No products in the cart.

A Sleeper Wakes

The Cook Creek Ridge Fire

By Robert W. Sisk

In the following excerpt from the new book Rampage by Firestorm, helitack crew pilot Robert Sisk describes a harrowing wildfire battle near Garden Valley. The excerpt is preceded by an introduction the author wrote for IDAHO magazine:

When I was an aerial firefighter and pilot for a helicopter attack crew, our team experienced firsthand how a lightning-sparked forest fire that at first seemed normal and had been controlled could turn within minutes into a nightmarish conflagration.

In late June 1979, when several bands of thunderstorms unleashed massive lightning strikes across southwestern Idaho, our helitack crew was alerted. We were a group of highly trained firefighters who used helicopters for fast and initial attack on newly started fires, especially those in inaccessible mountainous terrain.

Our foreman, Ray Patnaude, was a sixteen-year veteran of wildland firefighting who knew what to expect from the storm. He told us we’d be on duty at first light.

The next day, I flew firefighters to various blazes in the Boise National Forest around Garden Valley. On the afternoon of the second day, Helicopter H-10, our call sign, was summoned with a fire crew to Cook Creek Ridge, thirty-six miles north of Garden Valley.

This created uncertainty, because the previous day I had flown two men from Garden Valley to that same spot. Three other firefighters had driven from Lowman in a pumper truck to the scene, using old logging roads. All five had controlled the fire and were still on the site. Lookouts at Whitehawk and Scott Mountains reported a huge column of smoke with fire shooting skyward.

The Boise dispatchers weren’t sure if this was the same fire or a different one in the same area. They were concerned that it might be a sleeper: a potentially dangerous lightning-started fire that smolders and emits very little smoke. As the sun rises, warming the air, the winds begin to pick up, and the sleeper suddenly comes alive. When that happens, it can roar out of control, cutting off escape routes for firefighters.

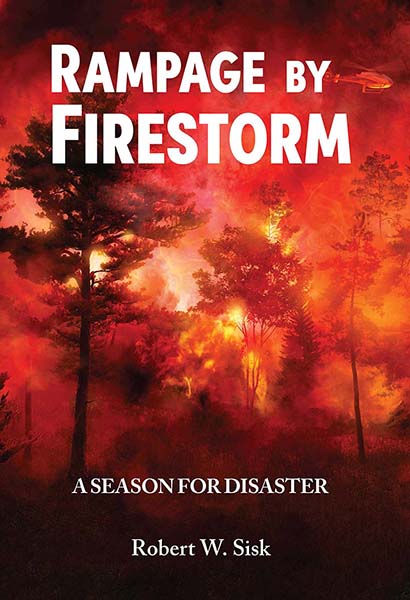

The book's cover. Sweetgrass Books.

Cutting heavy fuels at an Idaho wildfire. Idaho Department of Lands.

Heli-rappell training above Salmon. Charity Parks, USFS.

Idaho smokejumpers. NIFC.

Smoke from an Idaho wildfire. Idaho Department of Lands.

In boiling smoke and heat, we were tasked with a helicopter evacuation. In the following excerpt from my book that describes this scene, I refer to myself by my last name, just as I do the other members of our crew:

After liftoff, H-10 climbed steadily northeast. It would require climbing from 3,168 feet, Garden Valley’s elevation, to over 8,100 feet in order to clear the ridgeline just southeast of Scott Mountain.

The helicopter leveled off above the ridgeline, and the crew could see tongues of flames bursting out of the dense smoke about twenty miles from their position.

The crew at the fire were now saying that they were completely surrounded by fire and were unable to get out, although they still had a pumper truck with them. The radio traffic became heavier and more confusing.

The dispatcher interrupted and ordered silence on that frequency due to the emergency. He was now able to communicate with the trapped firefighters and would be able to determine what course of action to take for their safety.

Ron Lou, the firefighter in charge of the Lowman crew, again radioed that they were unable to escape the fire and were using what little water that was in the pumper to wet themselves down. He requested that the helicopter attempt to fly them out.

H-10 was at maximum power but still six minutes from the fire. Patnaude radioed that he had copied Lou’s transmission and that the helicopter would be over the fire in a few minutes.

What would normally have been a small controllable lightning-started fire had turned into a nightmare. The original fire had been controlled, but unbeknownst to the firefighters, one of the dreaded “sleepers” had suddenly sprung to life down a tree-covered hill approximately a half mile to the southwest.

Fanned by winds twenty to twenty-five miles per hour, the undetected fire began its race uphill toward the unsuspecting firefighters. As the fire gained in size and fury, it started climbing the trunks of the thick dry pine and fir trees.

As H-10 was approaching the fire, it was decided that [Dane] Lee and [Stan] Kolby would be dropped west of the fire on a logging road switchback to put them in a safe area. The normal circling and reconnaissance of the landing site, to check for hazards, was omitted due to critical life-threatening circumstances.

