No products in the cart.

A Book of Beings

Greater-Than-Human Communities

By CMarie Fuhrman

A most unusual field guide to life in our part of the world has just been published. The author of the following story, who is an Idaho resident and one of Cascadia Field Guide’s three editors, explains the thinking that drove its combination of art, ecology, and poetry.

The Idaho Giant Salamander thrives in Idaho. This has nothing to do with loyalty to our state but everything to do with the ecological community that supports the Idaho State Amphibian. If the Idaho Giant Salamander is loyal to anything or anyone, it is to survival, and that survival can happen only in the unique bioregion found in parts of Idaho and a sliver of eastern Montana, an area I’ve come to call the Eastern Rivers community of Cascadia. Eastern Rivers is not a scientific term but a name my co-editors Elizabeth Bradfield, Derek Sheffield, and I gave to the ecological community existing within a region that includes most of the Idaho river basins and drainages. The word “community” matters to us. It is inclusive, specific and nebulous: community carries the ethos of our project, the anthology Cascadia Field Guide: Art, Ecology, and Poetry, whose pages became another home for the Idaho Giant Salamander.

Using the word community rather than bioregions was one of the somewhat unusual and innovative decisions we made when putting the anthology together. The ethos for the project was to present areas that functioned like healthy communities and the life therein as beings with equanimity and with kinship to the human beings who share these communities. We chose the word “beings” to reflect all life—from Cryptobiotic Soil to Bushy-tailed Woodrat to Human—as representative of the whole, whose members are dependent upon one another for survival. To present Mosquito and Red Osier Dogwood as Human neighbors is to ask readers to deconstruct human-centric thinking, to decolonize how we see our place among other beings, and to understand our dependency upon each other.

We also loved the fluidity of borders of communities, how they sometimes overlap and pay no attention to public or private designations, to forest or national park edges, to state or country lines. These beings do best in areas that sustain them even as their presence helps to maintain the health of each community. No conversation about kinship, community, or equality could exist without acknowledging culture—the ecological and ethnological cultures that exist, both Native and modern, within these communities. We hoped to hold natural and human history, culture, and art in something like a raindrop: fluid, reflective, nurturing, and alive.

Just as carbon is part of the whole of a raindrop, so then would poetry and art blend with scientific and Native nomenclature; narrative introductions with traditional stories; and medicinal or ceremonial uses with climate science to represent each of the 128 beings within the collection. How else could one understand a being so complex as the Idaho Giant Salamander, a being who feeds on Caddisfly, barks when startled, is eaten by Bull Trout and feels like wet silk and laughter when in the palm of your hand? How else to understand the importance of Horsehair Lichen as a food source or an impromptu beard when a tired hiker needs a laugh or a snowperson needs some facial hair? Or to know that sixteen thousand years before David Douglas, Nimiipuu had names such as páaps for Douglas Fir and héeyey for Steelhead Trout?

Reading this, you’ve probably spotted another somewhat unconventional choice: the capitalization of the names of beings. It’s strange to see that on the page, isn’t it? All the lessons that were taught to us about proper names and nouns are hard to forget. It looks like an error. Stands out. Which is why we made the choice to represent the beings in this way. Equality again. And why we refer to them with the pronoun “they” rather than “it.” This decision is inspired by Robin Wall Kimmerer’s embrace of “ki” as a pronoun and the work of others who ask us to consider the agency and animacy of nonhuman beings.

Imagine being asked what your mother is doing outside, kneeling in the soil, and replying, “It is weeding its garden. It loves working in the dirt.” This would be disrespectful and dishonoring. It would take away selfhood and relationship. The pronoun “it” would reduce your mother to a thing. If we were to create a collection that also functioned like a true community, then all life would have to have the same importance and have to be honored. Our book does not attempt to hold one being over another but regards all beings as equal.

CMarie and Idaho Giant Salamander. Courtesy CMarie Fuhrman.

