No products in the cart.

Inventing Idaho

How Idaho Got Its Shape

By Keith C. Petersen

When I got a question about Richard Nixon’s profile in Idaho’s borderline, I figured it was time to write a book. I once served as Idaho’s State Historian. When I traveled around the state, one issue invariably cropped up: how did Idaho get its eccentric shape? Look at a map of the western United States. Toss out Texas and California, which entered the union under unusual circumstances, and you basically have rectangles. Congress creates state borders. Members of Congress were so vested in orderly rectangles that they gave us two virtually perfect ones in Colorado and Wyoming. Then we have Idaho. What in the world happened here?

I’d been contemplating Idaho’s borders for some time but never found inspiration to write. Then a Boise TV reporter asked, “Why does Idaho’s border with Montana look like Richard Nixon’s profile?” I thought I had heard all the border jokes—drunken surveyors getting lost and giving much of Idaho to Montana, or other states taking what they wanted, permitting Idaho only the leftovers. But I had never heard about Nixon. I now never look at an Idaho map without seeing the thirty-seventh president’s profile.

I decided to write a book about Idaho’s curious shape. It contains nothing about Nixon. But the sixth president, John Quincy Adams, became a major protagonist. That surprised me. I had never seen his name in a book about Idaho. Turns out the Gem State owes much to this man.

****

At precisely 11:00 A.M. on February 22, 1819, Luis de Onís, Spanish minister to the United States, walked toward a small house in Washington, D.C. He arrived at the spider-infested rental home of America’s secretary of state, John Quincy Adams. For two years, Onís and Adams had negotiated the futures of their respective countries. In that modest house, Onís and Adams signed a treaty that would transform North America.

John Q. Adams called the treaty signing “perhaps the most important day of my life,” quite a statement for a man who would be president. It provided borders for lands thousands of miles to the west.

Adams had a vision for America not shared by many people of his day, including his boss, President James Monroe. Monroe thought the main goal of the Adams–Onís negotiations should be acquiring Florida from Spain. Borders between American and Spanish holdings in the far-distant West interested him not at all. But Adams believed America’s extension to the Pacific to be “destined by Divine Providence.” Largely because he persevered, Idaho is now part of the United States.

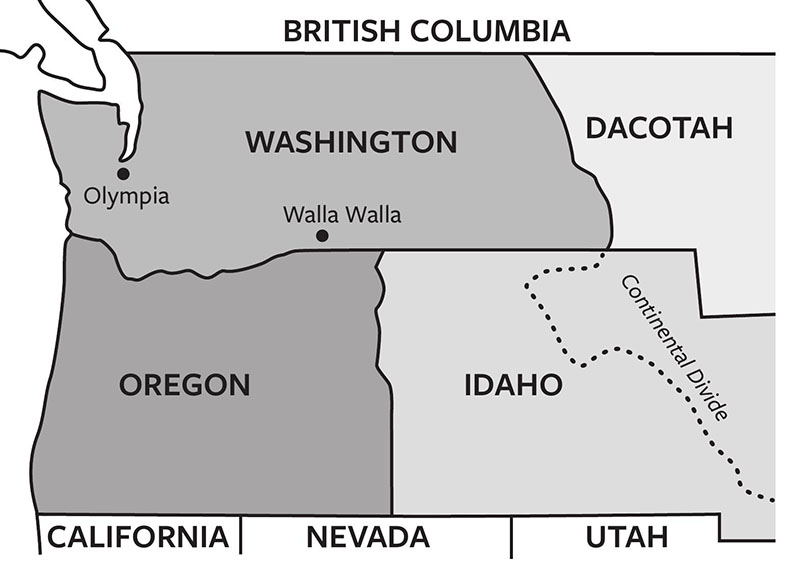

This map shows the treaty line that formed Idaho's southern border. WSU Press.

The Bitterroot Range as seen from Salmon. CJW in the PNW photo.

The Centennial Mountains are also on an Idaho border. Bob Wick, BLM.

The book's cover shows Nixon's profile in the northeast. WSU Press.

The Kootenai River runs through Bonners Ferry. Dicklyon photo.

John Mullan's regional map recognized the Northwest's east-west orientation. WSU Press.

The old Franklin City Hall. Tricia Simpson.

View of the Teton Range from Idaho. Art Brom.

Entering Idaho from Lolo Pass. Self photo.

Spain claimed vast tracks of North America, everything west of the Rockies from Mexico to Canada. Adams sought Spain’s rights to the Pacific Northwest. He proposed a straight-line boundary along the 41st parallel—today’s southern Wyoming border—to the Pacific. Spain would retain everything south of that, and grant America its rights to the north. Onís countered with a boundary farther north, on the 43rd parallel. The men haggled for months.

Monroe grew impatient: Just obtain Florida and call it a day. If Adams could not quickly get a better deal, Monroe ordered him to settle at the 43rd parallel. Adams fumed about Spain quibbling over a “couple degrees of wilderness.” Finally, Onís suggested they split the difference and draw the border at the 42nd parallel. Adams agreed. The two settled on a border possessing little logic other than giving a rest to two tired diplomats. But their arbitrary compromise had enduring significance. For the first time, the United States had legal claims to land on the Pacific Ocean. And their 42nd parallel compromise today forms the northern borders of three states and the southern borders of two others—including Idaho.