H-10 touched down on the curved portion of the logging road. The two firefighters leaped from the helicopter, dragging their packs and equipment with them. In seconds, H-10 was again airborne and back over the fire.

Patnaude made immediate radio contact with Lou and asked for directions to his location. It was impossible to see down into the fire because of the heavy smoke. Lou radioed that he could barely make out a patch of blue sky to the east of their location.

The helicopter quickly skirted the edge of the fire and smoke and was soon on the east side turning back to the west. Lou radioed that he had the helicopter in sight and that it was a little north of his location. Sisk corrected his flight path back to the left, but the trapped men could still not be spotted.

He advised Patnaude that the approach would have to be aborted if the men on the ground could not be located. Patnaude unfastened his shoulder harness, opened the door, and leaned out of the helicopter, desperately searching for the trapped firefighters.

Through the smoke, Patnaude was able to spot the pumper truck and then saw the firefighters huddled in front of the truck. He directed the pilot to the left, then through the swirling smoke and debris kicked up by the rotor wash. Sisk pinpointed the logging road and made a steep descent using a single tree by the road as a guide and a means to keep his bearings.

Because of the thick smoke and downwash from the rotor blades, Sisk could only see to his right about thirty to forty feet, barely outside of the helicopter’s rotor diameter. He instructed Patnaude to watch the left side and the tail rotor for clearance of trees and any other hazards during the precarious approach.

H-10 touched down cautiously on the logging road, the rotor downwash adding a cloud of dust and ashes to the billowing smoke.

Patnaude quickly herded three of the firefighters into the back seats of the Bell Jet Ranger. The firefighters had been advised prior to the extraction that no tools or packs were to be loaded onto the helicopter.

The weight with just the firefighters was going to be a critical factor in getting everyone out. With Patnaude back on board, Sisk lifted the helicopter to a hover, concerned about tail rotor clearance, as he made a right 180-degree pedal turn.

The heat from the fire ingested into the air intake of the turbine engine made the engine temperature gauge needle shoot to redline immediately. The winds and turbulence created by the raging fire suddenly spun the helicopter completely around, causing it to settle back toward the ground and become unable to climb the one hundred vertical feet required to clear the burning trees.

The pilot sideslipped H-10 back onto the road, touching down just as the helicopter began another spin and barely missed a burning stump. Reluctantly, one of the firefighters jumped out and ran for the protection of the pumper truck. The truck was becoming a concern now, the heat was beginning to blister the paint, and it wasn’t known how much heat the fuel tank could take before it exploded.

Once again, the helicopter lifted off. Again, the engine temperature went to redline, but this time H-10 was climbing slowly up through the dense smoke. In seconds, they broke into blue sky and fresh air. Choking and gasping, the men aboard the helicopter hungrily gulped the clean air into their lungs.

The helicopter started an immediate descent to the logging road a quarter mile south of the fire to drop the firefighters off. Returning to the fire, H-10 again approached from the east and began a descent back into the smoke. Spotting the guide tree, the pilot shot the approach to the same landing spot. Two more fireighters were quickly loaded, and the same departure route was followed. One firefighter, Ron Taylor, remained to be airlifted from the fire.

Patnaude and Sisk made their final approach back into the inferno. The fire and smoke had grown in intensity making it more difficult to see the landing spot. Patnaude was again leaning out of the open door, shouting instructions over the intercom, the roar of the fire and helicopter noise making it difficult to hear. Sisk spotted the now familiar tree and once again landed close by.

Dodging falling, burning debris, Taylor made a run for the helicopter and leaped into the back seat. As if sensing that it had completed its task, the helpful tree suddenly erupted into a flaming torch. H-10 struggled into the air and again the force of the heated wind spun the helicopter around. The tail rotor barely cleared a fully engulfed burning tree, and the paint on the tail boom began to blister from the intense heat.

As the helicopter spun, it was also lifted by the same erratic winds and boosted over the burning trees into the clear. Taylor was reunited with the other firefighters on the logging road. Luckily, the firefighters suffered only slight burns and some smoke inhalation.

Lee and Kolby, who had been dropped off in a safe area while the emergency evacuation was ongoing, were picked up and reunited with the rest of their crew. By now, H-10 was critically low on fuel and headed to the Elk Creek Guard Station, a few miles north, for refueling.

Air tanker planes began dropping fire retardant on the raging fire in an attempt to slow its progress. After refueling, H-10 began ferrying newly arrived firefighters from Elk Creek to a safe area near the fire so they could begin a ground attack in conjunction with the aerial assault from the air tankers.

The fire burned out of control for a week, eventually consuming more than seven hundred acres of prime forest. Seven airplanes, three helicopters, and two hundred and fifty firefighters finally brought the fire under control.

Rampage by Firestorm: A Season for Disaster (Sweetgrass Books) is available in softcover at various local retailers, as well as online and through Farcountry Press at (800) 821-3874, farcountrypress.com.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only