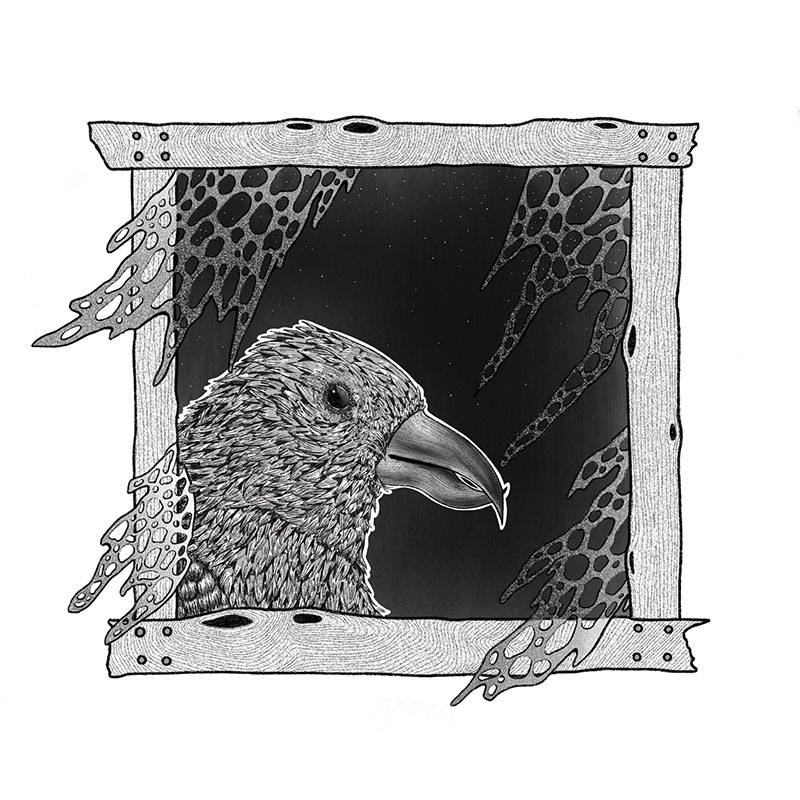

Cassia Crossibll. Illustrated by Xena Lunsford.

Columbia Desert Parsley. Illustration by Justin Gibbens.

Cover of the new book. Courtesy Mountaineers Books.

And equally accessible. Just as Native cultures used art to communicate, so does our anthology. Most field guides offer a photograph or scientific illustration to help wonderers identify beings but we felt it was necessary to do more than identify a being. We wanted to understand and identify with that being. I think here of the Salmon and the painting in Red Fish Cave in Hells Canyon. Though the art was created thousands of years ago, rendered in dots made by a fingertip rather than lines of a pen or strokes of a brush, I still feel a connection to it and still share something with the artist. Like that red fish, the art in our book is inspired and unique. Fourteen artists bring various translations, because we wanted to represent diverse ways of seeing. Each artist was offered a community of twelve or more beings and artistic freedom. The result is magical. The book holds drawings of Gull flying off with a stolen French fry, Cassia Crossbill looking thoughtfully from a window, and in the eastern river’s community, Justin Gibbens rendered an Idaho Giant Salamander in a natural history-inspired watercolor that gives a dreaminess and cuteness not often attributed to an amphibian but certainly felt when experienced in the wild.

As someone who spends a lot of time on Idaho rivers, in our wildernesses, and backpacking or hiking state and public lands, this project felt like a gift to me. A way to understand the beings that I meet in my wanderings, a way to strengthen my wild connection. But the result was more than that. Working on this project with Liz and Derek, as well as with scientists, biologists, poets, writers, academics, publishers, elders, spiritual leaders, and educators, I encountered a new sense of community. In the making of a book, my community and my awareness of how many people connect to this place and these beings tripled. What happened was symbiosis.

When I agreed to this project, I hoped that creating more wonder, curiosity, and understanding among human beings would benefit these greater-than-human communities, and I have faith that it will. I am equally delighted that the connection to the nonhuman creates understanding, wonder, and community between humans. Perhaps that is why the writer Drew Lanham calls this book “a feel guide.” Or maybe it is proof of how unseparated we are from all of the beings we share this place with.

Following are excerpts from the book:

Cassia Crossbill

(Loxia sinesciuris)

The only place in the world you can hear the burry, finchy warble of Cassia Crossbill and see their bright bodies—reddish orange yellow in males and greenish gray in females—dangling upside down from pine cones is in Idaho’s South Hills and Albion Mountains.

Cassia Crossbill looks like the other nine varieties of Red Crossbill in size and coloration and the characteristic shape of their bills, which appear twisted. In crossbills, the top bill curves one way and the bottom bill the other, like bent pliers. One important difference, however, appears in the thicker bill that Cassia Crossbill uses to pry open the scales of Lodgepole Pine cones as they slip a dexterous tongue in to retrieve their primary food source: Lodgepole Pine seeds. When hundreds of Cassia Crossbills are feeding this way, you can hear the lightest rain of the diaphanous husks falling to the forest floor and an occasional softly called kip. The second part of their Latin name, sinesciuris, means “without squirrels.” This refers to the absence of Red Squirrel in their habitat, a key condition that has led to the amazing coevolution happening between their bill and Lodgepole Pine’s cones.

