No products in the cart.

Downey—Spotlight

Where Heaven and Earth Meet

By Jay G. Burrup

I remember Downey’s small but impressive Marsh Valley Hospital of orange brick. It was built on North Main Street in the late 1940s by energetic civic leaders, including my grandfather, William E. (“Ed”) Burrup, who received only a fifth-grade-equivalent education. When I was five years old, Grandpa suffered a severe stroke on a hot August day and was confined to the hospital for five months before he died. I daily accompanied my parents and elderly grandmother to the hospital to check on him. Hospital rules declared I was too young to enter his room, so I either sat alone in the waiting room or crouched at the hallway entrance until it was time to leave. One day, a nurse wheeled my beloved grandpa out to see me in the waiting room. He reached out to touch me, and gave me a weak but crooked smile. The drained and almost lifeless man who mumbled a greeting when he saw me unnerved me to the core. I started crying and clung to my mother’s leg for reassurance. The nurse whisked Grandpa away. That was the last time I saw him before he left Downey for heaven.

In subsequent years, I spent time in the hospital for removal of my tonsils, repair of a broken leg, treatment of a torn sternum, revival from dehydration by the flu, and so forth. In all those situations, I was operated on or repaired by Downey’s renowned Dr. Leo G. Burkett, a superior general practitioner. He was assisted by a team of competent and caring nurses in starched white uniforms.

I’m among a few thousand favored souls who know that heaven and earth meet in Downey. Evidence of this claim presides over the southern mountain range of the historic and semi-arid Marsh Valley in Bannock County: the majestic and locally revered Oxford Peak (elevation 9,282 feet). The rounded twin peaks of this striking mountain become visible as travelers leave Inkom on Interstate 15 and head for Malad, but only from Downey do they present their most picturesque angle. Many former Downeyites, like me, say life could take them away from Oxford Peak but it could never take Oxford Peak out of their memories or hearts. A former native, Clark Davis, wrote a country western song about it while feeling homesick in San Francisco in 1964 (you can listen to it on clarkkdavis.bandcamp.com/track/oxford-peak). The peak and valley will call out to you, as it still does to him and thousands of current and former Downey/Marsh Valleyites.

Red Rock Pass, which lies at the northeastern foot of Oxford Peak, was the rupture point where the ancient Lake Bonneville overflowed its banks. That Pleistocene-era pluvial lake covered thousands of square miles in southeastern Idaho, eastern Nevada, and much of Utah. Its shoreline extended two thousand miles and its waters reached about one thousand feet deep in some areas, such as the contemporary Salt Lake City. The lake broke out of its confining barrier about fifteen thousand years ago and disgorged its floodwaters north to the Snake River. The Great Salt Lake, about a hundred miles south of Red Rock Pass, is the most significant remnant of Lake Bonneville’s eventual demise. At the base of a small hill at the pass is a historical marker for the lake.

North of Red Rock Pass lies Downata Hot Springs, a geothermal water resort with swimming and soaking pools and camping facilities. For decades it has been (and continues to be) a favorite site for regional family and group reunions.

Members of the author's family in Downey, 1940. Courtesy Jay G. Burrup.

The Hotel Oxford opened in 1912. Courtesy Nola Hart Nielsen.

Lester Hartvigsen, 1937. Courtesy Jay G. Burrup.

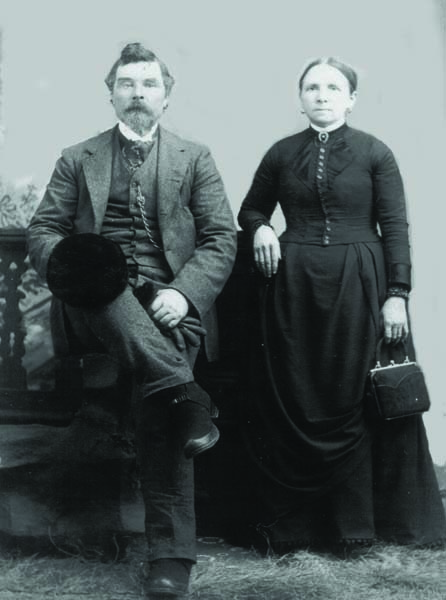

Early Marsh Valley settlers William W. and Laura Woodland. Courtesy Jay G. Burrup.

