No products in the cart.

Flatlanders

Stupid Ways, Overwhelming Numbers

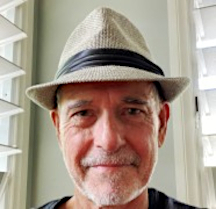

By Steve Bunk

This particular long-haired guy was newly arrived in McCall from Los Angeles, which had the risible reputation of a laid-back place. Laid back if you were from New York maybe, or Tokyo, but hardly to the early-twenties crowd slouching around the porch of Lardo Saloon & Dance Hall, across the street from Payette Lake.

Let’s call the newcomer Jake, because I barely knew him and certainly can’t pluck his real name from the entangled ecosystems of memory spanning four decades, and more important anyway is what everyone called him.

We called him a Flatlander, the same thing we called everybody else who drove against the down-rush of the Payette River up the twisty highway from Boise to the lake in the mountains.

The designation of Jake as a Flatlander was generally preceded by a salty adjective, because we were a salty bunch back then, salty and affected. But don’t worry, in this story you get the low-sodium version of our affectations.

Words were important to us. We didn’t make up many of them but we had a patois, that verbal secret handshake familiar to professionals and high-schoolers. Like any good jargon, it was a kind of shorthand. It was a bit impoverished, I suppose, but it tickled us.

We said “anyway” a lot, because it could mean all sorts of things depending on the context. We said “seriously” when we meant the opposite. We pronounced “all right” as “aw reet” (I warned you we were affected), and the second word of “you bet” was drawn out like a whole note in common time. We had a lot of other sayings that I’ll forgo in deference to finer sensibilities.

The point is that with jargon, the right word or phrase can stick your target wriggling on a pin, and Jake was a Flatlander. What more needed to be said?

He tried to be accepted. He talked up a storm, assailing us with what he hoped were engaging tales of life in L.A., in the Flatlands. He offered gifts and blandishments. He showed off his vehicle, which was long and low-slung, a Flatlander car.

We drove pickups, the older and more beat-up the better. If it had been left out in the weather for years and the paint was destroyed and the windshield cracked, then you might receive a laconic, “Nice rig.”

We folded our arms and frowned at Jake, not because he was Jake or because we thought he might go away. It was out of pride. This was our town, and we knew it was as beautiful as any to be found. We were the chosen ones, not him. He was a Flatlander who talked too much and drove a dumb rig.

When would people like him stop coming? When it was too late? When they had trashed the place with their stupid Flatlander ways and their overwhelming numbers?

Jake understood this. He knew he had lucked out to find himself in McCall in the summer of 1974. Everyone understood it. The few hundred of us working and socializing together were roughly the same age, and we all recognized it as a golden moment.

In the wider world, the hopes of the Sixties had collapsed into cynicism, war, and other unbridled behavior but in this little town we were sheltered from such cares by immersion in Nature, which was ours through good fortune, the strength of community, and the freedom of youth. It was an idyll weak on ambition, strong on fun, and not to be taken for granted. This was why we feared and loathed the Flatlander, even though we were all Flatlanders.

It’s possible that somebody in our extended group was born in McCall and could put the lie to this generalization. Some of our crowd were native Idahoans, mostly from Boise, an exalted subspecies of Flatlander. Many, like me, were originally from California.

But the good thing about the stigma of not being highland-born was how quickly one’s ostracism ended. Not overnight but in a year or so your presence was acceptable to those who had arrived a year or so before you did. It was like a parody of Deep South snobbery played out at high speed.

I now know a guy our age who was born there, but I imagine neither he nor other natives had much need of our subculture then, not having arrived a year before we did.

Red barn in a field of snow with a fence

I left McCall that fall and didn’t return until the following summer. Over each Fourth of July weekend, when vehicles streamed up the highway and the town’s population quintupled for a few days, members of our gang loitered on the log-rail porch at Lardo’s, cursing the traffic. It was a rite of passage.

A year after Jake’s arrival, there he sat on the porch, giving it to the Flatlanders for all he was worth. But these imprecations were delivered languidly. He wasn’t nearly as ticked off as he was laid back.

I had first arrived in the autumn of ’73 from Newport, Oregon, where I was living in a cabin above the ocean. One day I was down on the beach with a neighbor named Randy Clark, who was from Boise. When I mentioned that I was interested in moving to the mountains, he said, “You should go to McCall.”

He drew a map in the sand that showed Boise, the highway, Payette Lake, and McCall. Then he drew a blowup of the highway’s dogleg west when it hit downtown at the lake.

