No products in the cart.

A Fort in the Mind

A Child’s Silver Valley

By Jessica E. Johnson

In her new book, Mettlework: A Mining Daughter on Making Home, the author recounts the challenges of being raised in mining towns around the West, including those of Idaho’s Silver Valley, where her father was superintendent of the Lucky Friday Mine. The following excerpts from Jessica’s book, which begin with her family’s arrival in Kellogg, depict the difficulties she had coping as a sensitive child in the valley’s rough communities of the 1980s.

We arrived there in the afternoon, in the middle of someone else’s day.

The out-of-place feeling had a location in my chest, in my throat, where I wanted to be able to breathe without thinking about it. My mother, as if speaking from long experience, told me it would go away.

I started kindergarten there and learned how the out-of-place feelings could come again and again and squeeze out other thoughts. I wanted to read and they wanted to teach me letters I already knew. I learned a host of fears. A pack of loose dogs running the neighborhood tore a kitten to death in front of me.

I had to get home from the bus stop by myself, thinking about how to get around boys with their threats and sticks and their BB guns, which they were given at age four. I learned that to be out-of-place was to be vulnerable.

At the end of that year, we moved a few miles east, to Wallace into a Victorian that had seen its last updates in the nineteen forties. The house was on the edge of town, up a long gravel drive, with a concrete creek bed on one side and a mountainside on the other.

The yard was a long, narrow strip of lawn, and the mountain was for us to roam. When I dream about it now, the days are cloudy, the light blue, the colors sharp.

Wallace claims its old-timeyness in signage and on websites: historic Wallace, Idaho. When we lived there, the population sign said 1,200. (Now it’s 684.) Then, I-90 slowed to a downtown street with the only stoplight between Seattle and Boston. (Now, the freeway flows above the intact, historic-society-registered downtown buildings.)

The whole town lay within the span of a child’s mental map. We could walk to school, to the pool, to the library, to the downtown you-bake pizza shop, to the drugstore, to the grocery store, to a friend’s house.

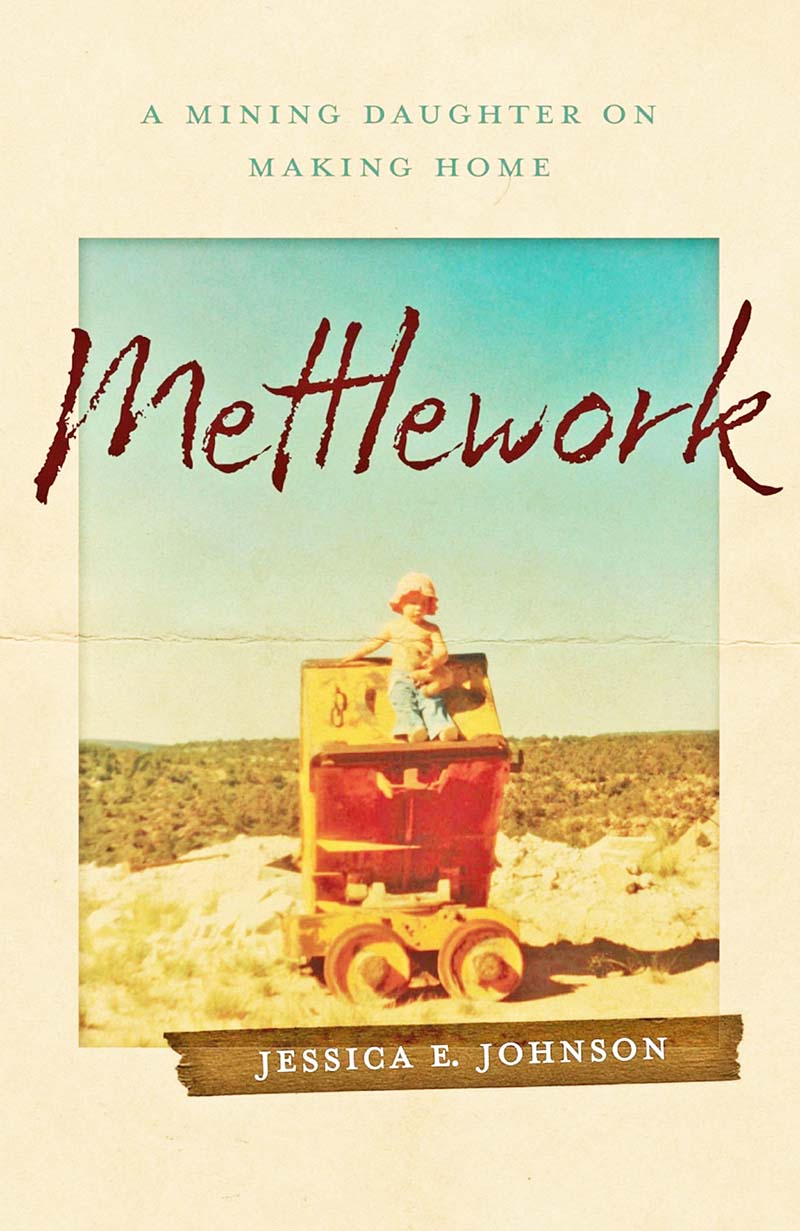

The new book's cover. Acre Books.

The author as a child in Wallace. Courtesy Jessica E. Johnson.