Oxford Peak seen from the Downey City Cemetery. Jay G. Burrup photo.

Oxford Peak dominates Downey. Michelle Brown Jones photo.

Postcard of Downey railroad depot, 1915. Courtesy Jay G. Burrup.

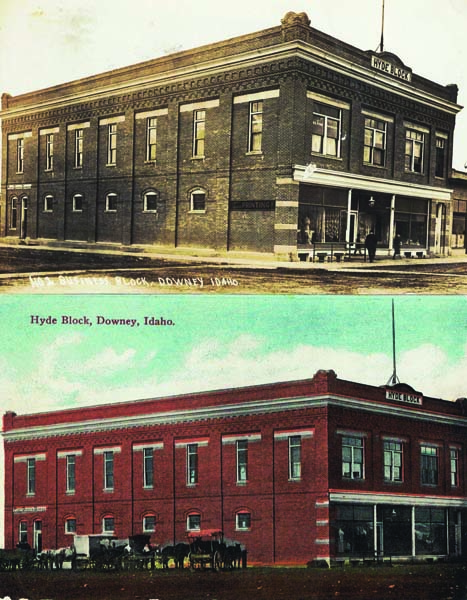

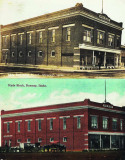

Two postcards of Hyde Block, 1910s. Courtesy Jay G. Burrup.

The city offices are undergoing renovation. Jordan C. Sackley photo.

Postcard of Downey, circa 1910. Courtesy Jay G. Burrup.

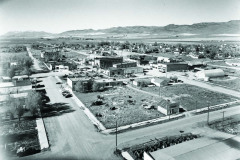

The business district, circa 1958. Larry Denney photo.

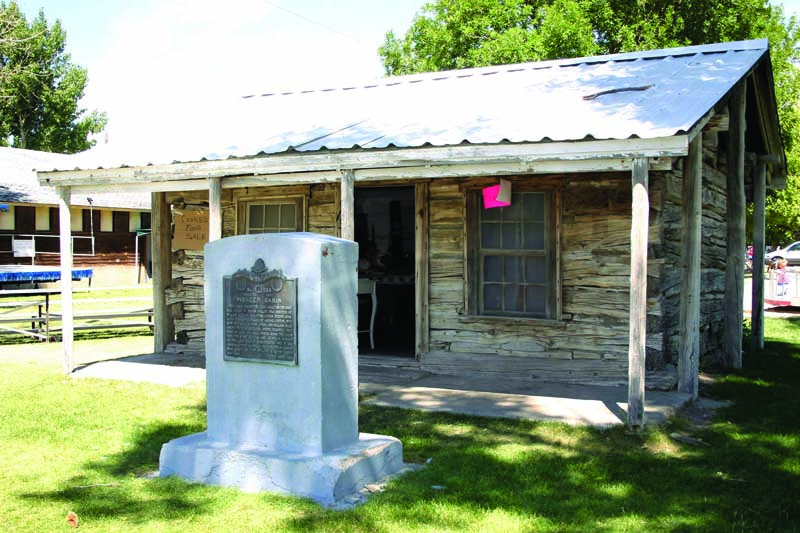

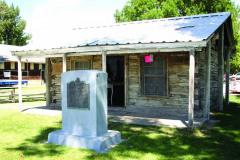

One of the area’s first log homes, built in the late-1860s. Courtesy Nola Hart Nielsen.

The butte at Red Rock Pass. Jordan C. Sackley photo.

