No products in the cart.

Gone Mad

An Old West Murder and Escape

By Ray Brooks

When I was a youngster in 1963, my family was inspired by the incredible antique bottle collection of our neighbor, Whitey Hirschman. He had lived in Fallon, Nevada, where he had been part of collector’s club that dug up a lot of 1860s-vintage bottles at historic Virginia City, Nevada. Whitey owned a saloon in Ketchum where many of the artifacts he collected are still displayed. We had plenty of old mining areas to explore near Ketchum, and with instructions on how to dig for pre-1900 bottles from Whitey and another mentor, I had a new hobby. To a young teenager, it seemed the next best thing to hunting for gold, and it had a much higher probability of success.

That summer we had a visit from my brother’s college roommate, Bob Caski, with whom we dug for bottles at a high mine near Hailey. Bob, whose family lived near Mackay, had already dug some 1890s bottles at the one-time town of Houston, just south of Mackay. His mother was pressuring him to give them to someone before she hauled them to the dump.

I was aware of Houston from a sixth-grade Idaho history class, because it was the major town in the Lost River Valley in the 1890s. Soon, I was the happy recipient of about twenty of Bob’s Houston bottles, and I’ve managed to hang onto a few for the last fifty-nine years. Most of the five hundred or so bottles our family found in the mid-1960s have been sold or given away but I still have a few of the best. By the time I went off to college, I was done digging for bottles, which is an incredible amount of work and is now illegal on public lands. I cherished those ancient Idaho bottles we had retrieved with so much effort and, happily, my parents never hauled them to the county dump, which I suspect is the fate of many Idaho artifact collections.

Although I don’t take anything home from old mines these days other than an occasional mineral specimen, my interest in Idaho mining history has turned into a retirement occupation. This winter, while perusing my 1950 edition of George McLeod’s History of Blaine and Alturas Counties, Idaho, I noticed a short newspaper article about a 1895 escape from Hailey’s Blaine County Jail. It inspired me to start an internet search of the Library of Congress’s digital collection of old Idaho newspapers. After a few hours, I found most of the rest of the story, which amounts to an enduring Idaho mystery.

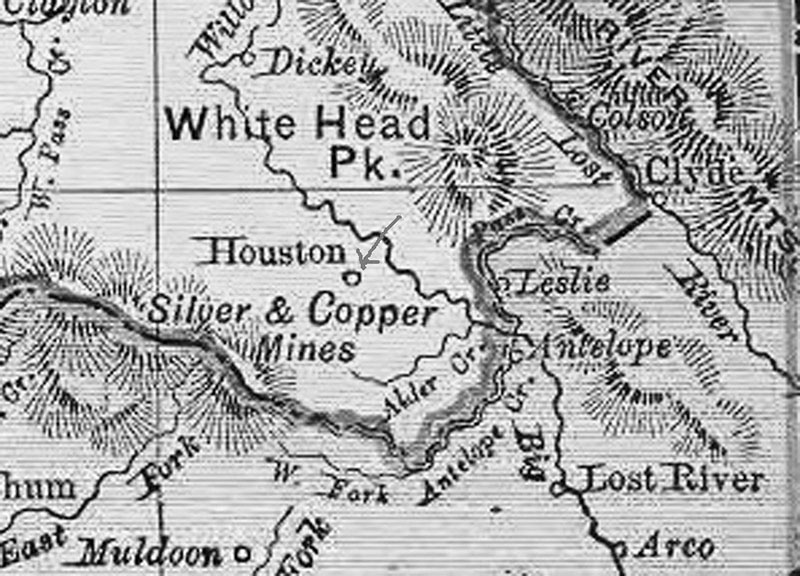

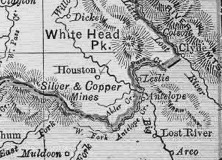

This 1895 map shows Houston. Courtesy Ray Brooks.

Houston, 1890s. South Custer County Historical Society.

Blaine County Courthouse, jail, and Alturus Hotel, 1907. Courtesy Ray Brooks.

