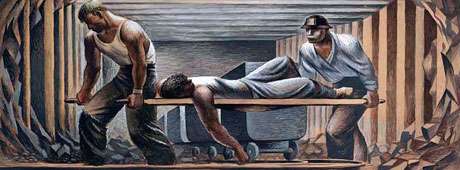

When my family took a trip across the northern part of the country recently, we made many stops in Idaho. I had a special reason for doing this. As a history student at the University of Southern California and a research associate of U.C. Berkeley’s Living New Deal Project, I help to gather data and materials about President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s promise of a “New Deal” for America during the Great Depression. And the deal Idaho received at that time was unparalled in the nation. Despite ranking forty-second in population, the state ranked eighth in federal spending during the Depression. More than two hundred new buildings were constructed, including dozens of schools, courthouses, and post offices. National and state parks were improved, and countless miles of roads, sewers, and runways were added throughout the state. Over the course of just a couple of years, Idaho was transformed.

I wanted to find out what remains today. I wanted to know if it was possible to trace the legacy of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) throughout Idaho, and such questions filled my mind as my parents, my sister, and I drove across through the state. To me, the memory of the WPA is even more poignant because next year is the eightieth anniversary of the program’s start. My quest in Idaho was to chronicle the WPA’s history here—trying to ascertain the communities it touched, the people it gave jobs to, and any landmarks it built that are still standing nearly eight decades later.

A key aspect of the New Deal is that many different agencies were involved in its projects. Franklin Roosevelt was elected president in 1932, and over the next decade or so, the federal government rolled out numerous agencies—the famed “alphabet soup” of the 1930s. They included the Civilian Conservation Corps, Public Works Administration, Civil Works Administration, and, most well-known of all, the WPA, which later kept its acronym but was renamed the Works Projects Administration.

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which was by far the most prolific agency in Idaho, was aimed at giving jobs in parklands to young, single men. The CCC was administered by the US Army, and in a military-like setting, these men built roads, infrastructure, and buildings in places such as Heyburn State Park and Payette National Forest. Idaho had 163 CCC camps—the second most of any state, after California. Continue reading →

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only