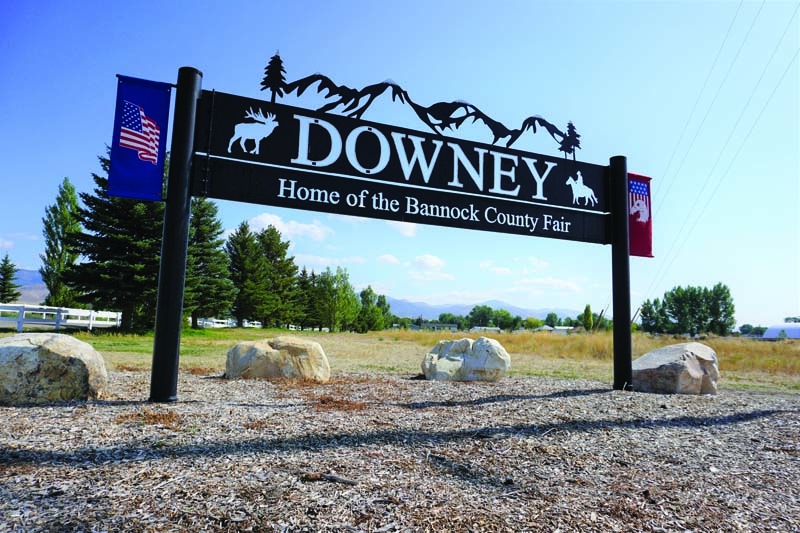

The welcome sign, by Downey native Kash Morrison. Jordan C. Sackley photo.

Much of southeastern Idaho was settled by members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) under the direction of church leaders in Salt Lake City. As Utah Territory’s population burgeoned from large influxes of European immigrants, subsequent generations of Utahns wanted property on which to establish themselves and their generally large families. Idaho Territory became an attractive pressure release valve. In 1860, three years before Idaho Territory was organized, LDS settlers colonized permanently in Franklin, about a half-mile over the Idaho/Utah border. Many of Marsh Valley’s earliest white settlers were church members, too, but they moved to the area on their own volition for personal economic reasons. The valley was a lush locale in which to raise cattle and horses, because of the exceptionally tall grasses that grew along the meandering Marsh Creek, which feeds into the Portneuf River near McCammon. The first founding LDS families were the interrelated Woodlands, Wakleys, and Whitakers, who moved from the Willard, Utah, area to Marsh Valley in 1864-1865. More families followed, especially from the Kaysville and Ogden, Utah, area. A stout, towering mountain on Downey’s west side is Wakley Peak (elevation 8,800 feet), named in honor of settler John Nelson Wakley, an early eastern Canadian convert and polygamist who fathered more than two dozen children with two wives.

During 1867-1869, the Fort Hall Indian Reservation was established, and Marsh Valley settlers learned they were squatting illegally on Native American ground. Periodically, the government’s Fort Hall Indian agent threatened the settlers with forced removal, but few were ever expelled. In 1889, after such failed attempts, the settlers successfully petitioned Congress to redraw the southern reservation boundary north to the McCammon area, thus allowing the Downey area settlers to legally own their by then long-established homes and cattle ranches. Dry farming of wheat developed in the 1890s.

The Oregon Trail’s Hudspeth Cutoff (pioneered in 1849) bisected Marsh Valley from east to west, several miles north of Downey near Arimo. The Idaho Gold Road bisected Marsh Valley from south to north en route to Montana. Dramatic stagecoach robberies occurred in the 1860s-1870s near the Malad Divide and north at Robbers’ Roost near McCammon. The Hayden Geological Survey crew traveled through Marsh Valley in June 1871, en route to explore what later became Yellowstone National Park. Two of the crew, famous artist Thomas Moran and photographer William Henry Jackson, made sketches and took photos of Marsh Valley’s starkly picturesque Red Rock Pass and Portneuf Canyon. Construction of the Utah and Northern Railroad reached Downey and Oneida (now Arimo) in May/June 1878. The rails linked Salt Lake City with the rich mines at and near Butte, Montana.

Uncertainty exists regarding how Downey acquired its name. Some early locals stated it was named after a Mr. Downey, a high-ranking railroad official, but my research efforts have failed to find anyone named Downey among then-contemporary officials of the Utah & Northern, the Oregon Short Line, or the Union Pacific. Another early resident claimed the name was derived from a humble railroad tie worker, which appears to be the more logical explanation. Apparently, Mr. Downey never returned to the burg to claim the honor of being its namesake. The first mention of Downey in a published source seems to be in a railroad guide dated April 1882.

In 1894, William Alonzo Hyde, an enterprising merchant from Kaysville, Utah, established himself at “Downey Station” and built a general mercantile store near the railroad tracks. His younger brother, George Tilton Hyde, soon joined him, and they became the official founders of Downey proper. The townsite was surveyed and platted in traditional LDS fashion—a grid system with very wide streets. Downey’s post office was established that year in the Hyde Brothers’ store.

