No products in the cart.

Here I Am

Battling through Polio

By Jane Falk Oppenheimer as told to Arthur “Skip” Oppenheimer

Photos courtesy of the Oppenheimer family.

This story is offered to readers free in its entirety.

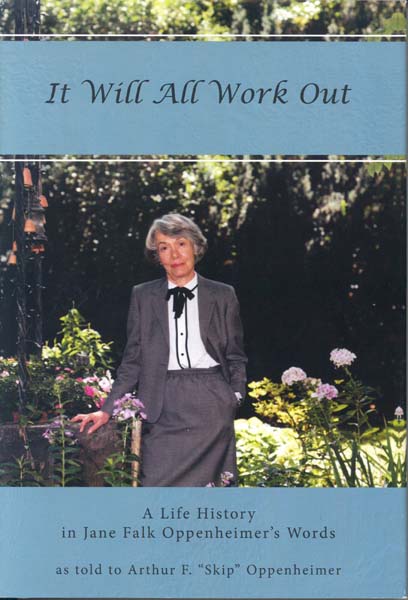

The prominent business ventures and charitable work of the Oppenheimer family have long played significant roles in the life of Boise and, consequently, of Idaho. The family’s doyenne, Jane Falk Oppenheimer (1918-2010), led what many might consider to be a charmed life of public service, family, and travel. Yet in a 2012 book of her reminiscences, told to her son, Arthur “Skip” Oppenheimer, she recounts a harrowing personal battle with polio in 1934. A 2005 study in Annals of the Association of American Geographers shows that from 1910 until the release of the polio vaccine in 1955, about 539,000 cases of polio were reported in the U.S. Idaho recorded 2,588 cases. In the following excerpts, reprinted with permission from It Will All Work Out: A Life History in Jane Falk Oppenheimer’s Words, her son introduces the story of her illness and Jane tells the rest.

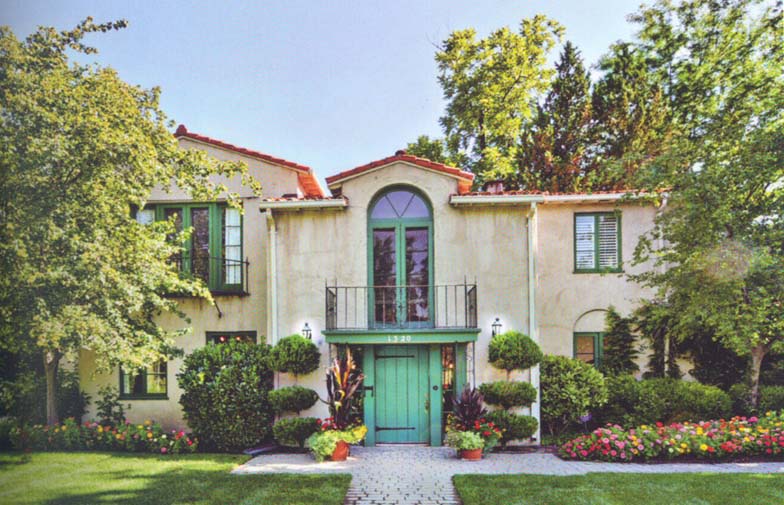

On April 6, 2002, I sat down with my mother in the beautiful light-flooded sunroom of her home on Warm Springs Avenue in Boise, armed with my voice recorder, to begin a journey that led to this book.

She looked at me with her quizzical and mischievous smile that made one feel like something significant was coming next, and said, “This isn’t going to work. I really don’t have anything to say. And what’s more, I don’t like talking into those little recording machines.”

I appealed: “Mom, let’s just give it a try.” She said she really wasn’t comfortable and that maybe we should just forget it. I said. “Let’s give it a shot.”

I cannot remember what the first question was, but I posed it andhanded her the voice recorder. The next thing I knew, the machine was making the buzzing sound at the end of that fifteen-minute tape. I never got a chance to ask the next question.

I looked at my mother and said, “I don’t think we are going to have a lot of trouble with this, Mom.”

* * * * *

What we had in mind wasn’t a precise historical document. It was a personal story relating to a dynamic span of history, and a family’s journey through that era. Both of our parents were engaged with every aspect of the periods they lived in. Between them, they met everybody from Charles Lindbergh, to Pope Pius XII, to presidents of the United States and other countries, to any number of important political and cultural figures throughout the 20th Century.