“Follow the lake’s southern frontage to the edge of town. Just before Warren Wagon Road veers north from the highway you’ll see a pizza parlor called the Brass Lamp.” He drew a square and tapped it. “Go in there and look up a guy our age named Rod Davidson. His dad owns the place. Ask Rod for a job there. And next door to the Brass Lamp is a white house, which the Davidsons also own.”

He drew another square. “Maybe you can stay in the White House, if there’s room.”

Not long after this, I followed Randy’s mud map up the highway to McCall. I went into the Brass Lamp and found Rod, who gave me a job making pizzas and “rolling dough,” flattening out the fat stuff we mixed in garbage cans by shoving it under a mechanical roller.

I shared the White House with Rod’s younger brother John, who later wrote an evocative story for this magazine about his Boise family’s long association with McCall [“At the Lakes,” January 2004].

No trace remains now of the White House or the Brass Lamp, but in those days the latter was a nexus for our crowd second only to Lardo’s, which was founded by Rod and his pal Ron Bevins. Many of us worked at one or both places.

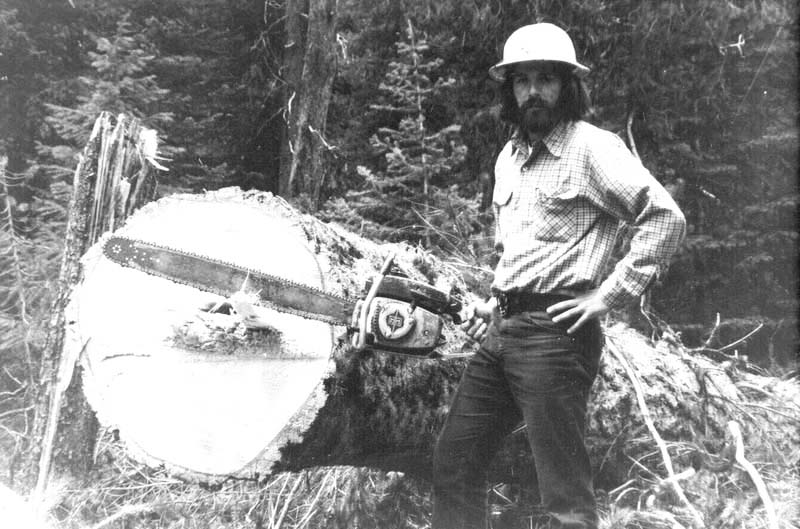

In general, the young men were bartenders, loggers, builders, and, in a few cases, fire lookouts or smokejumpers, while the young women were waitresses, worked in shops, or sometimes got jobs with the Forest Service.

My friends Kevin Bowes and Michael Bunnell soon joined me in McCall from our home town of Sacramento and we all shared the White House with John. Kevin went into construction. Michael quickly graduated from dough-rolling to manager of the Brass Lamp, a fate he regarded with horror.

We later tried our hands at semi-entrepreneurial pursuits such as splitting timber to sell as firewood, but we used axes because we didn’t have a splitter, so forget it. We shoveled snow off roofs a few times, and engaged in the dubious practice of disassembling old barns to sell the weathered wood to Boiseans for use as paneling, but those enterprises suffered from an imbalance between income and time spent on task—meaning we spent more time on roofs than was strictly necessary to get the tasks done.

When the searing monotony of rolling dough and eating pizza began to threaten my sanity, I started working as a substitute teacher at McCall-Donnelly High School, and after an English teacher got in a beef with the administration and quit, I went full-time.

I wasn’t long out of college and still recalled all the blue innuendos in Romeo and Juliet, which made my fifteen-year-old audience bug-eyed. It unnerved me the way they sat open-faced, apparently absorbing whatever I said.

A few things worked out pretty well. For example, rather than having them read famous short stories, I would tell them the plots, all except the endings, which they had to make up and write down. As you can imagine, the results would have graphed as a bell curve but the several on the right tail were a delight.

Even so, I had never taught school and felt such an imposter that when the principal offered a full slate of classes for the next year, I quit.

