always went to sugar. More often than not there was a pot of lima beans and ham simmering on the stove for unexpected company. She played the mandolin and sang breathless songs punctuated by laughter. My grandparents moved to the farm on the lake road in 1948, the same year I was born. By then they were stoop-shouldered from years of leaning into a task, and their faces were creased like roadmaps to kindness. They epitomized what I remember about Worley families in those days.

Back in the early 20th Century, when the federal government sold tribal grounds to white settlers, it promised the tribes funds for schooling and medical care. As we now know, the release of the land led to increased heartache for the tribes, and lawsuits continue to this day regarding the policies of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Meanwhile, people of diverse ancestry put down roots alongside those of the tribes, and people managed to coexist peacefully and to work together in what was to become a bustling agricultural community.

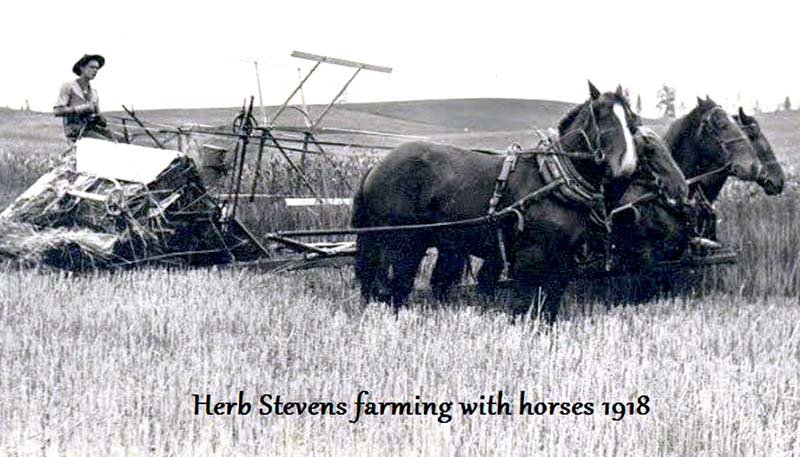

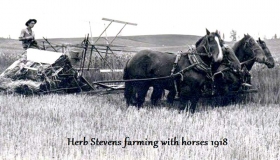

A few Coeur d’Alene Tribe families mastered the unfamiliar concept of dryland farming and produced cash crops from their own allotments, and many more hired on as farm hands, helping to plant and harvest the wheat, peas, barley, and oats that were staple crops at the time. Still others chose to lease their allotments to newcomers for a share of the crop yield, a practice that had begun even before the Homestead Act came into being. In 1907, two enterprising brothers from Fairfield began farming a few miles north of present-day Worley.

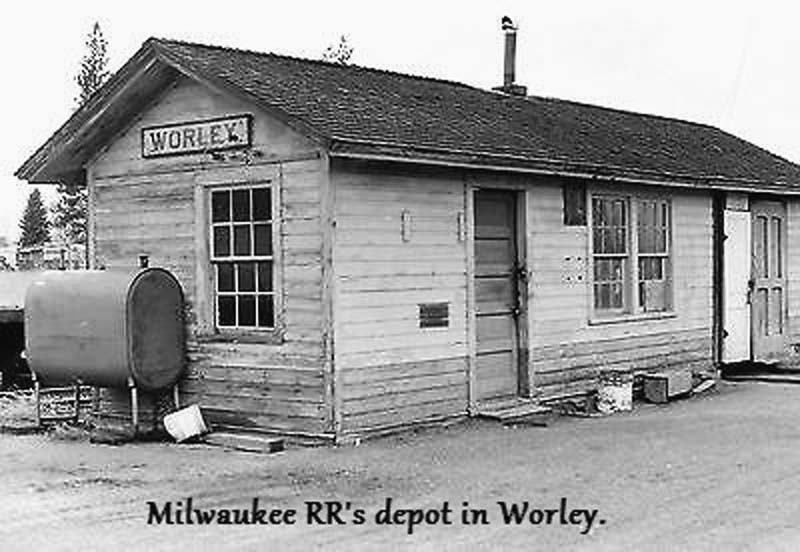

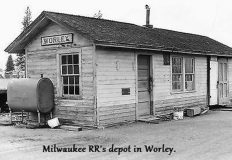

Named after the area’s first Indian agent, Charles Worley, the town’s main street boasted a store by 1907. Dorothy Dahlgren, director of the Museum of North Idaho, researched the history of Worley’s railroad for me, and I learned that the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul, and Pacific Railroad (also known as the Milwaukee Road) was about to lay track through that area at the time. It seems probable that the Pioneer Store’s owner, Martin Walser, was, as the old expression goes, “betting on the come.” At first, Walser traded with the tribes, accepting beadwork as payment. Later he welcomed railroad workers and homesteaders. Worley eventually had its own depot on a route that ran between Spokane, Washington, and Superior, Montana. Residents could buy a round-trip ticket to Spokane in the morning and return by suppertime. Passenger service continued on the railroad until 1953.