* * * * *

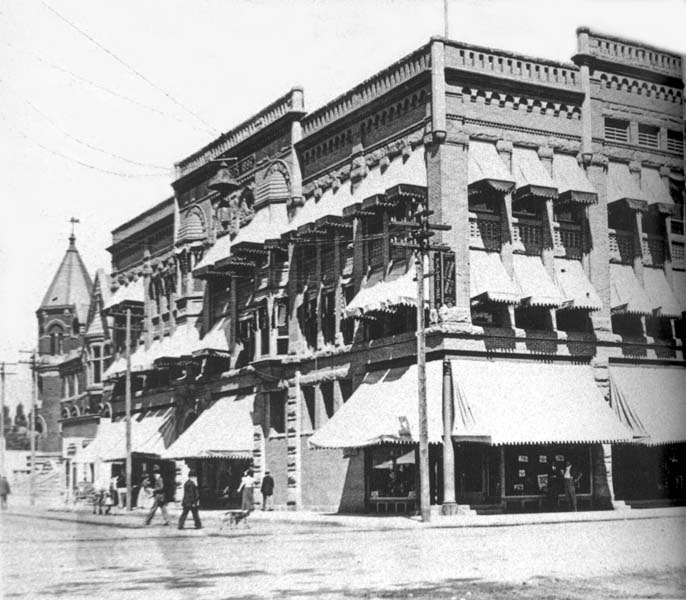

It’s amazing how few people know about [Jane’s] father, Leo J. Falk, and the huge impact he had. He was the force behind projects that were key to the growth and development of Boise, such as the Owyhee Hotel and the Egyptian Theater, and he helped immensely in bringing the Union Pacific mainline to Boise in 1925.

* * * * *

I’ve often wondered if the fact that she had polio at the very impressionable age of sixteen helped to shape the course of her life. Think of all the normal trials and tribulations that someone undergoes at that age. In her case, she was literally in confinement—in a cast—for a year. But she never dwelled on that. It’s not like she didn’t talk about it, or didn’t want to, but it never defined her. It was another chapter, and somehow, she seemed to come out of it with a heightened confidence.

What was Boise High like?

I loved it, and I was doing great. Then I had pneumonia, and so I may have been in a weakened condition. Then, that same year, I got polio.That was a year out of my life.

What year was that?

I was sixteen [1934], so that was kind of a downer.

The author as a teenager.

Jane as a young woman.

The book's cover.

From left: Doug, Jane, Janie, and Skip in the 1950s.

The old Falk Bloch Building.

Jane in her garden at home, 2003.

Leo Falk with his daughters, Jane (left) and Elaine, 1922.

The Oppenheimer home on Warms Springs Avenue in Boise.

Arthur and Jane Oppenheimer, late 1990s.

Do you want to talk about that?

I’d love to talk about that. I don’t know how much to tell you. I went to a dance, and when I came home, I didn’t feel so hotsy-totsy. Then, the whole next day, I still didn’t feel so hot. My parents were having company; they cancelled that. I was in their bed, and my parents realized I was so sick. They got Uncle Ralph and took me to the hospital. I overheard them saying, “She is a very, very sick girl, and she either has spinal meningitis or infantile paralysis”—which is what they called polio—“or a very bad case of influenza.” I thought it over: Which do I want? I think influenza. Well, I didn’t have a choice, and it ended up that I had infantile paralysis, otherwise known as polio. So I went from bad to worse.

There was a big epidemic of it. Everyone in the city was in a panic, because I’d been to a dance. The person I’d gone with, Stuart Pasley, was from out of town. They had a bulletin in the paper about me every day, and they tried to keep the papers away from me. Ed Grider, who was a friend of mine from Roosevelt School—nice fellow—died of polio. He had been playing at the tennis court next to me a week before. I thought that maybe he caught it from me. Awful things like that happened.

So they called my Uncle Ralph, who was in his office, and then called in a specialist from Portland whose name was Richard Bird. Uncle Ralph really had his cute moments. He and I really liked each other, and he said about Dr. Berg, “Now, this fellow is so ugly, so don’t stare at him when he comes in. Be polite.” So in walked this fellow who was masquerading as a Greek god—the best-looking man I’d ever seen in my life. It was Uncle Ralph’s little joke. Joey Rothschild fell like a ton of bricks for Dick Berg, and she and he had a big fling, but a little bit later he married Elizabeth Eastman, who was Joey’s best friend. But those things happen.

Were you one of the first in Boise to have polio?

Well, I don’t know about that because there was an awful lot of it going around. Some dumb nurse said, so Leo [Jane’s little brother] could hear it, that I’d probably gotten it from him, because he’d had the flu the week before. You see, a lot of people had polio, and it manifested itself as a light case of the flu in some people. Leo heard me say that if I knew who gave this to me, I’d kill them. He thought he was the one who had done it. I don’t know if he remembers that, but it’s probably just as well if he doesn’t.

So were you just flat on your back?