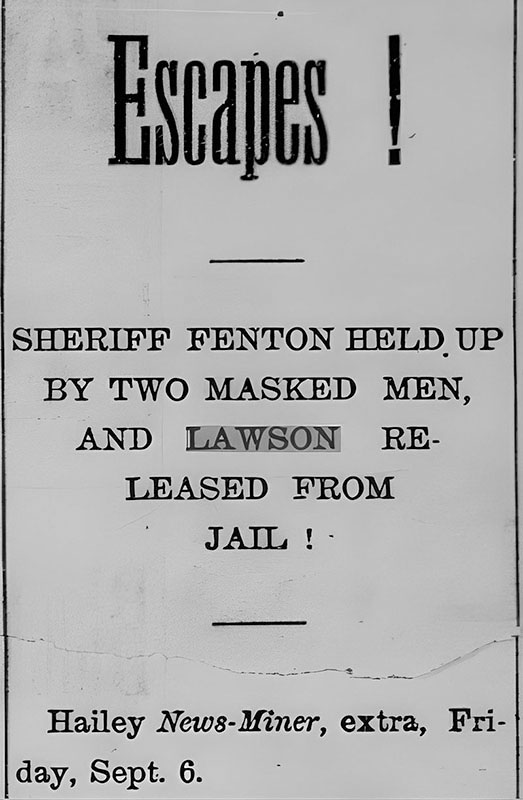

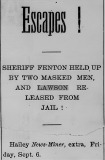

Headline of Lawson's escape, 1895. Courtesy Ray Brooks.

Houston school, 1890. Courtesy Karen McKelvey Hames.

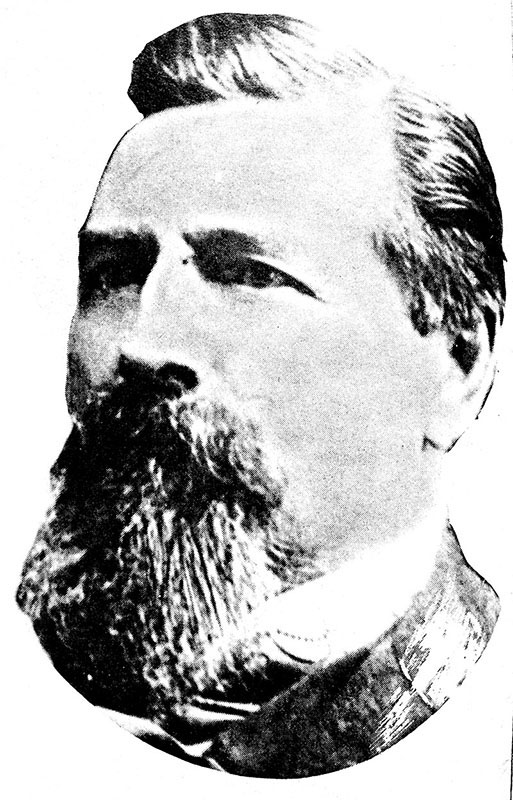

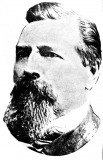

Paul Lawson 1893. ISHS.

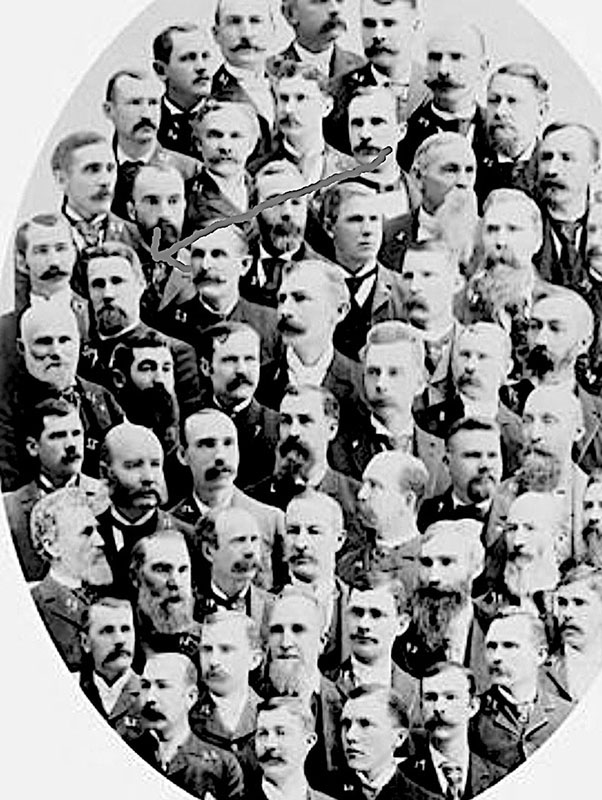

Arrow points to Lawson in 1893 Idaho Legislature. ISHS.