****

I figured Idaho’s other five boundaries had similarly interesting stories and wondered why historians hadn’t delved more deeply into this topic. Idahoans live in a state formed by others, people with little knowledge of western geography. For example, Idahoans might ponder why the most expensive highway project in the state has long been the never-ending effort to improve Highway 95, connecting north and south Idaho. There is no logical geographical reason for Idaho to have a panhandle. Those who drew Idaho’s borders arbitrarily gave the state that beautiful but isolated strip of land. A person cannot understand Idaho history without understanding the long, ongoing effort to unite the panhandle with the rest of the state, both economically and politically. Studying how Idaho got its shape is not just a dive into peculiar lines on a map. Those lines have repercussions.

One reason for the paucity of historical interest might be that you can’t really research the topic from materials archived in Idaho. Idahoans had no influence over the state’s contours. Researching that story would be a puzzle. But then, research is a historian’s delight. Away I went.

****

As it turned out, John Q. Adams was not done with Idaho. He got Spain to relinquish its rights to the Pacific Northwest. But Great Britain still laid claim to that land.

While Adams haggled with Luis de Onís, he left negotiations with England to his good friend, Richard Rush, United States minister to Great Britain. The Treaty of Ghent that ended the War of 1812 left many issues unresolved between England and the United States, particularly the Canadian border. Rush and Adams proposed an elegantly simple boundary solution, a border along the 49th parallel all the way from today’s Minnesota to the Pacific. Great Britain’s diplomats agreed—up to a point. That straight-line was fine as far as the Rocky Mountains. But Britain proved unwilling to give up the Northwest’s rich fur resources.

So in 1818, the countries agreed to jointly occupy land west of the Rockies—today’s British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and parts of Montana and Wyoming. Some Idahoans boast that no foreign flag has flown over Idaho. That is not true. Between 1818 and 1846, Idaho was as much British as American, and English flags flew over fur-trading posts.

John Quincy Adams—as secretary of state, president, and member of Congress following his presidency—never wavered in advocating that America control the Pacific Northwest. But it took until the 1840s to realize that dream. Increasing numbers of Americans who migrated west on the Oregon Trail—all of them as entitled to settle in what is today’s British Columbia as any resident of England—threatened England’s hold on the region. Britain finally decided to set a border. They could have saved a lot of time: essentially the old Adams concept of a 49th parallel border held sway, save for a slight dip south to give England sole possession of Vancouver Island. In 1846, the two countries signed the Treaty of Oregon, giving British Columbia to Canada, and Idaho and other northwestern states to the United States. The future Idaho just got its second border, and seventy-nine-year-old John Q. Adams had lived to see the day.

He did not live to see the creation of Idaho in 1863. Still, his relatives appreciated his efforts. His grandson, Charles Francis Adams, Jr., operated several businesses in Lewiston in the 1890s and helped plat the neighboring town of Clarkston, Washington. John Q. Adams’s great-grandsons built a Lewiston home on 450 acres overlooking the Snake River and oversaw the family’s business interests from the Adams Building on Lewiston’s Main Street. Perhaps it is time for Idaho history books to pay more attention to the sixth president and his family.

****

By 1846, seventeen years before there was an Idaho, it already had what would become its southern and northern borders, thanks to a politician who never saw the place. In the present, I started research on another state boundary.

In the records of the 1857 Oregon Constitutional Convention, I learned about Charles Meigs, delegate from The Dalles. He believed residents of Oregon east of the Cascades would never have much in common with those living west of the mountains. Meigs proposed Oregon’s eastern border should be the Cascade Mountains. In congressional records, I discovered Meigs had an ally in Senator Stephen Douglas (of the Lincoln-Douglas Debates). “Oregon should lie wholly west of the Cascades,” he declared. Over the last two years, voters in several eastern Oregon counties have proposed that the conservative eastern part of Oregon secede from the liberal western part to join a “Greater Idaho.” Had Meigs and Douglas had their way, those people already would be Idaho residents. Yet most congressmen sought states that not only were rectangular but also were of about the same width and height. A narrow Oregon held no interest for them and when it became a state in 1859, Congress mandated its current eastern border. At the same time, the future Idaho had received its third boundary, once again before there was an Idaho.

I mused that when the territory was formed in 1863, maybe

Idahoans finally got some say about one of their borders. Not so fast. In the papers of Northwest road builder John Mullan at Georgetown University, I found that Mullan had proposed an entirely different shape for Idaho. He had just completed constructing the Northwest’s first engineered highway, running from Walla Walla to Fort Benton. He knew the region well, and the chairman of the House Committee on Territories asked him to draw a map for a new territory that some were already calling Idaho. Mullan’s map showed Washington Territory extending all the way to the Rocky Mountains. Idaho would lie below Washington, their mutual border a straight line along the 46th parallel. In this scenario, today’s Grangeville would be in Idaho and neighboring Cottonwood in Washington—along with Missoula and other towns now in western Montana.