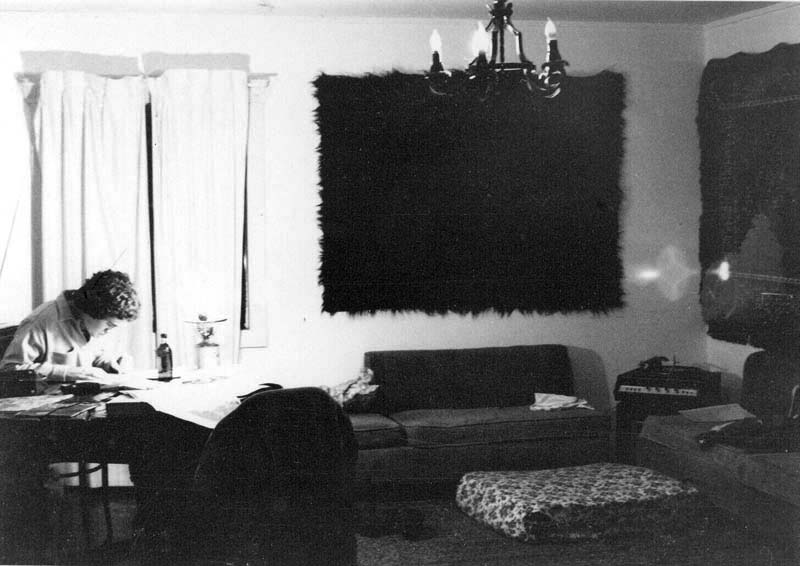

The winter of 1973 got pretty cold, down to minus twenty-three degrees, and we had arrived too late in the fall to lay in much wood for the living room stove at the White House, so we huddled around the oil heater. Nobody shoveled the walk, the snow grew past the windows, and we slid down an icy slope of several feet to the front door.

You could regard this situation either as four young guys who did nothing right or who did exactly what might be expected of four young guys from the Flatlands. Or both. Not that John hadn’t had plenty of experience in mountain living, but he was still a teenager and I somehow doubt that he could have been directed into much actual work up there as a kid. He was a dang good golfer, though.

In any case, his dad started making us pay the enormous oil bill later that winter, and then there was very little heat at all.

We spent many evenings at Lardo’s, where the ladies entered in pairs, carrying themselves as if they were mounted on the prows of ships in a headwind. The boys said all sorts of things to them, as you might imagine, and mostly they reacted benevolently, the obligation of American peerage.

Perhaps I elevate them too high, but I think at least the genders were as close to peers as stubborn patriarchy would allow. We had a few barn dances in Lardo’s, I mean to tell you. Who would have thought a pack of Deadhead Vietnam War protestors could allemande and do-si-do to beat the band?

Not that most of us listened to such stuff. We catered to the Seventies rock canon of the Doors, Dylan, the Stones and all the rest, but any such group that didn’t mind a look down a country lane, like the Band, the Allman Brothers, or the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, got our attention.

Rod and John Davidson and their little sister Laurie, who were among the McCall long-timers by virtue of their family cabin on the lake, were too smart to play the when-did-you-arrive game. They accepted us interlopers from the start and we were soon hanging around their fabulous log cabin with its own dock on a shoreline that even then was worth a pretty penny per foot.

When I think of that dock, I smile at the memory of Rod trying to learn how to roll a kayak in the lake’s still water.

“I want you guys to tip me over,” he directed as he sat in the kayak on the lake, holding a paddle, while we sat beside him on the dock, clutching what John always called our beverages. “Then I’ll try to roll. If I hold the oar straight up, that’s the signal to turn the kayak upright.”

We put down our beverages and turned him over. Then we sat down again with our beverages and watched as he thrashed wildly, coming nowhere near upright. In a river kayak your legs extend under the deck, which is why it can be difficult to escape if you get caught upside down.

After a period of time that demonstrated a remarkable ability to hold his breath even in the midst of exertion, Rod stuck the paddle upright. We turned him over and watched him gasp and splutter for a while.

We refrained from chuckling while he was upright. Rod was burly and could be hotheaded, and he was determined to do this. He caught his breath and told us to tip him over again. The process repeated itself, the oar coming up, the splutter and gasp, another inversion, another failure, Rod repeatedly defying fact like a little guy in a movie refusing to stop fighting a giant despite all his buddies yelling, “Give up!”

I remember admiring his determination, but I also remember the pleasure of a warm summer day on the dock at the lake with a beverage and no interest whatsoever in kayaking.

I did manage a bit of canoeing on the lake but was never adept at waterborne vessel sports. The arrival around then of the first water scooters, which we knew only as generic jet skis, struck us as a violation of everything right about the lake. In winter we could live with snowmobiles wherever the plowed roads stopped, because they were just about the only mode of transportation, although cross-country skiing was much preferred.

A guy named Willard, for whom the term “wiry” could have been coined, used to ski from Burgdorf to McCall and back, a total distance of sixty-two miles, but that was an achievement not replicated by any non-Willard I knew.

