No products in the cart.

Corey and Bros

By Bianca Dumas

Photos courtesy of University of Utah J. Willard Library Ski and Snow Sports Archives, Alan Engen Ski History Collection

I got a one-word text from my son Gordon in McCall: “Whoa.”

Attached was his snapshot of a framed black-and-white photo on the wall of Shore Lodge that shows two men holding silver trophies. I zoomed in on the brass name tag and saw that one of them was Olympic skier Corey Engen, a McCall hero.

Gordon was spending the winter in McCall and he loved everything about it. He loved the family feeling of the town: seeing toddlers ski between their moms’ knees, watching school kids get off the bus for race days in the Soda Pop League. He loved how skiing was at the center of community life, and he enjoyed becoming a part of it. Even though Corey Engen died at age ninety back in 2006, his photo sparked a connection between my son and me: a shared love of old stories, old-time people, and skiing.

Corey was one of three Norwegian brothers who came to America to look for work in the 1930s. Alf, Sverre, and Corey Engen were born in that order and came to America in that order. Alf became the most famous among them but Severre was a filmmaker and Corey was a famous fixture in McCall for a half-century. Although Americans had little work during the Great Depression, the Engens were able to make their way as exposition ski jumpers, then competitive ski jumpers, then ski racers. Together, the brothers amassed a thousand trophies across all four ski disciplines: ski jumping, cross country, alpine and slalom. Corey was captain of the 1948 U.S. Olympic ski jumping team and took bronze in the jumping portion of the Olympic classic combined event, involving both jumping and cross-country. He won twenty-two gold medals in national competitions and was inducted into the National Ski Hall of Fame in 1973, one of several halls of fame into which all three brothers were inducted.

I was glad Gordon was in McCall that winter and wished I could be there with him. I’m from the West, and had imagined I’d raise ski kids. I wanted to sign them up for their elementary school’s ski program and let them ride the bus to the slopes on Friday afternoons. The family would get season passes, I thought, and we’d spend our weekends skiing together and would become part of a mountain community.

It never happened. My husband was from a different climate and was wary of skiing. We moved away from the mountains and eventually found ourselves wintering in Florida, where we took up snorkeling and paddling through the mangroves. But when the kids became adults, we all came West again and our son moved to McCall just in time for its snowiest season in decades. He bought a pass to Little Ski Hill and taught himself, which came naturally after his years of skateboarding and surfing. Before long, we were talking about skiing together.

“Mom,” he texted, “next year: you and me. It will be so much fun!”

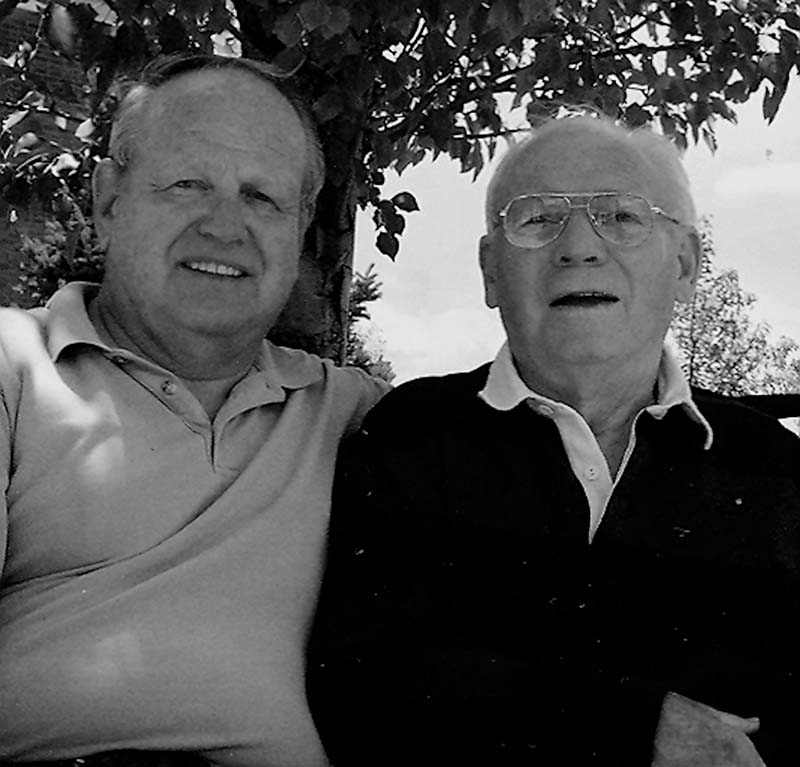

Alan Engen (left) with his Uncle Corey, 2004.

Skiers at Brundage Mountain in McCall. Glenn Gould, Creative Commons.