Civilian Conservation Corps camp #560 was established in Downey in early 1939. It closed in mid-1942 and was soon repurposed as a conscientious objectors’ camp during World War II. Dozens of Mennonites and others from the Midwest who refused to fight were assigned there. In 1991, Idaho State University Press published a small book by John Olinger that documented the camp: A Place of Conscience: Camp Downey.

Before construction of Interstate 15 between Malad City and Pocatello, Downey occupied the important junction of Highways 91 and the old Highway 191. Travelers between Salt Lake City and Pocatello had to pass through Downey. Prior to the late 1970s, the town hosted numerous roadside gas stations, motels, and cafes. But like Radiator Springs in the Disney movie Cars, travelers’ need for speed on an interstate dealt a severe blow to Downey’s economy and growth. Even though the interstate bypassed the town by only three miles, its economic decline can be traced to that event, along with the dwindling of small family farms, and even the lack of a general practitioner to replace Dr. Burkett. Those blows, however, did not eradicate the resilient spirit of the tightly-knit community.

When the late Downey Mayor Dennis Phillips wanted to commit the town’s history to print, he organized the Downey History Committee, which produced an impressive three-volume set in 2016 titled, In the Shadow of Oxford Peak: A History of Downey, Idaho, and Surrounding Area. Rex Nielsen, the current mayor, and city council members are devoted to reinvigorating Downey’s economic health and have commenced major repairs of the century-old city offices.

The post office is on the west side of Main Street, south of the hospital, just where it was when I was growing up in Downey decades ago. Dale Davis, my close friend’s father, served as postmaster. He and my brother persuaded me to collect stamp plate blocks (a corner grouping of four new stamps that ideally include the serial sheet number) whenever a new stamp was issued. Besides supervising the town’s mail service, Dale raised, broke, and shoed horses, and excavated and delivered truckloads of Marsh Valley’s finest black peat moss to support his family. His wife Jeannine taught piano lessons to hundreds of valley residents. The Davises sent my friend Grant and his brother Daniel to study at Harvard University.

Adjoining the post office was the Downey Theater, operated by Ray and Maxine Horsley, who also owned Downata Hot Springs. The movie ticket prices were based on age—around twenty-five to thirty-five cents per kid, and a little more for adults. Every household in town received a monthly flier in the mail that announced the movies for the upcoming weeks. At our house, this movie calendar hung right next to our party-line telephone. The theater was an enchanting place that brought world entertainment to us 750 Downeyites and several hundred more people who lived on farms in the “suburbs”: Swan Lake, Cambridge, Virginia, and Arimo. Whenever the theater’s film projector malfunctioned or the film broke, impatient moviegoers stomped their feet until the entertainment resumed. Today the theater lies empty, dusty, and silent.

Next to the theater sat the IGA grocery store, run by Jay and Ellen Larsen. The store stocked ice cream sandwiches and popsicles during Downey’s hot summer days. The flavor that seemed to deplete first was blueraspberry, my favorite. When I was sixteen, the store’s chief clerk, Donna Burton, called me early one Saturday morning and invited me to work as a box boy—on a probationary basis. I was stunned by this unexpected offer. Years later, I figured out that my dad had proposed the idea to Donna, and she and Mr. Larsen agreed to give me a chance to prove myself. I think I weighed about one hundred and twenty pounds at the time (sopping wet), so hefting twenty-five to fifty-pound bags of flour, potatoes, sugar, dog food, and vats of butchered chicken blood and freshly butchered meat scraps provided a demanding physical workout. I earned $1.35 an hour, and no one tipped box boys back then, especially in rural Idaho.

The grocery store, located in the Hyde Block building, was Downey’s business and social center from about 1910 to the 1960s. It was (and still is) an impressive two-story reddish brick building with a large basement. In 1912, the building’s top floor hosted an immense community celebration for the completion of the Portneuf-Marsh Valley Irrigation Company’s canal system and the grand opening of Downey’s impressive Hotel Oxford. The event was attended by the governors of both Idaho and Utah. The large second-story room has also hosted LDS congregational meetings, community dances, parties, political rallies, and even boxing matches. Later, it hosted professional offices, roller skating events, and apartments. Downey’s only grocery store closed several years ago when the owner died and his widow moved away. The building was recently purchased by Ben and Shannon Sutorius and is currently undergoing extensive remodeling and repurposing as an artist’s studio and family residence.