The proposal made geographical sense. Trade relations north of the 46th parallel have always been east/west, not north/south. Even today, northern Idahoans share more with Spokane than Boise. There would be no Idaho panhandle, had Mullan had his way. And he almost did. In February 1863, the House easily passed his proposal. But the Senate had different ideas. It wanted Washington to be the same width as Oregon, and passed a proposal to establish the Idaho/Washington border where it is today. On March 3, 1863, the House caved to the Senate. The next morning, President Lincoln signed legislation creating Idaho. Rectangular orderliness prevailed over Mullan’s logical vision. Congress had foisted on Idaho its fourth border, one that made little geographical sense. It would not be the last time.

To learn how Idaho got that Nixonesque eastern border, I researched a Montanan, Sidney Edgerton. Congress had created a huge Idaho. It included all of today’s Idaho and Montana and virtually all of Wyoming. By the time the first territorial legislature met in the capital at Lewiston, legislators knew the territory was too unwieldy to govern. They petitioned Congress to shrink it, and requested an eastern border at the Rocky Mountains. Then the legislators forgot about the issue, figuring Congress would do the right thing. Big mistake. President Lincoln had appointed Edgerton to the Idaho Territorial Supreme Court. As Edgerton made his way west, he got stuck in Bannack City, then an Idaho town. Snow blocked his way to Lewiston. Edgerton had political aspirations. If he could convince Congress to create a Montana territory that included Bannack City, he might profit politically. So he returned to D.C. to lobby. And he did a wonderful job—for Montana. Edgerton convinced Congress to establish the border between Montana and Idaho along the Bitterroots, far west of the Rockies. While some Idahoans labor under the illusion that only drunken surveyors could have created such an unlikely border, Edgerton—and Congress—clearly spelled out the border’s contours. Montana became a new territory in 1864. Edgerton became its first governor, Bannack the first capital. Legislators living in what is now Idaho had been completely outmaneuvered. As a result, Congress imposed on Idaho its narrow panhandle.

In 1868, Idaho received its last border when Congress created Wyoming. The boundary between Idaho from Wyoming came with little thought. The congressional records of the border “debate” take only a few pages. Senator Richard Yates of Illinois, chair of the Committee on Territories, offered the only mention of Idaho, despite the fact that Idaho would relinquish considerable territory to Wyoming. There was no need to ask Idahoans their opinion about giving up land, because “there is not a single inhabitant in that portion of Idaho transferred by this bill” (conveniently forgetting tribes). Truth be told, Idahoans could have spoken up, but no one cared. And why did Congress create that straight-line boundary? Simply “in order to attain symmetry in the geographical boundaries of the new Territory,” noted Yates. Congress had achieved its ultimate vision with Wyoming—a nearly perfect rectangle. To provide that orderliness, it took land from Idaho. That did not worry Idahoans in 1868. Idahoans of the 21st Century, visions of tourism dollars dancing in their heads, might wish their predecessors had been less cavalier. Idaho gave away the Tetons, Jackson Hole, and much of Yellowstone National Park.

****

Borders have consequences. The Kootenai Tribe understood this when the 49th parallel abruptly split their tribe in two. Suddenly, some Kootenai were Canadian, others were American, and members of the same family often lived in different countries. Residents of Franklin in southern Idaho also understood a border’s consequences. For the first twelve years of the town’s existence, they thought they had established a Utah town. When the General Land Office finally surveyed the 42nd parallel in 1872, Franklin residents discovered overnight they were actually Idahoans. Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce learned about borders after they crossed Lolo Pass into Montana. They thought they had left their Idaho troubles behind. How could they have understood the white concept of borders? They learned in that bloody summer of 1877 that a territorial border did not prevent a federal army from crossing and pursuing them.

Idaho author Vardis Fisher called his state a “geographic monstrosity.” Historian Laura Woodworth-Ney agreed: “Idaho’s odd shape [is the] result of perhaps the most counterintuitive state boundaries in the country.” As former State Historian Merle Wells noted, “The choice of boundaries did much to decide what the future state would be like.” It is humorous to think about drunken surveyors and Richard Nixon’s profile but to understand Idaho, it is critical to know how it got its peculiar shape. Those members of Congress who gave Idaho the nation’s most unusual borders did Idahoans no favors. Idaho residents have long struggled to unite their eccentrically shaped state. On the other hand, Idaho would not be Idaho without struggle.

This article is adapted from Keith Petersen’s Inventing Idaho: The Gem State’s Eccentric Shape (WSU Press, 2022). It is available through bookstores nationwide, directly from WSU Press at 800-354-7360, or online at wsupress.wsu.edu.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only

One Response to Inventing Idaho

Michael Arrowood -

at

Definitely Nixon. I was born in 1961, and as soon as I saw the Montana/Idaho border after the 1968 election (or maybe 1970, given the elementary school class I was in), it was indelibly Richard Nixon for me. I recognized it immediately, and can never unsee it. 🙂