When Worley was platted in 1908, Main Street was drawn with generous lots to accommodate business activity, but then in the 1920s Highway 95 cut through town, one block south of Main Street. Its location prompted Jim Mottern to relocate his store to the busier thoroughfare, and others followed suit. The willingness of early settlers to roll with the tide makes it easy to imagine time-lapse images of structures rising up, falling down, or relocating as the 20th Century unfolded. Worley became incorporated as a village in 1917, and elected its first mayor, Ernest Lagow, when it became a city in 1956.

After President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed legislation establishing the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), Worley hosted Camp Peone, just east of town. Established in 1936, it served as school and home base for CCC recruits from Arkansas, Missouri, and Illinois. The town’s water tower, which still stands, was built by men from Camp Peone. The training and assignments of the two hundred recruits were overseen by the Soil Conservation Service (SCS), which is why Peone was also known as Camp SCS-2. The projects, covering more than eighty-five thousand acres in Idaho and Washington, included grading land and constructing dams and checks to control gullies, and involved a great deal of cement work. According to some accounts, Worley’s young, single men didn’t much appreciate the new competition, which may help to explain the high incidence of bare-knuckle boxing matches that apparently took place.

After Camp Peone served its purpose and closed, the wood-framed buildings that made up the compound were salvaged by Worley residents, who wisely took heed of Depression-era advice: use it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without. Tom Wolf bought a new tractor about that time, and volunteered to move one of the wood-framed buildings into the heart of Worley to serve as the new community church. Del Breeden bought several buildings and moved them into town to remodel as rentals. Wid Parsons used salvaged lumber for his new hotel. Brick by brick or, in this case, two-by-four by two-by-four, the town assembled and re-assembled with the changing times.

Camp Easter Seal opened in 1950 on lakefront property acquired by Washington State University. It served for more than fifty summers as a getaway for handicapped children to enjoy a camp experience, and as a field school for WSU education students. The thirty-six-acre compound changed its name to Camp Roger C. Larson in the 1980s, honoring the founding director of the university’s college of education faculty. The camp closed in 2003, and the following year the Coeur d’Alene Tribe bought the camp back. It now serves as a serene setting for native studies and recreation.

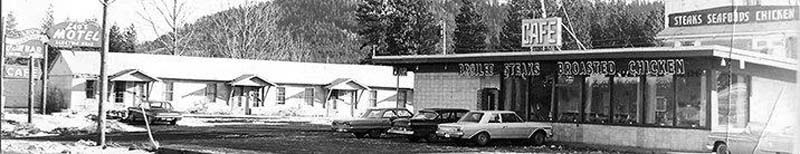

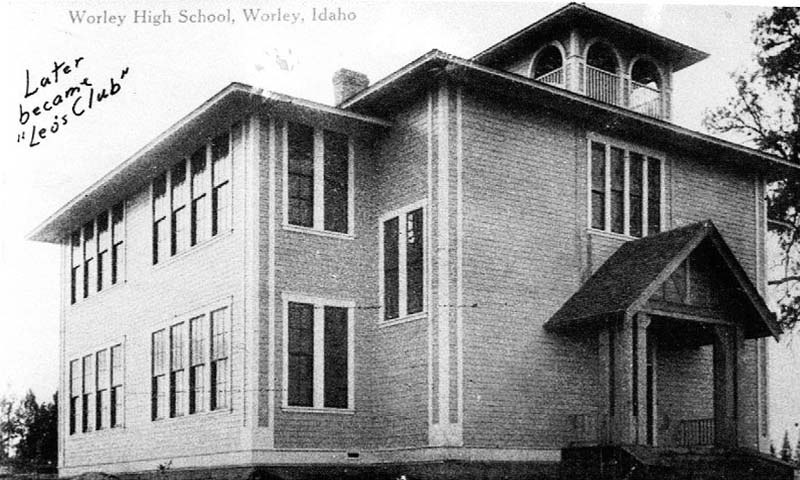

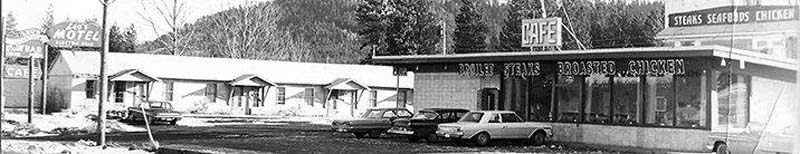

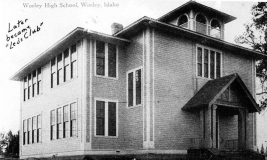

The high school where my dad graduated, which was built in 1925, was an attractive structure at one time, but in the 1950s, Leo Fleming attached a low-slung, period diner to the two-story school’s clapboard face. Electric lights flashing along a long pole pierced the night sky, and the first floor of the old school was transformed into dining and dancing space. Leo’s Worley Club drew customers from as far away as Spokane for its Saturday night smorgasbord, and kept up the momentum for decades.