Circa 1890s bottles collected from Houston. Ray Brooks photo.

The Challis Silver Messenger’s May 21, 1895 issue explains the details of the murder of George Watson by Paul P. Lawson in the central Idaho town of Houston. In addition to the particulars that he was sixty years old, five-foot-nine, and weighed 225 pounds, Paul Lawson was a rancher, an ex-Idaho legislator, and a respected man in central Idaho. Before he killed George Watson in Houston there was bad blood between them but it might be that what led a decent man like Lawson to commit murder was temporary insanity.

George Watson, who was described as a large and strong man, showed up in 1894 in the thriving mining and ranch supply town of Houston on Big Lost River, three miles southwest of where Mackay would later be established. Watson soon married a young widow who lived in Houston. During an argument over the custody of her child, who had been living with the widow’s parents, the first unfriendly encounter occurred between George Watson and Paul Lawson. Lawson pointed a shotgun at Watson and ordered him to leave the premises without the child. A month later, the two men met on a street in Houston and Watson knocked him down. In what was described as “a rough and tumble fight,” he kicked Lawson in the face. Lawson’s teenaged son heard the fighting, grabbed a gun, and took two shots at Watson without hitting him, but that ended the short altercation. Lawson had “sundry bruises about the face and head.” His son fled to Montana ahead of an arrest warrant, but returned to Houston in 1895.

On May 15, 1895, Watson was walking down a road beside the home of the Miller family, a half-mile below Houston, when Lawson sprang from the house with a double-barreled shotgun loaded with buckshot and slugs. He shot Watson in the back, knocking him down. Watson regained his feet, exclaimed, “You murderous SOB,” and ran away. As he was climbing over a nearby fence, Lawson shot him in the back again, and his victim soon expired.

Lawson was so agitated that he stood guard over Watson’s body for fourteen hours, allowing no one to touch him, cursing all who tried. His friends attempted to justify the murder but Lawson was arrested the next day by the Custer County sheriff, who had ridden fifty-seven miles from Challis.

At Lawson’s murder trial in Challis on June 14, 1895, he freely admitted to the deed but nevertheless pleaded not guilty. The Messenger reported: “It appears that Lawson has been upon Watson’s trail ever since last November with a rifle or shotgun, and on May 14, Lawson imagined that Watson was about to leave the county and he followed him for some distance with a shotgun, as was testified to by himself and others. But on the next day, Watson returned and was in the public highway nearly opposite the Miller place, unarmed, when Lawson shot him down in a most cowardly manner.”

On June 18, 1895, Lawson was convicted of murder in the first-degree and was sentenced to death by hanging on July 26, the first death sentence in Custer County’s fourteen-year history.

The June 29, 1895 edition of the Ketchum Keystone newspaper noted that Sheriff Hosford of Challis visited Ketchum the day before, en route to the jail at Hailey’s Blaine County Courthouse, with Lawson in his custody, “the jail at Challis not being deemed sufficiently safe to hold the prisoner.”

Although he had been sentenced to hang, legal appeals kept him in the secure Blaine County Jail until September 6. Because of Lawson’s advanced age and status in the community, he was allowed to spend days and evenings in a locked corridor at the jail, furnished with a table and chair, where he wrote letters to the outside world, which apparently were not examined by the sheriff. At 10 p.m. on September 6, Sheriff Fenton was about to unlock the courthouse door that led down to the basement jail and lock Lawson in his cell for the night when two armed men thrust pistols in his face. They confiscated his keys and led him to the cell that awaited Lawson, thrust him inside it, locked the door, and dashed out with the prisoner. A third accomplice waited outside with four horses, and the four men made a clean escape.

Although Sheriff Fenton created sufficient noise to soon be released, by the time he assembled a posse, there was no finding the escapee and his cronies. Wanted notices and rewards were notably lacking from Custer County officials, but Idaho state personnel soon offered a $2,500 reward for the apprehension of Paul Lawson and his three fellow desperados.

