No products in the cart.

Pioneers of Tailgating

On September 30, 1950, I was an eight-year-old University of Idaho football junkie, living in Lewiston, bleeding, bleeding Vandal silver and gold. September 30 was to be my day. There would be no bleeding whatsoever, only excitement. Five days earlier, Mom had told me I would be going with my father Stan to my first college game. Dad usually went with Bill, Curly, or Louie—sometimes all of them, sometimes only one or two—but today it was just me.

Television had not yet arrived in the Idaho Panhandle, so I listened to every Vandal game on the radio, and the next morning I read the recap in the Sunday paper. Bob Curtis was the voice of the Vandals, who I figured had announced and would announce every one of the team’s football games from the beginning of time until the end of the world. Through him I knew the Vandal colors, their fight song, their record, who coached, who played where and when. On this day, Idaho was to play Montana State University, a team we were on even terms with. Back then, the Vandals were members of the old Pacific Coast Conference. They played a full schedule in basketball, but in football they played only the teams from the Northwest, the two Washington schools and the two Oregon schools. Winning against the conference schools was tough to do, and I bled plenty, but against the Montana schools the odds were about fifty-fifty.

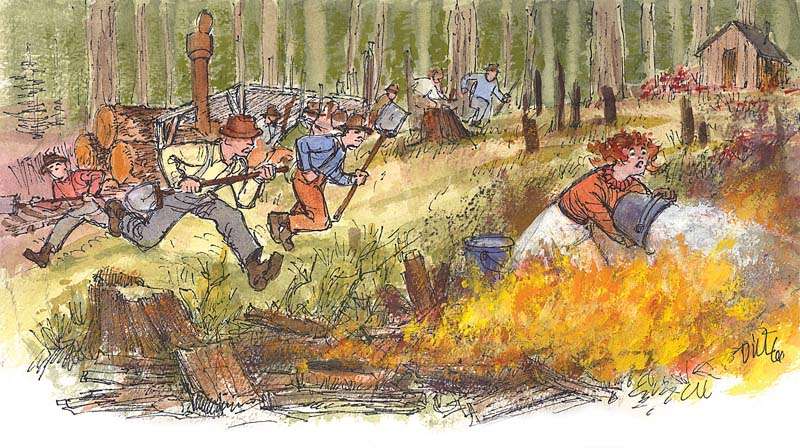

Mom spent most of Friday preparing food for Saturday. Southern fried chicken topped the menu, cooked the way only Mom knew, dipped in bread crumbs, flour, and egg, and then slowly fried and seasoned as the day moved along. At our house, fried chicken was always served with potato salad made of Idaho russets, free-range eggs, mayo, onion, greens, olives, pickles, and a dash of mustard. I knew this was where the phrase, “finger lickin’ good” must have originated. We ate plenty on Friday night, when the chicken was still warm. Early Saturday morning, Mom filled the cooler with ice, chicken, potato salad, beer, soft drinks, potato chips, dip, chocolate chip cookies, and some candy. And then it was nine o’clock. Continue reading →

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only