Although others in Cascadia have surely known Cassia Crossbill for a very long time, contemporary scientists only became aware of them recently. And in 2020, the Badger Fire in the Sawtooth National Forest burned through about a third of their habitat. What other beings, we might wonder, have so far escaped our awareness, and will they survive long enough for us to meet them?

The Looking Glass

By Nick Neely

I tucked myself into a threadbare willow beside a cabin and tried not to flinch. The leaves cut my shape, just enough, and the birds came. The putters of their wingbeats announced three species: Cassin’s finches, somehow saccharine in their scarlet crowns; pine siskins, yellow-barred; and Cassia crossbills, elephantine by comparison, a heavier burst and slowing as they landed, brr-rump. They’d come for salt extruded from the concrete foundation. Slowly, I raised my binoculars. Beside a few old planks and crushed beer cans, they hopped, scratched, jostled—mouthed and digested this earth.

European folklore holds that, while Jesus hung on the cross, a roaming finch came to his aid, pulling at the nails in vain, bathing its plumage in blood, wounding itself, mangling its bill forever. The evolutionary explanation for the crossbill is simpler and no less miraculous: They are adapted for opening conifer cones.

Curl your index finger over the knuckle of your thumb, and you shape this bird’s namesake anomaly, which it jams between two scaly bracts. As it bites, its bill’s curved tips press in opposite directions, forcing the scales apart. Next it flexes its lower mandible (your thumb) sideways, using a hyper-developed muscle on one side of its face, to pry the scales wider. The bird’s pink tongue—so long that it wraps behind its skull when retracted, as in hummingbirds and woodpeckers—slips in for the seed in its papery skin. The bird husks the nut using a special groove on its upper palate. The crossbill performs this ritual, this chore, about 1,500 times a day.

As the birds lifted their heads from the dust, I studied those beaks. Cassia crossbills are found only in these mountains and the neighboring range. They have co-evolved with the lodgepole pines here, so that their bills have grown larger, on average, along with the cones. There are perhaps only four or five thousand Cassia crossbills in the world. They’re not likely to survive this century. Warmer temperatures are causing the South Hills’ cones to open prematurely and shed their seeds, the bird’s one and only staple. From under my willow I looked into those charismatic black reflective eyes. You could say they looked like coal.

Columbia Desert Parsley

(Lomatium columbianum)

“I have something to teach you” is something that Native people have heard for years from many beings. Indigenous languages, cultures, and spirituality are tied to the natural environment. The relationship sustained between the beings, Human and non, is essential to the health of both. One being critical in all aspects of that relationship and to many tribes throughout Cascadia is Cous, or Cous Cous (an anglicized version of Qawsqáws, the Umatilla word for this being), also known as Columbia Desert Parsley.

Early season hikers along Eastern Rivers delight in seeing and smelling this stout, fragrant plant, also known as Spring Gold. We are greeted by a being barely knee-high, a stocky soul with arms extending from the earth as if offering a bouquet in rays pinkish and lightly purplish—the color of amethyst and some types of wine. These blooms arise from taproots that allow this being to thrive on the dry, rocky slopes, making this display seem like a bright call, saying, “Here, I have something for you.”

Along with the joy of seeing beautiful Desert Parsley are the gifts Native people and others know the roots hold. For centuries, people Indigenous to Cascadia have held a thanksgiving to celebrate the onset of the harvest of Cous, and it is easy to understand why. Cous Cous roots resemble small sweet potatoes and can be eaten raw in spring. Desert Parsley is often ground into meal for finger cakes or dried whole—eaten this way, the root tastes like stale biscuits, hinting toward the name Biscuitroot. An infusion of the root is used to quell symptoms of the flu and colds; mashed and applied as a poultice, Desert Parsley draws out infection or helps heal Horse’s saddle sores. Warm Springs people use the paste to process buckskin, and others work it into their hair as a tonic against dandruff.

In so many ways, Qawsqáws may be trying to show us that culture is tied deeply to the land through the foods we harvest and celebrate; by extending beauty outward, others might see the beauty and value we keep underneath. Qi’ce’yew’yew’, Qawsqáws! Thank you, Cous!

The excerpts are from Cascadia Field Guide: Art, Ecology, Poetry, edited by Elizabeth Bradfield, CMarie Fuhrman, and Derek Sheffield (March 2023) with permission from the publisher, Mountaineers Books. All rights reserved. The book can be purchased at Mountaineers.org, elsewhere online, or wherever good books are sold.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only