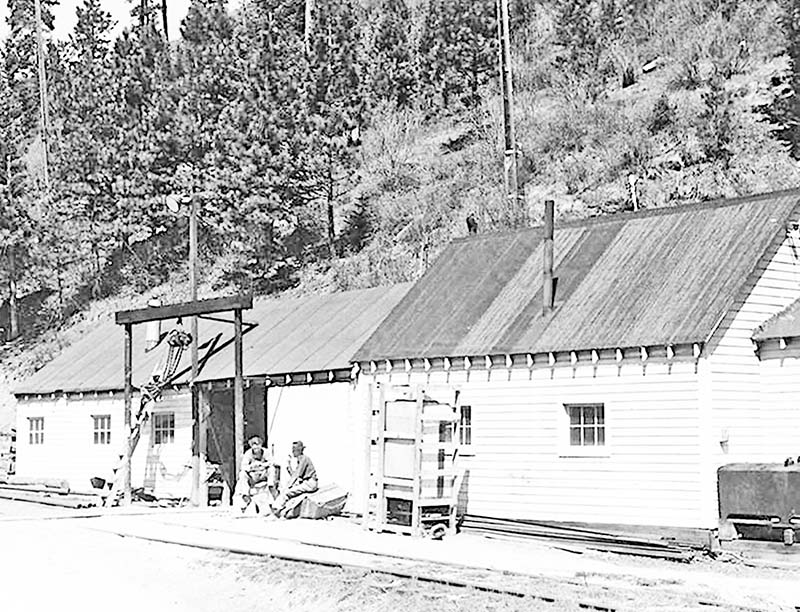

Lucky Friday Mine, 1947. University of Idaho Digital Collection.

Silver Valley sunset. Knowles Gallery.

Downtown Wallance. Rectify photo.

Jessica's family home in Wallace. Courtesy Jessica E. Johnson.

At the end of the workday there was a noticeable stream of cars down the freeway from Mullan, the last town before the Montana border, where they were still mining silver from a hole in the earth a hundred years old and more than a mile deep.

The Company’s office had been located in Wallace since its founding. The decisionmakers and their families had lived in close proximity to the consequences of their decisions, sent their children to local schools.

But just after we got there, the Company relocated all the executives to Coeur d’Alene, about an hour away and over a steep mountain pass, making us the only management family in a union town.

I might have felt this more, except that so many of the kids I went to school with were the children of single moms and absent dads, women who stayed and worked at the bank or the IGA or the downtown rock shop after the men moved on to another kind of labor. What made my brother and me most noticeably different, even when the miners went out on strike, was having two parents at home.

We lived in the relics of bygone boom times. We walked to school through late winter drizzle past ornate 19th Century mansions on what used to be a Millionaires’ Row. “That one has a ballroom,” said the neighbor girl we walked with, of a peeling pink-and-white, ornate hulk of a house.

The four-block downtown strip was preserved for tourists. Black-and-white photographs of miners, sheriffs, and unsinkable ladies hung in an old-timey saloon where my brother and I were taken for root beer floats in cowboy boot-shaped glasses.

Lawless Wallace was also known for its drug trade, which some of my classmates’ parents were clearly participating in, and the open operation of its brothels, which children talked about, understanding what they were but not what they meant for the women who worked there or the men, many of whom we must have known, who patronized them.

The brothels were located adjacent to the police station, and it was known that you could trick-or-treat them, so we did: a red staircase, a redlight bulb, and a plain white sign with the word Luxette in red cursive letters.

Another set of steps, wide and stone, led to the double doors of the town’s Carnegie library. I read the books it held like dispatches from the world beyond, small messengers of a seemingly endless body of knowledge that I was constructing as a kind of salvation.

****

The spring when I was finishing fifth grade in Wallace and playing softball and wearing miniskirts and neon spandex shorts with neon tank tops and occupying my imagination with the drama in my small friend group and running out of town up into Burke Canyon by myself, for something to do, to hear the sound of my own breath and feet, my dad was called up from the Friday to the corporate office in Coeur d’Alene.

We packed up the Wallace house and moved over the mountains. It was an hour and a half away but seemed like a world apart.

Though the office was on the edge of Coeur d’Alene, a town with its share of old houses and street trees and new subdivisions, my parents chose a little strip of road very far away from anywhere else, a one-street subdivision at the edge of a slowly industrializing prairie. The entrance was marked by a gun club.

After living in a company town with a sense of its history—at least the last hundred years of it—where you could hear and see evidence of the mines in the roadside piles of mine waste used to sand roads in winter, in the line of pickups rolling into town at quitting time, it seemed that we’d moved into a land disconnected from any kind of purpose besides the holding down of a fort in the mind.

****

Meanwhile, I remember instances of a prevailing cruelty that no one apparently questioned: a girl, skinny and notoriously mouthy, being thrown down the bleachers by a crowd of boys, and the teacher on duty seeing it, turning her back, and walking away as the girl howled on the floor, bleeding.

The quiet shaming of the solemn, pregnant fourteen-year-olds on the school bus, their bellies emerging from the frightening tininess of their frames. Girls wounded by their brothers’ knives and guns. The sixth graders who were regarded by adults as sluts rather than children. The neighbor who shot cocker spaniels if their owner wasn’t home during the daytime. The boys who shot at each other.

The tacit prohibition against talking about any of this, against disclosing any feeling that might render you vulnerable. The assumption of nearly every authoritative adult that people, no matter how vulnerable, are squarely responsible for their own pain, that it’s a result of poor choices or problems with character.

A pervasive philosophical indifference to the idea of help, to the idea that one’s circle of concern might extend beyond self and (at best) immediate family. The pervasive belief that people get what they deserve.

The world outside our house seemed not just difficult to enter, but incommensurable and frightening.

Jessica E. Johnson’s Mettlework: A Mining Daughter on Making Home (Acre Books, Cincinnati, 2024), is available wherever good books are sold or online from the University of Chicago Press.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only