No products in the cart.

Inkom–Spotlight

A Place of Stories and Storytellers

By Elise Barker

The first time I saw Inkom, in 2007, I was on my way to Pocatello with my husband, Chris Elston, to look for a house. He had just gotten a job there as an engineer and we were starting a new life, far from my home in Kansas. As we drove north from Salt Lake City, I watched the landscape expectantly. I thought if I was going to move so far away from my family, at least there would be mountains.

We took a wide curve to the west on I-15, riding alongside lava rock walls. The GPS showed we were seventeen minutes to our exit. I saw mountains behind us, mountains in front of us, and mountains on either side. I looked to the valley on our left and saw farmland, scattered homes, a railway, and evidence of a river. The sun burst through wispy purple rainclouds in a buttery yellow ray, lighting up the green valley.

I now know that these mountains are the Portneuf Range, the Bannock Range, and the Pocatello Range, and the corridor between them forms the Portneuf River Canyon, but at the time it was an anonymous, picturesque landscape. The town reminded me of a village in a model train display. “The map says this is Inkom. Maybe we could live here?” I tentatively asked Chris. “It’s not that far from Pocatello,” I reasoned, trying to lay the groundwork to get my big-city Phoenix boy to consider a more rural option.

“Maybe. If it doesn’t add too much time to my commute from the site,” he answered.

I’m sure he was calculating just how much to indulge my tendency to fantasize.

As it turned out, the extra commute time was too much for Chris, and I got used to the idea of living in Pocatello. But part of me could not let go of the notion of living in Inkom. That part of me still believes that with the right kind of view, anything is bearable. Even so, the last few months of research have changed my image of Inkom significantly, giving me a richer, deeper, sometimes sadder, and yet more beautiful story to tell.

I went to Marshall Public Library in Pocatello to learn more about Inkom’s history and found a periodical titled Yester-Years In and Around Inkom that ran from March 1972 to November 1975. The first piece I read in that magazine floored me. In her opening paragraph, Necha Damron wrote, “When I first saw Inkom I was very disappointed. It was a very desolate-looking place. Sagebrush all over, after having left flowers and trees in Utah. When I saw my brother Jed’s home with the sod roof, it was even more disappointing.”

Necha was 101 when this article was published in 1972, and she was referred to as, “Yester-Years’ First Honored Old-Timer.” When she came to Inkom in 1904, rather than seeing the mountains, she saw the harsh reality of her immediate living conditions: a sod roof, no flowers, no trees. No luxuries. As I sat reading at my table in the library, I had a hard time believing that a periodical dedicated to preserving the stories of Inkom would feature such an unenthusiastic attitude so prominently. But her honesty made me a believer, so I sat at that little corner table and read every issue of Yester-Years cover to cover. The main movers and shakers of this periodical, Lena Anken Sexton, Vera Damron (Necha’s sister-in-law), and Marcell Wanner, were clearly motivated by a desire to preserve memories of the real Inkom.

Vera wrote in April 1972, “If rattlesnakes are of any use to this old world of ours, I hope I will be forgiven for the many I have sent to their untimely deaths.”

Doesn’t that quote tell you more about Vera’s personality, her language, and her values than any fact sheet about her life ever could?

The Inkom water tower. Elise Barker photo.

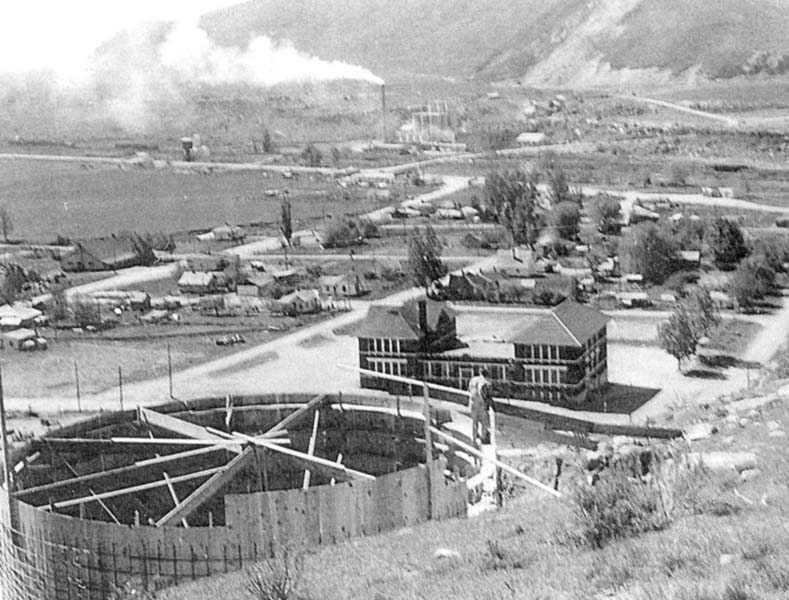

The water tank under construction, early 1950s. Courtesy of Darwin Richardson.

