No products in the cart.

Those Bleeping Sheep

Shortly after World War II, strange things began happening in the northern Idaho woods where I was raised. Each spring, bands of sheep began showing up in our logging community of Headquarters, deep in the Clearwater National Forest.

They temporarily blocked traffic on the roads and we occasionally ran into flocks in the mountain meadows while riding our horses. We grumbled, “Who in bleep would bring all those sheep out in the woods and turn ‘em loose with all our wild animals? Why, they’ll just eat up all the grass, and our deer and elk won’t have anything left to eat. They’ll bleep in our cricks, kill all the fish and besides that, they stink!”

Backwoods sentiment on the subject ran rampant. Of course, as a young buck I got sucked into the local opinion against the sheep. At the time, we had no idea that permission had been granted by the Clearwater Timber Protective Association in Orofino to bring in the flocks for summer grazing.

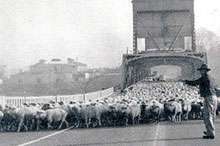

One day, while riding through the woods on my horse Ribbons, I came upon a meadow full of sheep. The sheepherder was congenial and invited me to sit and talk awhile. He explained how he and the dogs took care of the sheep out in the woods. Years later, I learned these particular sheep belonged to Hi Hood, a rancher who had shipped bands of sheep on the Camas Prairie Railroad up through Orofino Creek to the Hollywood Stock Pens near Pierce. There, they were divided into smaller bands and driven with the aid of sheep dogs into the surrounding meadows. The sheep were kept moving so as to not strip all the vegetation and were kept away from the streams except to drink. Continue reading →

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only