I remember it so vividly. They put me in a total body cast except for my right arm. They discovered later that this was the exact wrong way to treat it. Then they brought me home and I was in the sun room, which was a screened porch. I couldn’t have company or anything, but Jamie Ailshie used to sneak in to see me. Dick Simonton was the doctor on the case. He was in with Uncle Ralph, and he was very attentive and very good. They gave me bromides because I couldn’t sleep at all. Then it turned out that I was allergic to bromides. I was just in bad shape.

Is this too gory? Can you handle it? Some nurse—I had nurses around the clock—would come in everyday and she’d say, “Are you happy?” I couldn’t stand her! It was a dumb question, I thought, and I’d say, “What do you think?” She never quite got it.

Eventually they decided they had to take me to Portland. The question was how to get me there. My body was in a cast. You know, it was not the kind of thing people would want to see on the train. So, my father got in touch with Union Pacific. He knew the head fellow, and they sent a private car just to get me to Portland. Belle Fisk Doolittle, who had been our nurse as children but had stayed on as a kind of second maid, went with us.

I remember this so distinctly, it’s amazing. When we got on the private train, I said, “Oh, I’ve always wanted to go on a private train! This is just the most wonderful experience I’ve ever had.” And with that, I conked out, and I don’t remember anything else about it!

I got to Portland, and they took me to Emmanuel Hospital. They had about twenty doctors on the case. I was in a coma, but not a total coma, because I was screaming a lot of the time, which was when my mother and father’s hair turned white. It really did. It was just a terrible experience for them. They didn’t know what to do, and the decisions that they had to make were just unbelievable. None of the doctors could agree, and they’d say things to my parents like, “Well, if we take her out of the cast and put her in warm water, she’ll be a vegetable all her life.”

Finally, they decided to take me out of the cast. The reason I was screaming was because there was something in the cast that was boring a hole into my spine. I still have a scar there. It was digging into me, so I was in absolute agony, but I didn’t know it because I was in a coma, so it was worse on the other people.

I had been screaming for three weeks. Then I came to, and I looked around. My father was in the room. I wanted to dictate a letter to my favorite nurse, who I called Amy. That wasn’t her name; it was just something in my dream. I dictated a letter to Mugs Eastman [a friend] saying, “Dear Mugs, I have just come back from the most wonderful trip. We went to California by way of New York.” My father always said he never had to take me anywhere, because I thought I’d been everywhere. I’d never been anyplace, but all this time that I’m suffering and screaming, I think I’m on this wonderful trip. So, you just never know.

Then I started getting better, but they said I would never walk again. But I laid down the law: I said I would not come back to Boise until I could walk, and until I could walk without a brace. Until I could walk by myself, I wouldn’t do it. I’ve been accused of being a teensy bit stubborn but they were going to keep me there for physical therapy anyway. So we took this unfurnished penthouse at the Envoy Apartments. It was a beautiful apartment with no furniture whatsoever. Bud Frank was one of the heads of the Meier and Frank Department Store, and he loaned us some dining room furniture. But you know, we weren’t trying to furnish the apartment. We had all of these wonderful therapists and doctors like Dr. Lucas and Dr. Delahunt. I was there for quite awhile until I could walk.

Were you in a lot of pain?

Well, it was no picnic. It started out as just the worst-case flu, where everything in your body hurts. But the times I was screaming, I wasn’t in any pain—I mean, I was in pain, but I didn’t know it! It’s harder often, I think, for the caregivers than it is on the person.

* * * * *

The only lasting effect is that my left leg is a little weaker than my right one. But that’s pretty minor.

When I came back to Boise—not by a private train—I handed my brace to my father, and I said, “I don’t want it. Put it in the basement. I just want to be reminded of how lucky I am.”

Did anyone else in the family get polio?

No, but the closest people to us had it—Jess and Eileen Hawley. Not a very bad case, but they took blood from the Hawleys and gave me some. They were trying everything, and there was some idea that if you had blood from somebody that had it, you’d recover. Jess always says that we are blood relatives.

Do you think that contributed to your recovery?

It was early on and before I went through all that other stuff. I think it was a combination of a lot of things. I had very good care, but it was mostly the wrong care, and then Sister Kenny, a national authority on polio, came along and said, “Don’t do anything like put her in a cast.” Who knows? I mean, they decided that was the worst thing you could do and yet, here I am.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only

One Response to Here I Am

Harold Hollis -

at

My question is for the author of this article. I was wondering if you might be a relative of Johnny Oppenheimer? You see I was a little boy who lived in Boise with my mother and grandmother (my father was in the Air Force and stationed overseas). I remember living across the street from the Oppenheimer mansion (at least it seemed like a mansion to me). Johnny was so kind to me and my sister, I have never forgotten him. He would take us to the movies, I also remember him taking us to the Boise capital. You see I have thought of Johnny through out the years with no way to contact him. I just want to let him know I have never forgotten his kindness. Thank you Johnny, your friend Harold Hollis