Thomas Ives (T.I.) Richardson. Courtesy of Darwin Richardson.

Darwin Richardson. Courtesy of Darwin Richardson.

The author and son Sam at the Inkom Cemetery. Chris Elston photo.

Interstate 15 under construction near Inkom. Courtesy of Lena Sexton.

I-15 at Inkom today. Elise Barker photo.

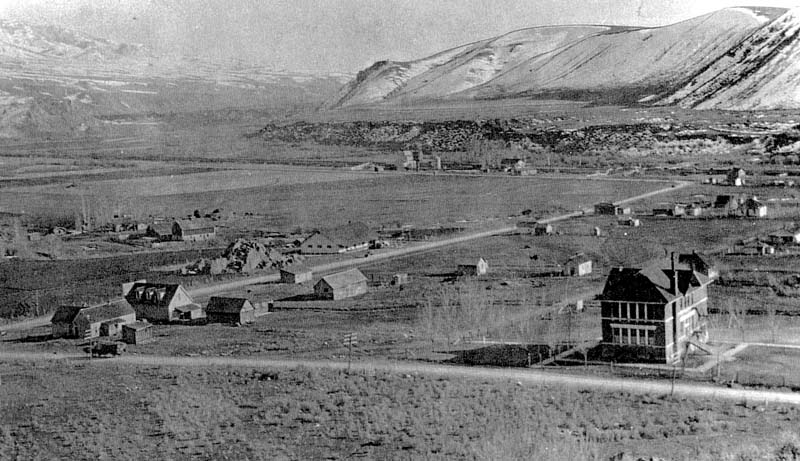

Inkom, 1926. Courtesy of Darwin Richardson.

Inkom's namesake used to be a red hare but looks like a bulldog today. Elise Barker photo.

The old service station is now the site of a home. Courtesy of Darwin Richardson.

Valley view. Elise Barker photo.

The Sorrell home, the first known abode in Inkom. Courtesy of Darwin Richardson.

View from the cemetery. Elise Barker photo.

In an August 1975 interview, Hawley Steed described himself as “a smart-alecky kid,” which he illustrated by sharing his poem about the “president of the mutual,” a Mr. Thompson, who had a white goatee: “Mr. Thompson has got the gout, no doubt, he swallowed a goat and left the tail sticking out.” Steed described his experiences as a shepherd, encountering various animals, such as bear cubs who “couldn’t jump over a quaken (sic) aspen a foot high,” and “a whole flock of blackbirds,” who “flew up and, no kidding, they hit me in the head and knocked me flatter than …” The editors deleted the rest.

Nowadays, the town’s storytelling tradition continues through a Facebook group, “Inkom Idaho Alumni and Friends,” run by brothers Darwin and Brian Richardson, in which members share stories and photos of their experiences in Inkom. The first post I saw after joining the group was by Darwin, who wrote, “I know that I am showing my age (seventy-three), but how many of you remember going to the old school for the Christmas program? Then Santa would come and give a sack of goodies to the children. The sack would contain an orange, nuts, hard candy, and other goodies. I remember when I was young, going outside after Santa arrived and trying to find Santa’s sleigh. I looked all over the place, even on the roof of the school. He could sure hide his sleigh well. Merry Christmas.”

Last December, I knocked on the door of Darwin’s home in Chubbuck. His wife Nina answered it with a warm, welcoming smile. The house was filled with family celebrating the holidays early. Kids in pajamas looked at me skeptically as they passed through the hall into the kitchen. I smelled biscuits and gravy. I had no idea I would be interrupting family holiday festivities with my interview.

“Darwin can tell you anything you want to know about Inkom, and more,” Nina assured me. “He loves to talk about Inkom.”