I remember Dad taking me into Leo’s around 1952, when I was almost five. He hoisted me up to the polished bar and asked the bartender to let me shake the dice for a candy bar. Miraculously, I won a boxful of spoils that probably kept my younger brothers and me wound up well past bedtime. The town’s blacksmith at the time was Ralph Lovejoy, whose name Dad fondly prefaced with the word “little,” leading me to believe that all little people were good. He was indispensable, forging tractor parts as easily as horseshoes. Lagow’s, one of two tiny markets, had a walk-in freezer where space was rented to families who didn’t have enough space at home, and where a kid like me could cool off on a summer’s day while her mother rummaged for what she needed. A restaurant moved into what had previously been the first floor of Wid Parson’s old hotel. Thompson’s Cafe was a place where a young man could fall in love with the chicken-fried steak and the pretty cook. At one time, Worley had a drugstore, dry goods, hardware stores, auto dealership, vehicle repair, a co-op supply store, and boardwalks.

Worley even had its own rodeo for a while. Begun by the local Lions Club in 1948, it was headlined as “Five Days of Western Fun” in a June 1950 newspaper story in the Spokesman Review. It began with the three-day encampment and powwow of the Coeur d’Alene Tribe, followed by the town’s “first” rodeo on July 3 and 4. Evidently, the 1950 rodeo was advertised as the first one because of its new location at the town’s old baseball field. The amateur rodeo drew large crowds and talented cowboys from across the country. And there was no shortage of local beauty to appoint as rodeo royalty for the parade that preceded the event.

Worley’s small boom lasted for decades, but slowly the old ways of life eroded. Farming began to require more and more land to make the same profit. These days, conventional wisdom says that farms must either get big or get out. Although crop production continues, it requires less manpower than it did in the old days, because big tractors and big corporations streamline the job. The sprawling, tribal Coeur d’Alene Casino with its golf course, convenience store, gas pumps, and lodging is currently the area’s largest employer. The many businesses that lined Worley’s main street are dramatically fewer than they used to be, unable to complete with the nearby casino or the lure of better bargains within a forty-minute drive to either Coeur d’Alene or Spokane. Worley is still a viable community, but it no longer has the variety of businesses that made the town self-sufficient in bygone days.

A census chart for Worley shows that the 1920 count was 186, which rose steadily over the following decades to 241 in the 1960s. The numbers declined to 182 in 1990 before rebounding to 257 in 2010. Tourism at the casino seems to have surpassed the employment opportunities that farming once provided. The Coeur d’Alene Tribe’s website says the casino employs fifteen hundred to two thousand workers, depending on the season.

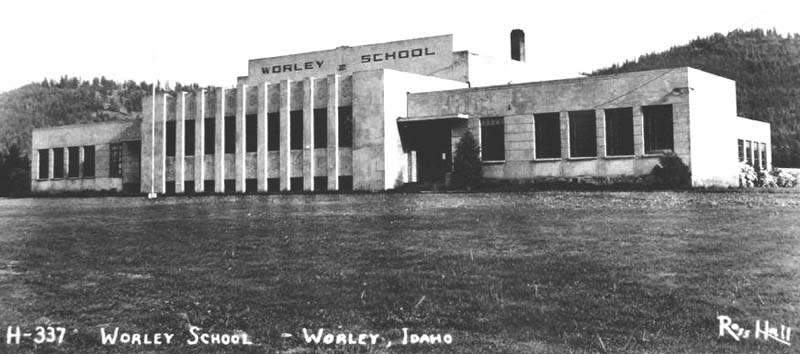

I recently attended my Uncle Bud Sheldon’s eightieth birthday celebration at the Worley Grange Hall. My family moved away from the area in the late 1950s, and although I hadn’t been back in a while, I’d read about the efforts of several local people to save the town’s old concrete school from the wrecking ball and turn it into a historic site. The school was built in 1939 for grades one through twelve, but had been vacant since 1987, when the school district began busing Worley’s students to Plummer, six miles southeast. A follow-up story some months later reported that the school district voted to go ahead with demolition.