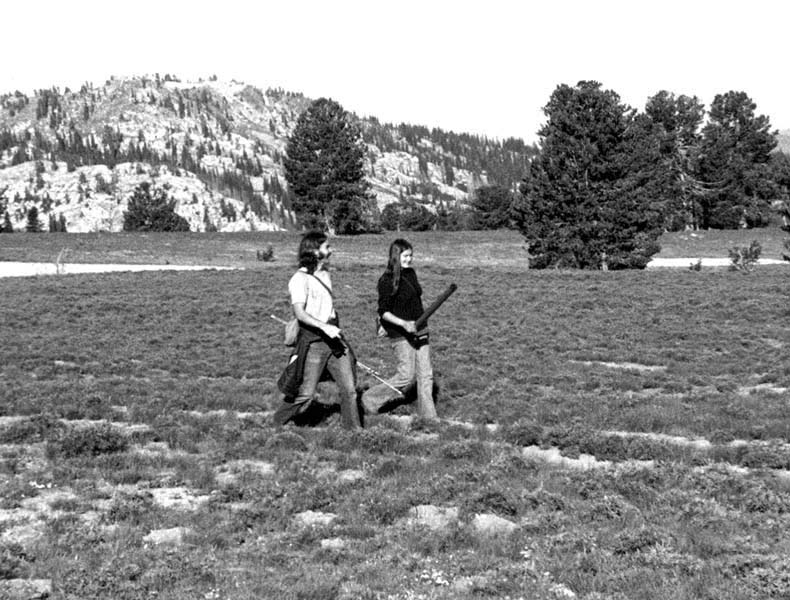

We liked to dive off the cliffs along the eastern arm of the lake, which is almost split in two by the peninsula of Ponderosa State Park. Near the inlet of the Payette River’s North Fork coming down from Upper Payette Lake, we partied on the blond sands of North Beach, where the image of a lovely girl I knew remains as clear as a photo.

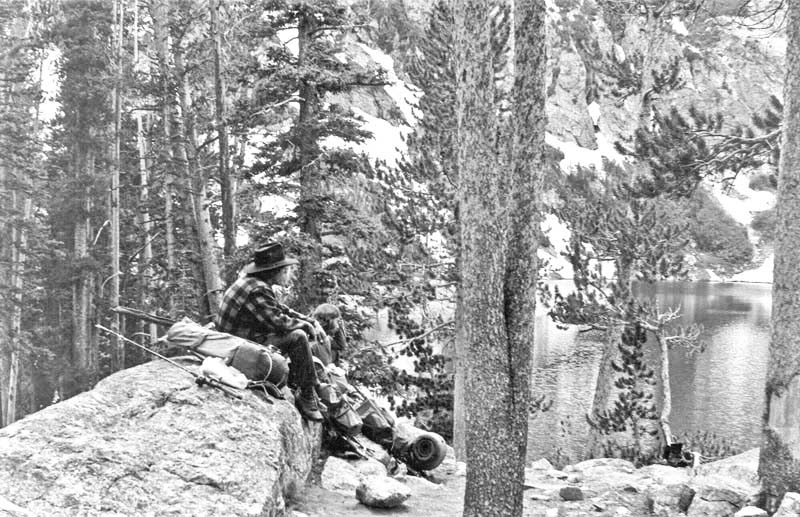

We cross-country skied and snowshoed to hot springs in meadows and on mountainsides where we sat naked under the stars, our upturned faces stung by falling snowflakes. By the time we crawled out, our arms and legs were pool noodles. We backpacked, camped, and fished just about every mountain lake in the area, sometimes reduced to scrabbling on all fours up a near-vertical forest floor to reach a peak.

We got lost and exhausted plenty of times, but also found magisterial silence, heartrending views, and trout so big you’d think they were fish stories. We saw deer, elk, eagles, beaver, otter, plenty of hawks, and the occasional bear. To me at the time, the paradox was that it all seemed both eternal and ephemeral. Probably I didn’t want it to last, at least not forever.

For some time now, reports have trickled in of deaths among the crowd. Even Rod died of sudden heart failure while fishing with Ron Bevins and another old friend. He was just sixty-one. I left out most of the characters from this account but when I see old pals from that time and place, such as Al Benton, Ron Tucker, and Kirk “Big Al” Borup, we often veer into reminiscence.

All of us have kept in touch with McCall, some never left, and others own property around there. Kevin lived in McCall for decades while he and Devon raised their four kids. For a while, people close to us who hadn’t lived there were prone to suggest that nothing could compare in our minds to the excellence of those youthful years.

Such complaints faded long ago, probably in part because the place has continued to be an incubator of good memories for us. But it’s true, those days were special, and when people who spent them together see each other now, the undercurrent of our shared history remains strong.

A few years ago, when Michael and I were driving up from Boise to his cabin in McCall, we ascended the highway’s curves through the foothills into mountains braided in tamarack and aspen above valley meadows and the mercurial river, and he remarked that whenever he took the trip and saw all this, he was gratified yet again to have made it part of his life.

Of course, everything’s different now than when he was young and carefree, but in a way I guess McCall still makes him feel something of what he felt back then. I guess that goes for all of us.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only