The editor of the Messenger was at his satirical best when he described Lawson’s escape. “Lost, strayed, or stolen: one Paul Lawson from the Blaine County Jail, costing Custer County over five thousand dollars. Anybody knowing the whereabouts of said Paul P. Lawson will please return him to the Blaine County Sheriff, who was too kind to the harmless (?) old murderer.”

Rumors of Paul Lawson’s whereabouts were often printed in the Challis newspaper. First, it was said that he and two younger men had been encountered twenty miles north of Weiser on October 14 by a couple of woodcutters. Then he was rumored to be hiding in the Seven Devils Mountains, and then in Mexico. In February 1896, the lawman who had allowed his escape showed up in Challis. He was no longer the sheriff of Blaine County, but was still a deputy sheriff. He asserted that Lawson had been located in Mexico, and the rumor went around Challis that the deputy was there to collect the papers necessary for him to seek Lawson’s arrest across the border.

In June 1897, the Messenger reprinted an article from Boise’s Idaho Democrat newspaper that asserted Lawson had taken passage to Cuba and was now a colonel in a regiment of Texas and Idaho cowboys who were fighting with Cuban revolutionaries against Spain. “He now is titled Colonel Paulia Pai D’Lausanea, and when Cuba is freed, he will be their minister to the United States,” the account declared. My research showed that although Cuba was liberated in what became the Spanish American War, the US was not officially involved until April 1898, and I found no mention of Colonel Paulia Pai D’Lausanea or Paul Lawson in that war or later. Even so, perhaps he did perish during Cuba’s liberation by United States forces. Yellow fever and other diseases of the time, as well as Spanish bullets, killed many people.

The April 5, 1897 issue of the Messenger reported a court hearing for Paul Lawson for a mortgage default on a loan for $1,100. The property in default was not described, but it was likely Lawson’s ranch near Houston. That town continued to boom until 1901, when the Oregon Short Line railroad opened a station three miles away. It was named Mackay for mining financier John Mackay, who had just bought numerous nearby mines and who arranged for the railway to build a line across the desert from Blackfoot. The two stores, restaurant, boarding house, four saloons, and Methodist church in Houston soon moved to Mackay, and Houston joined the ranks of Idaho ghost towns.

I searched Idaho newspaper archives in the Library of Congress all the way up to 1925, when Paul Lawson would have been in his nineties, but found no further mention of his rumored whereabouts. However, I did turn up this tidbit in an October 1905 edition of the Messenger: “Frank Clements was arrested in Mackay for rustling thirty horses in the Island Park area. In court, he mentioned he was paid two thousand dollars ten years ago to help Lawson escape the Blaine County Jail.” A search of folks interred in the Houston Cemetery does not show any Lawsons, but the remains of George Watson rest there. Thus, Paul P. Lawson enters Wild West history as an escaped murderer who thwarted justice.

After I completed writing the above, I conducted a final internet search for any historical details I might have missed. Eureka! Someone else had found the story of Paul Lawson worth writing about. I located a slightly expensive, mildewed copy of the July 1965 issue of Frontier Times at an online sales site. Frontier Times featured Old West tales, and in “Riding the Shale Rock Trail,” a writer told the story of two young Nevada cowboys who in 1895 searched for a stolen stagecoach strongbox in what is now Craters of the Moon National Monument. After giving up that search, they were arrested by a sheriff’s posse near Hailey and endured a short stay in the same jail where Paul Lawson was incarcerated. The cowboys were soon deemed harmless and released.

The author then moved into Lawson’s story, which differed slightly from what newspapers had reported. He contended that Lawson and the man he murdered both pursued a relationship with a “Brazilian trollop” who lived in Ketchum, which was the closest large town to Houston. But his story then drifted from published facts. On the other hand, he provided a photo of Paul Lawson during his service in the 1893 Idaho Legislature, which he credited to the Idaho Historical Society. Interestingly, he contended that after Lawson’s escape, the Nevada cowboys guided him to Gooding’s City of Rocks for an initial hideout. They later conducted him across the Owyhee Desert and on to Nevada, which is as far as that writer took us. Coupled with what I discovered, it is perhaps as far as the saga of Paul P. Lawson can go.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only

Comments are closed.