My duties as a grocery store box boy required that I mop the floor of the entire store before we closed each Saturday evening. The mopping required a good hour of sweaty effort, and it had to meet Donna’s expectations. Working in the grocery store introduced me to many aging valley residents—children and grandchildren of Downey’s and the valley’s founding settlers. I often asked my dad, a lifelong Downey native, who so-and-so was and how he/she related to others in the community. Frequently, he informed me that the person I had inquired about was either his second or third cousin, once or twice removed—and thus my shirttail relative. This was one way I learned early that in small towns one needs to exercise caution about opinions formed and verbally expressed.

Across the street and south of the grocery store sat Max Valentine’s barber shop and a beauty salon run by Rose Lee Hill Evans that seemed to be always bustling. Adjoining the beauty corner was Downey Public Library, at first staffed by Marie Galloway and then LeOra Bloxham. When the library opened, we were certain that Nirvana had settled permanently in our little town. I read all of the Happy Hollisters, Hardy Boys, and Nancy Drew series. After my box boy career, I was offered a higher- paying job at the library. I took it, and that decision made all the difference in the world to my later professional career as an archivist.

When I was about seven years old, I once visited Downey’s liquor store. At the time, my father had suffered a heart attack, and because his heartbeat was so slow, Dr. Burkett prescribed a couple of shots of whiskey each day to speed the beat. It had been many years since my dad had imbibed. He couldn’t go to the liquor store for the “medicine,” so he sent my mother and me to fetch it. Even as a youngster, I perceived how uncomfortable Mother seemed while we stood at the counter and waited for the clerk to select and ring up a bottle of Old Crow. Mom paid for it and then asked the clerk to deposit the bottle in a brown paper bag. Apparently, my very religious mother thought no one would suspect what the brown paper bag contained when she slipped out of the liquor store with me in tow. A few days later, my dad let me lick a couple of drops of whiskey off the cork stopper. The taste was awful, and I choked and almost threw up. Dad was pleased I didn’t like the taste, and to this day, I have no attraction to alcohol. The remainder of the Old Crow aged under our kitchen sink for another twenty years. It resurfaced only occasionally, when a neighbor implored my parents for a snifter to make a hot toddy during severe cold and flu seasons.

On the east side of Main Street at the intersection with Center Street sat Downey State Bank. It was established in 1910 and remarkably—if not miraculously—it survived the Great Depression. The bank later was acquired in the 1980s by the older, Malad-based J. N. Ireland Bank. During my early childhood, its interior wasn’t much different than when it was founded more than a half century earlier. One of the bank’s directors and our neighbor, Harry Bowen, sat part of the day in a 1930s steel frame lounge chair smoking a cigar and chatting with customers who came to deposit or withdraw money. A small customer counter in the foyer displayed a chained copy of a 1911 promotional booklet titled Downey and Marsh Valley, Idaho. It was published by the famous Kidder-Peabody Corporation of faraway Boston, which underwrote the Downey Improvement Company and Portneuf-Marsh Valley Irrigation Company to the then-impressive tune of $250,000. The booklet featured photos of the young but growing burg and included overly enthusiastic promotional predictions for Downey’s future growth and prominence, once the irrigation project opened up to water thousands of acres of new farmland. I always wanted a copy of the booklet and was disappointed when I learned that my grandparents’ copy had been cut up for a relative’s scrapbook. I have yet to find an intact copy to buy.

North of the bank was Lowe Drug. It was owned by our next door neighbors, Harry and Dorothy Allsop. Harry, the town pharmacist, was my revered scoutmaster. I think he must have been one of the most devoted and conscientious leaders the Boy Scouts of America ever produced. He also co-owned a Cessna airplane stored in a hangar at Downey’s small airport. Occasionally, he would fly our troop to Pocatello and back. It was an eye-opening and mind-boggling thrill for us young boys, who had seldom ventured far outside town, to view the world from a lofty perspective. Harry’s wife Dorothy, also a caring and delightful neighbor, once saved the five-year-old me from injury, or possibly even death, when she discovered me dangling from the Allsops’ second-story bedroom window sill while a wicked rose bush lay in wait below to impale me. My dad climbed the adjacent ladder to grab me before I plummeted to an unhappy ending. (It’s a long story.)