She showed me into his office. Darwin, who sat next to his computer, pulled up a file filled with historic digital photos of the town. He began telling me about his grandfather Thomas Ives (T. I.) Richardson, the first white settler to build a home in Pocatello. T. I. was a rancher who, at the height of his success, had a hundred bands of sheep, each band containing a thousand animals. He then had some terrible losses, but still did well financially, opening up a general store in Inkom.

In one of the Yester-Years issues, Liz Richardson recalled that T. I., who was her father, carried money in a big roll. “One day he came to my home and said, ‘Liz, I’ve just lost a hundred thousand dollars.’ I said, ‘Dad, I don’t feel one bit sorry for you, carrying all that money around. ‘No,’ he said, ‘The price of wool dropped.’”

Through it all, T. I. was famously generous. Darwin told me that when his general store closed down, “They found tens of thousands of dollars in the basement in IOUs, because people would come in and buy things on credit.”

As Darwin scanned through dozens of photos while recounting dozens of personal stories, my head began to swirl with dates, landmarks, and names of town matriarchs and patriarchs. Darwin was filled with charming personal stories from his childhood. He once was tricked into peeling buckets of potatoes for the dubious honor of trying out the new invention of the potato peeler at the old Hi-Way Inn. He told about how he would flag down the train to Poky with his brother so they could go to the movies and then play pool and ping pong at the YMCA, all for less than a dollar. Some of his stories had larger implications, such as his observation that the cement ash in the town was so dense from the local Idaho Portland Cement Plant, he would have to use a razor blade on his car windshield to chip it off. He said maybe the only good thing about that plant closing operations in 2010 was that the lava rocks around town suddenly began to look black again.

He also proved to be a wealth of historical information about Inkom, such as the school originally keeping a barn for kids who rode in on horses, and the Gathe family donating the land for the school because they thought a nearby spring made it an ideal location. Darwin wrote an autobiography that brims with such stories. Particularly poignant was his discovery of a photo of a service station owned by John Meese. As he was examining the photo, he realized that the cement foundation for the station would have been the same cement pad he played on as a kid in his backyard.

I carefully examined the photo, along with pictures of the old Hi-Way Inn and the first Inkom School, with T. I. Richardson’s homestead in the background. None of these structures still exists. The school was later turned into a wing of a church, which itself has been replaced by a new church, whose parking lot is on the site of T. I. Richardson’s old house. Similarly, Darwin heard a rumor from Jody Clark, who used to live at the dairy where the old log Sorrell house—the first house in Inkom—used to stand. Jody said the old place is still there, but it’s hidden from view, stuccoed inside another structure.

Even the story of how the town got its name reveals shifts and changes: Inkom comes from Ingacom, which is said to be a Shoshone word for “red hare,” describing a rock formation resembling a rabbit that used to overlook the town. The hare no longer has its ears, either because of a lightning storm or vandals, depending on who’s telling the story. Today it looks more like a bulldog.

Looking through the pictures and thinking about the stories, I felt deeply how transitory and impermanent human experience is. As I drove through Inkom, I saw the trees and flower beds that Necha wished for when she first came there, and I saw a concrete plant that was no longer in production. I understood the anxiety of Lena, Vera, Marcell, Darwin, and Brian about putting their stories into an enduring form while they could—because in no time, we will all be gone.

In January, while driving home north on I-15 from Lava Hot Springs to Pocatello, we hit a coyote. For a moment, I panicked, but after I took a few breaths and dismissed an anxious litany of hypotheticals, I calmed down. Looking around, I realized we had just passed a major bend in I-15 where the interstate snakes through lava rock. We were in Inkom. But at the same time, we were eerily not in Inkom. It was black, and we were surrounded by lava rocks on all sides. I could see a few twinkling lights ahead that I thought might be the old school, which is now a church, but I wasn’t sure. Cars and semi-trucks barreled past us, shaking our car. In the corridor created by the interstate, I seemed to be in a transitional space, neither fully human nor fully natural. This highway was a disruption, a terrifying impediment to creatures like the coyote in the natural flow of their lives.

All this reminded me of something Darwin had said to me a few weeks earlier: “When the freeway came through the town in the early 1960s, it literally divided the town in half.”

He told me that houses were torn down or built over, and the builders had to blast through lava rock to make room for the highway. He worked on the survey crew for that project, and, as he said, “This highway put me through college.” But the coming of the highway also, inevitably, disrupted the natural flow of the town.

