No products in the cart.

Hem Abides

In the Valley of Memorabilia

By Diane Covington-Carter

My two journalism assignments when I traveled from my home in California to the Wood River Valley not long ago were the vibrant local food scene and the area’s year-round attractions. I had a vague recollection that Ernest Hemingway had lived in the area but I wasn’t there to write about him. As I was interviewing the assistant manager of an inn, she mentioned that the famous writer’s grave was nearby. “People leave all sorts of gifts,” she said. “Whiskey bottles, cigars, flowers.”

I had never paid that much attention to Hemingway. When he took his own life in 1961, I was in junior high school. I read The Old Man and the Sea in high school and dutifully turned in my book report. Years later, I read A Moveable Feast, about his early years in Paris, where he wrote in an unheated hotel room each day, away from his wife and young child. He mentioned that he always left off his writing with a clear place to begin again the next day, which was a tip I incorporated into my writing routine.

As I explored the town of Ketchum and the nearby Sun Valley Resort, I felt a bit stunned to discover just how much Hemingway lives on there in the local psyche. It is as if he haunts the area, but in a gentle way, remembered and beloved for the years that he lived and worked there. It was as if I could feel him there, and I got drawn in.

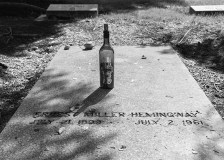

Hemingway's grave in the Wood River Valley. Frank

Schulenburg.

One of Hem's old watering holes in Ketchum. Frank Schulenburg.

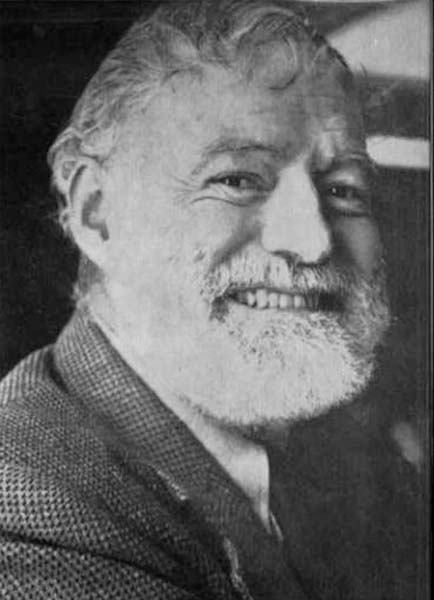

The author later in life. TonyTone.

Hemingway finished writing this novel in Idaho. Amazon.

It seemed like I encountered reminders of Hemingway everywhere I went. In the Community Library in Ketchum, I entered rooms dedicated to his memory, filled with photographs, books, and correspondence. His former home, which is private, is managed by the library, which conducts a Writers in Residence program and seminars there. On the internet, I saw the inside of his house, which looks just as it did when Hemingway and his wife Mary lived there: pictures on the walls, a hat on a shelf, clothes hanging in the closets.

I learned that a local museum also honors him. And of course there’s his beautiful memorial, just outside town along the highway, which has a bench for contemplation beside a meandering stream. When I went to his grave in the Ketchum Cemetery, it was covered in snow, but online I saw some of the gifts that had been left there for him. One note read, “The world breaks everyone.”

At the Sun Valley Lodge, where I was researching a restaurant and spa for my assignment, photos of Hemingway and other celebrities adorned the hallways. Hem sat dining with friends and celebrities and worked at his Royal typewriter. He completed For Whom the Bell Tolls in Room 206 and I visited the hotel’s second-floor “Celebrity Suite” devoted to his memory, filled with photos and a Royal typewriter.

All these reminders around me of Hemingway inspired me to learn more about him. He won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1953 and the following year was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for what the committee described as, “his mastery of the art of narrative, most recently demonstrated in The Old Man and the Sea, and for the influence that he has exerted on contemporary style.”

Then writer’s block seized him. He had achieved the highest honors as a writer and yet he couldn’t write. Most writers know what it feels like to face a blank page or blank computer screen, praying that the words will come. Can I do it this time? Is it over for me? I wish someone could have reached out and said, “It’s all right, you’ll be okay. You’re a brilliant writer and you have more to say. Don’t give up. Find peace and solace in the wild and beautiful landscape you so love here. And let people love you, because they do.”

But no one could convince him not to give up.

I remember 1961. I don’t remember anyone talking about emotional problems, going to counseling, or worrying much about alcohol consumption. Mental illness and depression were treated with shock treatments at mental hospitals. When Hemingway was twenty-nine, his own father took his life and he wrote that he felt devastated by that loss. Five of his other family members also died by suicide, including his sister and brother. We now know that Hemingway suffered from severe depression, paranoid delusions, and bipolar disease worsened by alcoholism. He also had hemochromatosis, a genetic disease that can cause fatigue and memory loss. He had returned to Ketchum from shock treatments in a mental hospital just days before he shot himself. He was almost sixty-two.

His own words, written as a eulogy to a dear friend lost in a hunting accident in Sun Valley in 1939, are inscribed on the Hemingway Memorial in the wide-open spaces he treasured: “Best of all he loved the fall…”

Perhaps he didn’t know at the end how much his life mattered to others. Maybe he didn’t know how much he’d be missed.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only

One Response to Hem Abides

Pingback: Member News | Bay Area Travel Writers