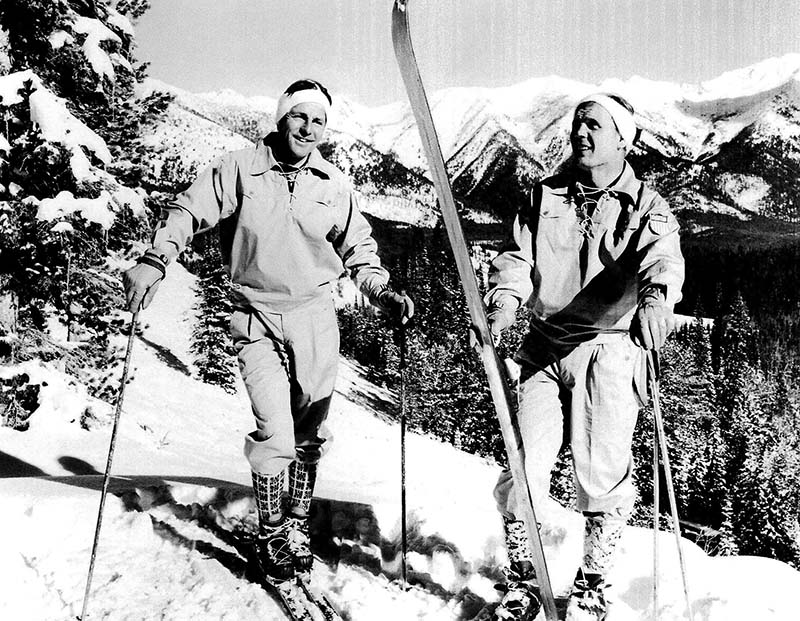

Corey Engen as a double in the film Northern Pursuit, Sun Valley, 1940s.

Corey ski-jumping on Ruud Mountain, Sun Valley, circa 1946.

The Engen brothers and wives in Sun Valley, circa 1968.

Sledding on McCall's Little Ski Hill. Glenn Gould, Creative Commons.

From left, Alf, Sverre, and Corey on the set of a ski film.

Walter Prager (left) and Alf, the US Olympic Ski Team coaches in 1947.

I wasn’t sure if I’d get back on the slopes, but Gordon’s enthusiasm revived my interest in researching skiers of the past. I got in touch with Alan Engen, the son of Alf, to find out more about the famous family. Alan and his wife Barbara invited me to their house, sat me down at their dining room table, and told me stories. We had a lot in common. My family had come to America from Italy, and I have the same feeling about my grandparents that Alan and Barbara have about Alf, Sverre, and Corey: a sense that while these were the people you were closest to in the world, they also were somehow otherworldly.

To Alan, they’re nearly mythical. He writes in his book, For the Love of Skiing, “As I was growing up, I saw my father and uncles as…representatives of winter legends of Norse mythology. I imagined all of the Engen brothers with their great physical strength, competitive drive, and love of winter as evolving into skiing icons and in truth, they actually have.”

None of my family members became icons, but I still share Alan’s awe. Our loved ones were from places and times that made them better than us in every way: stronger, more capable, and ready for anything. The Engen boys’ father died at only 31 years of age and his young sons supported the family by catching eel and fish. After seventh grade, they began working full-time. Alf’s first ski jump in the United States was done with tenacity and little else. He wore street clothes and town shoes, and used a borrowed pair of jumping skis, which he tied to his shoes with leather thongs. When they were on the ski jumping circuit, Sverre had to build the jumps with a pick and shovel before the exhibitions could be held. And young Corey got their mother across the Atlantic to a new continent all by himself.

The second I got back into my car after this talk, I texted Gordon. “Alan and Barbara are amazing. Wait till you hear everything they told me.”

When the Engen brothers came from Norway to the Intermountain West, they brought ski culture with them. As the public became inspired by the feats they witnessed at ski jumping expositions, they starting taking to the hills themselves. Alf was hired by the U.S. Forest Service to scout out locations that would make good ski hills, and he eventually helped lay out the terrain for about thirty resorts. In Idaho, these included Sun Valley, Bogus Basin, Bear Gulch, and Magic Mountain.

In McCall, Warren Brown had purchased land from Boise Payette Lumber Company that he scouted with Alf, who decided it would do for a ski hill. Brown donated the parcel to the Forest Service, which built the first lodge at Little Ski Hill in 1939. When asked who he’d recommend to run the ski programs, Alf named Corey.

After Corey moved to McCall, he bought the only gas station in town and purchased the rights to own and operate all future stations. Then he spent twenty years training kids. Corey’s Mighty Mites learned to master all four ski disciplines and competed in Four-Way competitions. Their training also required the development of several kilometers of Nordic tracks in McCall, which eventually would host the Junior National Nordic Championships.

In the mid-1950s, athletes began to specialize in just one area of skiing. Corey not only adapted to this change but coached kids to greatness in each specialty. His son David Engen became an alpine champion, as did Patty Boydstun, who raced in the Olympics. Mack Miller became an Olympic cross-country racer. Lyle Miller competed four times in the Olympic biathlon. In all, Corey trained eleven champions in all four ski disciplines.

