No products in the cart.

Hells Canyon Revival

By CMarie Furhman

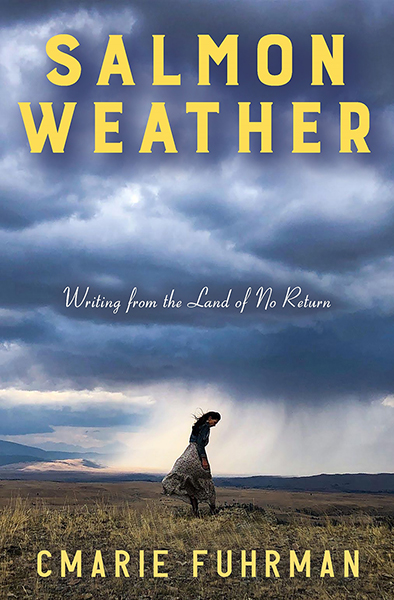

Following is an excerpt from a chapter in the author’s new book, Salmon Weather: Writing from the Land of No Return, used with permission.

And always, in this search, a person might find that she is already there, at the center of the world. It may be a broken world, but it is glorious nonetheless.—Linda Hogan

Our task is to enter the dream of Nature and interpret the symbols. —E.L. Grant Watson

This canyon does not abide a trail.

The steepness of its walls, and the scree that covers them, suggests a downward movement. But we are going up. Up toward the base of massive limestone cliffs.

The dogs have an easier time of it. My partner Caleb and I scramble and slide, reaching for sage and ninebark as handholds. What trails exist are likely made by deer and elk coming down from their ridgetop refuges to drink from Allison Creek. I make my way to a flat section and catch my breath. From here, it is a matter of guesswork. The way to Redfish Cave is not marked. It is not on a map. The entrance cannot be seen from below. Rumor and vague directions are our guides. Two false starts lead us nowhere; on the third, we walk a narrow precipice, squeeze through mountain mahogany, and find ourselves at the entrance.

I wrap my fingers around the steel bars that are cemented into the mouth of the cave and press my face into the darkness, eyes searching as if for a prisoner who might walk into view. The day is cool and rainy, the metal cold against my face. When my eyes finally adjust, I see it. At the far end of the entrance to Redfish Cave, in an area called the twilight zone, an ochre pictograph of a salmon.

The air escaping the cave smells like the earth when rain first touches it. Petrichor. My eyes become adjusted to the darkness, and I see the fine soil, cave dust, and the loose rocks and leaves that cover the floor. I am eager to go in. Desperate to sit in the place where the artist sat.To look closely at the dots, each no bigger than a fingerprint, in the form of a salmon. I want to touch those fingerprints, made of blood and plant as if I could touch the past, as if I can somehow connect to a history I carry in my blood. An ache to connect with this Plateau artist moves my fingers toward the art. I reach out to the salmon, my arm a bridge over which only my understanding passes, stopping short of the colored and cold cavern wall.[/private]

We carefully make our way down from Redfish Cave, down Allison Creek, and finally to the Snake River, to the murky, dam-stilled waters.When we reach the reservoir, the salmon takes over my thoughts. The pictograph is about a quarter mile above the channel where the Snake River once flowed free. For hundreds, probably thousands of years, this canyon was home to Nez Perce. Now it is a national recreation area and designated wilderness. The recent titles provide protection for the area and places like Redfish Cave but came after the river’s damming and the subsequent burial of similar sites, other art. Nearly all traces of indigenous occupation are buried under two hundred feet of water and layers of silt and debris. Salmon have not swum these waters since 1967.

From 1956 through 1967, three dams were built in succession along this part of the Snake: Brownlee, Oxbow, and Hells Canyon. Idaho Power, the company commissioned to build them, agreed to create and maintain a viable way in which salmon and steelhead would be able to bypass the dams and continue their natural migration to their natal waters, some as far as three hundred miles upstream.