The Allsops’ drug store stocked a respectable supply of diecast Matchbox cars (at fifty-five cents plus two cents sales tax). I still have my personal fleet. I bought more candy there than at the grocery store. My favorite penny candies were Pixy Stix and cinnamon bears, although when I had more than just a few pennies, I opted for a caramel Sugar Daddy, which sometimes helped pull loose teeth. Occasionally, the caramel treat included collectible cards that featured exotic animals. I still have them, too: they may have activated my lifelong collector packrat gene.

After the hospital shut down in the 1980s, a domino effect devastated the drug store, and it closed shortly thereafter. It was an extremely sad day when both of those foundational institutions ceased operation. The hospital was fatally impacted when Dr. Burkett retired and moved away, and no one could be found to equal his skills and experience. It seems today’s medical educational process don’t produce general practitioners who can deliver babies, remove tonsils and appendixes, fix broken arms and legs, treat heart attacks and strokes, and attend to emergency situations like car wrecks and rural farming accidents.

Adjoining the drug store was the clothing and shoe store run by our neighbors LaVar and Dora Johnson. The store also stocked a supply of religious books and Boy Scout paraphernalia like camping gear, handbooks, merit badge booklets, and uniforms. The BSA was the central focus of many young boys’ social lives, at the time. The store was later purchased and run by Ken and Donna Williams, welcome transplants from Utah.

The last store on the east side of Main Street was Western Auto, the hardware and household goods chain store. Don and Helene Bosworth were the owners. Robert and Colleen Baker later purchased it and renamed it Baker Electric. I visited the store periodically during the summers, hoping to obtain a discarded cardboard refrigerator box. To get spending money as a young boy, I cut down and refashioned a refrigerator box into a candy stand and opened for business on the corner of our lot. Occasionally, I accepted various other methods of payment besides hard cash. I still own a highly polished gray rock that was offered in payment for a candy bar. And I still remember who conned me into that transaction. Later, my friends and I raised personal spending money by walking and biking along the highway and side roads to collect discarded soda pop and beer bottles that we redeemed at either the pool hall or the grocery store.

Lamentably, the family-owned businesses of decades ago didn’t survive to today. Downey’s current population is estimated at 633. Main Street now includes a dentist’s office, community health clinic, highway district building, post office, artist’s studio, beauty salon, fitness center, city offices, veterans’ memorial monument with a remarkable “United We Stand” mural painted by local artist Dan Lewis, a bank, and the Downey Public Library. Around the corner are a motor parts business, storage units, a mechanical repair shop, our iconic metal-clad grain elevator, a bar, and the combined city park and Bannock County Fairgrounds. The park hosts the pioneer-era Coffin family log cabin and some former CCC/Conscientious Objectors barracks, now repurposed as county fair exhibit halls.

On Center Street you’ll find an irrigation company, the historic George T. Hyde residence, the American Legion hall, a church, park, assisted living center, LDS meetinghouse, and the elementary school. Middle and high school aged students are bused a few miles north to Arimo. The Reed Hyde Memorial Airport occupies the end of Center Street. Located along the old Highway 91 entrance to Downey are two service stations with convenience stores, the highway maintenance building, the newly-constructed fire district building, an old log-cabin style service station (under restoration), an automotive repair shop, storage units, and a custom meat-cutting business. At the Downey exit off Interstate 15 sits a major truck stop with a restaurant and small motel.

Downey’s major economic and social event continues to be the pivotal and energetic Bannock County Fair and rodeo, held annually in early August.

The Downey of yesterday or today is not exactly Garrison Keillor’s Lake Wobegon, but the nearly idyllic rural lifestyle and setting make it a worthy competitor (minus the lake, of course). For me and many others, Oxford Peak and Downey still call out emotionally to our memories and hearts—but even the place where heaven and earth meet still needs a grocery store!

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only

Comments are closed.