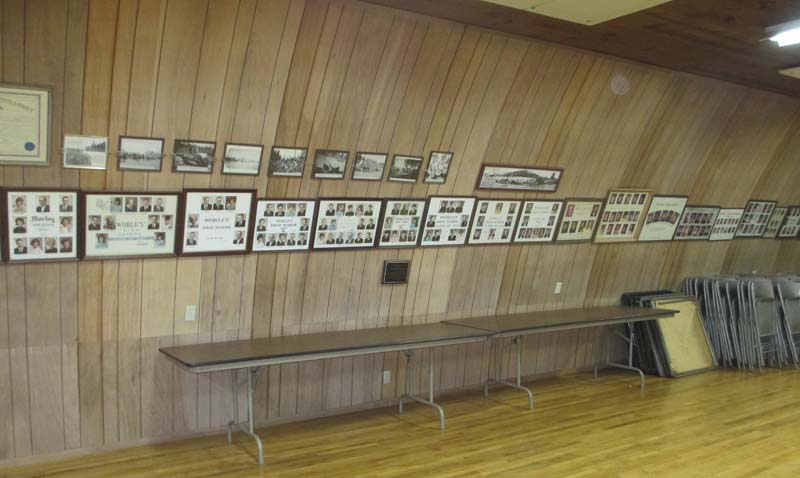

The Worley Grange Hall is a Quonset hut-style building, erected in 1959 after the original building burned to the ground. Built with lumber from a donated tree (eight feet across at the base) and donated labor, it’s one of the few remaining holdouts that hearken back to the area’s homesteading roots. The building is windowless and uninviting from the outside, but the paneled walls inside gleam in the artificial light, and marching in single file down the two long side walls are the rescued photos of every graduating class from the recently demolished school, as well as graduation photos transferred there from Worley’s old high school.

In a far corner, where a flickering propane stove entices visitors to explore the room’s cave-like depths, the class photo of 1931 leads off the chronological procession of fifty-five classes, each relegated to an orderly history by its place on the wall. The photos were rescued by my aunt, former-resident Darlene Sheldon, a retired school teacher and civic-minded history buff who lived in Worley most of her life. Her vivid memories were of great assistance to me in writing this story.

In the class photo of 1935, I found the boyish face of my dad, and in the same frame, the equally handsome portrait of Elmer Whitman, a family friend whose memories of old Worley strike me as phenomenal. Names I’d heard my parents speak came to life in the black-and-white images, and as I moved around the room, I discovered that a few of them had children who were also Worley graduates, and grandchildren as well. I recognized more people than I thought I would, and felt more at home than I could have imagined.

I spent the better part of an hour searching through each frame for familiar faces and trying to match world events with the dates on the photos. I found old classmates with whom I’d have graduated if my family had stayed, easily reconciling eighteen-year-old faces with the third-graders I’d left behind more than a half-century earlier. There was the expected assortment of farmers and loggers intermingled with a math professor, a traveling piano salesman, and a novelist. One young man wore his U.S. Coast Guard uniform. Out of all the old buildings that used to front Worley’s main street, only the grange has survived intact, continuing to serve as it always has, for the benefit of local people.

Rise and Decline of the Grange

The Grange is a fraternal organization whose roots go back to 1867. The brainchild of Oliver Kelley, it was created at the urging of President Andrew Johnson as a means of bringing people of the southern and northern states back together after the Civil War. It succeeded. A lot of good was accomplished by the cooperation of dues-paying members over the years. The Grange lobbied for “rural free delivery,” which became a reality when free mail service to rural families began on July 1, 1902. The organization also worked to achieve railroad regulations that prevented transportation costs from skyrocketing for struggling farmers, supported the temperance movement, and encouraged the participation of women in the Grange, an enlightened policy in that era. Over time, its community buildings evolved into places for social functions as well. But in the last fifteen years, grange membership has declined by forty percent.

As I left the Worley Grange building after my recent visit there, I wondered how much longer it would survive, both for its intended purpose and as a repository of the town’s history. It seems to be changing with the needs of the people, as granges nationwide have traditionally done. The Worley Grange currently serves as a meeting place for a small group of grangers and for members of Worley’s historical society, who contributed photos and historical facts for this story.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Register & Purchase Purchase Only

Register & Purchase Purchase Only

2 Responses to Worley–Spotlight

Marcus -

at

I have some questions about the history of worley is there anyone you can point me in the direction to? Thanks

Deandra Allor -

at

Aw, i thought this was a really nice post. In thought I have to put in writing this way additionally – taking time and actual effort to create a top notch article… but what / things I say… I procrastinate alot by no indicates seem to get something accomplished.