In the fall of 1958, near the completion of the Oxbow Dam, the attempt to trap and transport the salmon fifteen miles upriver past Brownlee Dam, failed. Four thousand fish died in splash pools below the dam and seven thousand more in transport. Eleven thousand salmon. Two and a half times the human population of the town I live in.

Arrowleaf balsamroot at Hells Canyon. BLM.

Big Bar, Hells Canyon. Jascha Zeitlin, CC-by2.0.

Hells Canyon Dam. Wikimedia Commons.

Deer in the canyon. BLM.

The river and canyon on a 1935 postcard. Water Archives.

The book's cover. Courtesy Columbia State University Press.

Seven Devils Mountains. Wikimedia Commons.

The disaster, dubbed the Oxbow Incident, resulted in a federal investigation, but no successful remedy could be found, outside a promise by Idaho Power for a handful of hatcheries. At Hells Canyon Dam, no attempt at all was made for fish passage. In 1967, when the entire three-dam project was completed, thousands of years of salmon migration ended. The Snake River had seen its last run. The only salmon remaining above Hells Canyon Dam is painted in Redfish Cave.

Caleb and I return to Hells Canyon every spring. Escaping the deep snow at our cabin in McCall, we embrace spring at this lower elevation. Trailing our camper behind the truck, we exchange our dichromatic backdrop of pine green and white for one painted with yellow arrowleaf, pink cherry blossoms, and bluebird song. Our camp is alive with sound and color. Parked next to the reservoir that serves as the border between Idaho and Oregon, we slip our canoe into the Snake and paddle across the water, then hike up Spring Creek, where we eventually gain a ridgetop.

From our perch on the canyon wall, we barely make out the green dot that is our canoe. Around and above us, an endless panorama of buckskin and blue. Across the river, we can see the nine thousand-foot peaks of the Seven Devils, and behind us are the two million acres of the Wallowa–Whitman National Forest. Our feet rest on a ledge, soles facing the deepest gorge in the United States and thirty-six miles of a reservoir. We eat lunch among wolf tracks and elk droppings. I pull out my notebook and try to capture, in a few words, the vastness of it all. But, like the camera lens, it is impossible to frame it. I cross out what I have written and pocket the notebook. Cumulus clouds pile in from the south, and the air darkens and tosses the dogs’ ears. We hike back down to the canoe moments ahead of the rain.

That evening, I lie in bed and stare out across the water to a knob of land we have named Bone Island. It’s not fair to call it an island as it is part of the bar that the dams have stranded. It is also unfair to give it such an ominous name, but there is a lot of unfair naming in this region. The name Hells Canyon, for example, is undoubtedly not apropos for an area that holds so much beauty, so much life. The Seven Devils that guard the canyon may seem wicked to those who attempt their summits, but the name belies their Teton-like grandeur. Who chose these names and why? How do we begin to explain the complexity and exquisiteness of such a landscape with just a name? What did first people of this landscape call the bony prominences that hold the last light of evening? What words explained this canyon to them? I think of how I might rename it and falter, tripped by my need to tell everything I know about the canyon in a couple of words. Frustrated with the task, I roll over and go to sleep.

We wake to rain falling on the metal roof, so I decide to stay in the camper and write. Outside, geese honk and make their loud landings onto the murky water. Swans float by. Ducks call from the shore of the island. Inside, I make little progress.

Like before, on the ridge, I discard lines as soon as they are written. I have a poem in mind, a piece that I can see and sense, but I cannot bring it to paper. The words feel forced, planned. Rather than giving the image control, in this case, the river’s image, I try to control it. Force it into my own idea, tossing in erudition and clever enjambment so that before it is fully born, I have pushed it back into the dark. The aluminum roof thrums with the rain. I put away my writing, reach for a poetry anthology, and thumb the pages for inspiration. Instead, I find myself analyzing techniques.

