Most Idaho travel brochures won’t tell you that in just two days’ time you can see lava that came from thousands of feet beneath the surface of the earth, a legendary writer’s last resting place six feet beneath the earth, and stand 12,662 feet above the earth. But that’s just what my friend Tim and I set out to do last July.

I had spent most of my summer working at the Post Register in Idaho Falls. Although my internship had lasted three months, I didn’t feel that I knew any more about Idaho than before I came. (Though I could find Rexburg, INEEL and Blackfoot on a map).

Tim and I had two days to see Idaho, so we left Idaho Falls on a sunny Wednesday, shooting west down Highway 20. First stop, Craters of the Moon National Monument.

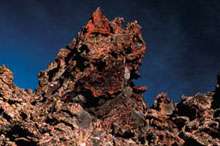

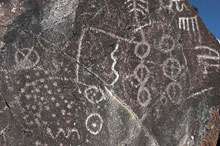

We turned off the highway and followed the loop that cuts through the monument. I tried to keep my eyes on the road but ended up staring out the window at the endless lava fields peppered with sagebrush.

The name “Craters of the Moon” was no coincidence. The entire preserve actually looked like the surface of a barren planet. It was a strange sight in the middle of scenic Idaho, a state I thought was famous for its mountains, valleys, streams, and lakes, not a giant magma wasteland.

Tim and I hopped out of the car at the foot of Big Cinder, the monument’s largest volcanic cone. We crunched our way up the massive black mound and I remembered my high school track days, running hundred-meter dashes on cinder tracks.

“You know, if you jump up and down on this stuff, it feels exactly like jumping on snow,” Tim said, snapping photos of the landscape.

“Yeah?” I said. I immediately began hopping and stomping like I hadn’t done since I was ten years old. It didn’t feel like snow, but there was an odd bounce to it, pushing me back up when I landed. Up and down, up and down, bouncing until I felt embarrassed.

We stood at the top of Big Cinder and gazed over the scenery below: brown and black lava fields and cinder spread over the land where the greens and browns of grasslands should have been. I thought I knew what natural beauty was—the rugged upward juts of mountains, ocean waters rolling on the horizon, the dramatic curves and drops of canyons and gorges. Craters of the Moon was just, well, beautifully strange.

I wasn’t the only one to think so. In the 1924 presidential proclamation that established it as a national monument, Craters of the Moon was called a “weird and scenic landscape peculiar to itself.”

Considering it was midweek, I was surprised to see several other visitors at the monument, driving around the loop and hiking up the cinder cones.

“Most of our visitors are just passing through,” Jim Morris, Craters of the Moon superintendent, says. “We’re between Yellowstone National Park and the Sawtooth Recreation Area. People pick Yellowstone as a destination vacation spot, and they’ll stop here on their way through.”

Two hundred thousand visitors stop at Craters of the Moon every year, and Morris estimates sixty percent of them don’t pick the monument as their “destination” spot.

Tim and I didn’t either. We hopped back in the car and took off down Highway 20 again. Next stop, Ketchum.

When we arrived in Ketchum’s surprisingly cosmopolitan downtown we were instantly surrounded by luxury SUVs and the summer resort crowd who could afford to drive them.

We knew what we had to do. We walked into the Sun Valley/Ketchum Chamber and Visitors Bureau to find out where Ernest Miller Hemingway was buried. Armed with directions to the Ketchum city cemetery and, more importantly, directions to Hemingway’s grave (back row, near the middle), we bolted out the door and sped onward.

At the cemetery, we found Hemingway’s headstone next to that of his fourth wife, Mary Welsh Hemingway. Hemingway’s grave was littered with coins, like a dry wishing well. Tim and I briefly considered collecting the change and using it to pay for our lunch.

“I think if he was still alive, he would have at least bought us a drink,” Tim said.

“You know, I don’t think it’s a good idea,” I said.

We took turns standing near the headstone and taking each other’s picture, proof that we’d been closer to Hemingway than anyone else we knew. Even if he was dead, I thought, paying my respects might bring me some good luck as a writer.

We saw no one else in the cemetery, but we weren’t the only fans who were curious about the grave. Laura Hall, information specialist at the Sun Valley/Ketchum Chamber and Visitors Bureau, says five to seven people come into the visitors bureau every day during the summer to ask about Hemingway.

“The majority of requests for Hemingway are from our male visitors, from college-age all the way up to sixty,” Hall says. “This was his very private place. He never wrote much about it—this was his American getaway.”

Hemingway wrote For Whom the Bell Tolls in suite number 206 at the Sun Valley Resort in 1939. After we visited his burial site, the only item left on our itinerary was our ascent of Borah Peak. I was excited, but infected with a nervous fear of the mountain—I didn’t want to know for whom the bell tolled; it was tolling for me.

Borah Peak, at 12,662 feet, is the highest point in Idaho and pops into the sky along Highway 93 about thirty-three miles south of Challis. As we drove toward the peak, the late afternoon sun painted the trees and valleys in a warm light and took my mind off the next day’s climb until we hit the dirt road leading to the Borah trailhead.

My car rattled over the bumpy road and Borah sat with its head nearly blocking the sun, laughing at us. We set up camp at the trailhead and slept fitfully until just before daylight.

We hiked up the steep trail in the shadow of the mountain, starting at an elevation of 7400 feet. Over the 3 1/2-mile climb, we would gain nearly a mile of elevation. As we pushed on past the treeline, the sun came up over Borah and lit the valley below. Even from where we stood, only halfway up the mountain, the view was spectacular. Deep green circles from irrigation sprinklers hung between ribbons of streams cutting across the valley floor, flat and what seemed like forever away from us.

We stopped for a quick change of clothes after the sun came over the mountain, then pushed on up the ridge. It was a comfortable climb until we met the boulders that mark the beginning of Chicken Out Ridge. From there, we scrambled up and over, trying not to look down on either side, each offering vertical drops one of my co-workers had warned me were “a quick exit off the mountain.”

The last bit of Chicken Out Ridge drops onto a snowfield traverse of about sixty feet to the other side. In celebration of my successful negotiation of Chicken Out, I chicken-danced across the snowfield.

No one laughed.

“Don’t get cocky,” a climber on the other side warned. I was definitely not funny.

The snow crossing behind us, we climbed what felt like straight up a never-ending mess of rocks to the summit. I stood at the top and looked at a 360-degree panorama of peaks: The Lemhi Range, the White Cloud Mountains, the Boulder Mountains, the White Knob Mountains, the Sawtooth Mountains, the Salmon River Mountains, and the Pioneer Mountains, all packaged together in a view that can only be seen by flying or by climbing.

We had reached the summit in a little less than five hours, taking about the same time as the many other climbers we saw that day.

“If you don’t mind the people, Borah is a nice climb within the reach of most advanced hikers,” Jerry Painter, co-author of Trails of Eastern Idaho says. “Summer weekends can be fairly crowded. If you go in the off-season (late September to early July), Borah is a serious mountaineer’s challenge. That’s when you find out it’s a real mountain. In the summer, it’s a kitty. In the winter, it’s a tiger.”

After three hours of running downhill from the summit, we arrived back at the trailhead. We threw our packs in the car and started the drive back to Idaho Falls.

We finished our journey in less than thirty-six hours, and we had worked in as much as we could as fast as we could. We saw the Craters of the Moon, stood next to the grave of a literary star, and got as close to the sun as we could get in Idaho. If the Gem State bordered the ocean, we probably would have taken a dip in that too. But instead we settled for a couple of well-deserved showers. Continue reading →