When he felt that the students needed steeper terrain than the skill hill to practice on, he worked with Warren Brown and J.R. Simplot to develop Brundage Mountain Resort, where he eventually became an owner and where the ski school bore his name.

Occasionally, the brothers demonstrated ski jumping during McCall’s Winter Carnival, where Alf set the record with a 211-foot jump. Little kids awaited the day when they were allowed to graduate to the big jump like their heroes, and even in this area, champions were produced. Lloyd Johnson was proclaimed the “world’s smallest ski jumper” when he took to the air during that first Winter Carnival, and he kept jumping all his life. In his career as a wildfire fighter, he caught a different kind of air in helping to pioneer smokejumping.

In Sun Valley, Corey also worked alongside his brothers as movie stunt doubles. In a 1940s war film called Northern Pursuit, Corey played a German spy and chased Alf—who was doubling for Errol Flynn—down the hill on skis, flying over huge cliffs. In other films, like Ski Aces, the three brothers played themselves, but they also did all the heavy lifting for the crew, as nobody else could ski. Once all the equipment had been taken up the chairlift, the Engens would have to scout out the locations for the shots they needed that day, and then ski in with the heavy 35 mm equipment. When the locations were too difficult to reach even by snowshoe, two of the Engens would make a chair with their hands for the cameramen to sit on, and then ski them to the spot. The brothers skied their roles for the film and later skied out the cameramen and equipment as well.

All this really got Sverre’s gears turning. “After seeing what could be done by cameramen who couldn’t ski, I realized what an advantage one would have being able to ski to where the action was, and to be able to follow the skiers down the mountain,” he wrote. He started making his own films, skiing along with his subjects. These included Champs at Play, a film about Corey’s success coaching the McCall Mighty Mites. Sverre eventually toured the U.S. and Canada with his films, and he may have been the first skiing filmmaker in the nation.

What’s so remarkable about the Engens is that each of the brothers excelled in all four ski disciplines, each of them became instructors, each was instrumental in developing one or more ski areas, and each of them did something unique to further ski culture in the Intermountain West. Alf developed new powder skiing techniques and teaching methods. Sverre was a filmmaker, writer, and avalanche mitigation pioneer. Corey was a notable trainer and the only one to compete in the Olympics, under coach Alf.

Gordon loves skiing with the same group of people every day, on the same terrain, falling in love with the powder and the grand views and the cold and the history. Among ski people, even the young care about those who have gone before them. All this shared experience, especially when it involves hard work and days spent outside, seems to create deep connections.

As a parent, you sometimes get the things you wanted in a roundabout way. I wanted my kids to have the kind of community that grows up naturally around skiing, and now my son is finding it for himself.

We hit the slopes together in early December. “Do you think I’m crazy not to be nervous?” I asked as we rode the chairlift up to my first run in twenty years.

“No way,” Gordon said. “It’s just like riding a bike.”

Which proved to be true. While I skied somewhat cautiously downhill, my son skied backward alongside me. Then he turned, tumbled, and righted himself while still skiing. He hit a side jump, landed far downhill from me, and waited.

“By gosh, Mom,” he said, mimicking the Engen brothers’ Norwegian accent. “You might not be the fastest skier on the hill. But, by gosh, I’m gonna make you the prettiest.”

Alf famously told Nick Nichol, who began as a ski instructor in 1972, that he’d make him into a pretty skier. “I try not to brag, but that’s exactly what he did,” Nichol told me over the phone. “I had the privilege of doing all the powder skiing in five or so promotional films because of what they called the grace of skiing.”

I recently told Alan, “Every time I see a picture of your dad, I get a tear in my eye. I feel like he was my own grandpa.”

Alan nodded. “Everyone felt that way about Dad.”

Barbara said she misses the times the whole family sat at the dinner table, telling stories and laughing. “They were fun to be with.”

All three of the Engen brothers skied right into their old age, and lived for almost a century. Despite years of flying hundreds of feet off ski jumps and sometimes landing hard enough to break their skis, they kept going. Sure, they had achy backs and sore ankles, but they never stopped.

Alan himself has been a ski champion in every discipline, an Olympic torch-bearer, a ski instructor, a writer, and historian. He was inducted into the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame alongside his dad and uncles. He and Barbara will be honored this year at the International Skiing History Association awards banquet for their film, Alf Engen: Snapshots of a Sports Icon.

And me? Over a few days, Gordon made me a better skier. He reminded me to make my turns from the hip, not the shoulders, and got me leaning forward in my boots. One of his friends joined us on a lap and that night over drinks in the lounge, Gordon told me what his friend had said: “Your mom isn’t fast, but she’s a really pretty skier.”

Not the fastest, but the prettiest. A little shiver went up my spine. Whoa.

If you enjoyed this story, please consider supporting us with a SUBSCRIPTION to our print edition, delivered monthly to your doorstep.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only