I pace the short length of the camper, reading aloud. Midway through a Wallace Stevens poem, I close the book and trade it for a thick volume of theory. I hope that by understanding the construction, methods, and terminology used to make poetry, I will find the instruction I need to complete the poem. I am searching for a formula, a blueprint. I look at the lines I have written; they’re solid, intelligent, and fit the definition of a poem, but they are flat on the page. The piece lacks heart, lacks wildness, is given over to too much management. Outside, the rain trembles the dammed waters, gentle thunder echoes through the canyon. I put the poems and books away and pull on my raincoat. We will drive to the end of the road. We will go to the dam itself.

Parked beneath the dam, the windshield wipers work to clear our view while we stare at the massive cement wall that holds back the Snake River. A single outlet is open, spewing water 150 feet before it crashes into the pool beneath. From here, the dam appears as both a castle and a prison. Wires running from the parapet could as easily be gossamer as razor, yet they are neither, merely cables carrying as much as 391 megawatts of electricity. I cannot comprehend how much power that is or how the river was managed to create it. But I can see the art in the craftsmanship of the dam—the almost impossibility of it. And I am aware this art, this feat of engineering, was championed as a source of renewable energy. It is genius, and it is deadly, and I am unable to forget the cost of this structure: the thousands of salmon that died, the drowned cultural history, the river’s freedom. It is true that I have become dependent on electricity, on this structure, but true also that I depend on wildness to power my imagination. As the sun breaks from the clouds, rainbows rise from the mist of cascading water. This very place is both the end of the line for spawning salmon and the source of energy that lights our home. Across the river, a mountain goat ascends the steep canyon wall. A snow-white kid follows at her hooves. Idaho has the cheapest power in the United States.

Nez Perce, unlike many other tribes, did not rely on specific drawings for communication. When they painted, it was spontaneous, unplanned, and often unexplained to even the closest family members. The meaning of the art in the cave would always be left open to the interpreter to guess at, dream about, and wonder at. Since learning this, I have given up trying to find meaning for what I see on the smooth wall of Redfish Cave, and instead, I let the art move my emotions. I allow the art to be as the artist felt when making it. In doing so, I am allowed an intimacy with the artist that is uninhibited by contemporary knowledge. This I find the most inspiring. The most like nature itself.

Archibald Ritchie and Dave Eckles, early settlers to the Hells Canyon area, planted an orchard and extensive gardens on Big Bar, where we are camped and where the two are now buried. The Eckles Ranch, as it was called, provided most of the fruit and vegetables to the mining camps in the Seven Devils and the surrounding area. Their trees still line the terraces that serve as the campground. The trees that have survived now provide refreshment in the summer when temperatures in the canyon rise well above ninety degrees. A sign, placed by the Forest Service, explains the men’s history and the ranch in detail. No mention is made of the people who lived here before Ritchie and Eckles. To learn the Native history of Big Bar, one must do her own research.

Pre-dam photographs show Big Bar as a grassy, meadow-like slope, where archaeologists found tools and hunting implements suggesting hundreds of years of Indian encampment. From places like Big Bar and throughout the drainage, it is presumed that Native people fished for salmon and hunted deer, elk, and mountain goats. Walking Big Bar, Caleb and I have admired the hollows of pit houses, but most art, shelters, and other leavings were destroyed, collected, or now lie under the turbid water. The archaeologists’ reports, black and white photos, and the artifacts they found are locked away in a steel cabinet in urban offices throughout Idaho and Oregon. I can’t help seeing the irony in this as well. Why not just leave the items where they lie and let the water cover them? Why does the government presume the right to possess the arrowheads and tattered parfleches? Shouldn’t they belong to the descendants of this region? I know I am not the first to ask this.

CMarie Fuhrman’s Salmon Weather: Writing from the Land of No Return (Columbia State University Press, 2025) can be purchased at www.cup.columbia.edu and elsewhere online, or wherever good books are sold. [/private]

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only