When I went on a self-designed Inkom landmark scavenger hunt, I had trouble finding the town’s namesake, the “red hare” rock formation. I craned my neck around corners and tried to make random rocks around the town somehow look like a bulldog. Then, driving up Sorrell Creek Road to the water tower, I found it, but only by accident. I quickly realized why it had been so difficult to find: the highway has obscured the rock from view. You have to know where to look. You have to want to look.

Darwin, who recently moved back to the area after living in California for many years, said, “I used to be able to name everyone in every house. And their dogs. For a frame of reference I used to say, ‘Well, who are your parents?’ Now I have to say, ‘Who are your grandparents?’”

The story of Inkom is changing, and it needs young people to get inspired and involved in preserving that story. I think the Facebook group will help.

And luckily, Darwin has two sons who are willing story-keepers. Barry, who lives in Utah, is interested in family history and genealogy. Nathan, a writer and book designer who lives in Saudi Arabia, has been pestering Darwin to continue working on his autobiography. Between the first time I visited Darwin and the second, Nathan had asked his dad to write a bit about his hunting experiences as a child, which prompted him to write a couple more pages.

Darwin told me he felt cheated out of getting to know his grandpa, T. I. Richardson, but he later discovered journals that contained his grandfather’s autobiography and missionary experiences. Darwin digitally scanned and transcribed both of these works, and then had them printed in a volume for his kids. As he said, after doing this, “I felt like I really knew him.”

One night, I attended a community event, a talk given at a church about the McNabb family, who have deep pioneer roots in Inkom and in Tyhee, north of Pocatello. The potluck dinner and talk felt like it was part history lesson, part McNabb reunion. John McNabb told stories of his youth, such as how he used to milk his Uncle Bill’s cows for fifty cents a day, which made him “the richest kid on the block.” He also told stories about his grandpa, William Harrison McNabb, who headed out on his own to Washington at age twenty with a couple sets of clothes, a pistol, a banjo, and twenty dollars in his pocket. It wasn’t always easy for me to follow the names and dates, but I think what mattered the most was properly conveyed: John showed us a slice of life in Inkom. To me, the details about the pistol, the banjo, and the twenty bucks say infinitely more about John’s grandpa than a solid date would.

In an issue Yester-Years, Lena Sexton wrote, “Today little is left of the agrarian, bucolic way of life but memory. Memory is a fleeting thing. Agribusiness is the name of the game now. The small farmer is a has-been, the homesteader forgotten. Inkom’s settlement history is based on homesteading land from the Indian reservation opened for filing claims in 1902. I’d like to see every youngster in Inkom learn his local history. It needs to be cherished, as something rare and special.”

Based on the discussions within the Inkom Facebook group, the stories shared at the community event, and the narratives from my interviews with Darwin, I believe the story of Inkom is not in danger of being lost. I approached many people who said something along the lines of, “Oh, I’m not the person to talk to. You need to talk to old so-and-so.” But then these people who rated themselves as unqualified to be storytellers would reveal wonderful tales about their experiences with “old so and so.” Inkom is rich in such memories.

I went into this project as an outsider, but as I wandered the Inkom cemetery recently, I saw the names of many people whose histories had moved me and changed me. I, too, will continue to cherish and share the story of Inkom as something rare and special.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only

3 Responses to Inkom–Spotlight

Norman Rademacher -

at

My friends and I along with Darwin are researching the path of the old Oregon Short line RR. I have pictures of where it was along Marsh Creek and another friend has even more. It passed through my place. Not quite sure where yet, But Looking at satellite photos is going to help. There are places which show the evidence quite well. I often wonder as My Great Grandpa John Andrew Jackson Thornton who lived in Malad used to take the train to Pocatello. Any way My Name is Norman Rademacher I live on Marsh Creek Rd 5 miles from Inkom My email is [email protected] My dear old friend Marcell Wanner used to tell me stories about Inkom I have lots of her peoms.

Wendy Shaffer Russell -

at

I’ve lived in Inkom all my life and my dad who is almost 88 has lived in Inkom all his life. I love hearing these stories.

Lee McCormack -

at

T.I Richardson is my great grandfather. The only thing I knew about him until now was that he was a sheep rancher and pretty well to do. I also heard he went on a mission to England. I believe he purchased one of the few cars in Pocatello at that time.