No products in the cart.

Lewisville—Spotlight

Never Heard of It? Good.

By J. Nils Lindstrom

From 1954 to 1978, I grew up on a farm two miles west of Lewisville, a historically rich community planted on some of the most fertile soil in eastern Idaho. The early settlers knew the soil was good because the sagebrush was said to be as tall as a man on a horse. Lewisville is at the physical center of the upper Snake River Valley. On a clear day, you can see Grand Teton to the east and Mount Borah to the west, just fifty miles in either direction. When I was growing up, Lewisville was the center of my world, to which Rigby, Rexburg, and Idaho Falls were merely orbiting satellites.

Lewisville has had about 450 to 550 residents for the last hundred years. When I was young it had one gas station, a Beeline brand owned and run by Mick Rounds and his sons. It was the community watering hole; not much happened in Lewisville but the stories you heard at Rounds Service Station made up for it. As kids we waited for school bus exchanges there and listened to the old timers complain about how bad things had gotten while they chugged on their soda pops. The inflated waistlines of these faithful patrons attested to all that pop.

The Lewisville Post Office was run by Ada Lowder, who was surely the kindest, most helpful, most friendly postmistress in Idaho. She also was my Sunday School teacher in the only church in town. Ada Lowder’s Sunday stories about honesty and righteousness were indelibly engraved on our young minds.

There was one grocery store back then, the Tolman Mercantile, run by Wendell Tolman. It had a butcher shop in the back, which I heard made shoplifting in the front easy. Wendell would come to our farm and treat us to the horror of watching him shoot a steer right between the eyes. Then he’d stab it, let it bleed out for a while, and take the carcass back to his shop in Lewisville. The bloodstain in the driveway would last for months before time and weather eventually erased it. A couple of weeks after the slaughter we’d pick up heavy bushel baskets of frozen meat cuts neatly wrapped and taped in white butcher paper and labeled by hand, which filled our deep freeze.

I remember a gray wreck of a building on Main Street that looked like a horse barn but was once a movie house. My father enjoyed going there as a kid, just before talkies became popular. The piano player would read a score that came with the movie and interpret the action. It was never the same movie twice. My father used to miss the school bus on purpose on Friday nights and walk to his grandmother’s home in Lewisville proper. His parents would pick him up and see a movie before going home.

I began grade school in 1960 in the same monolithic two-story rock building my father attended. I was convinced it was built old. There were four rooms on the main floor, one of which was converted into a lunchroom. Every morning we were greeted by the smell of bread baking in the ovens. We paid fifty cents per day in advance for hot lunch. Every Monday morning, Mrs. Edith Hansen collected the money from me: two silver dollars and two quarters. Two wide cement staircases faced each other in the hall, each leading upstairs to four more classrooms. The ceilings were high and the halls echoed like a grain silo. A tube slide two stories tall attached to the south side of the building was the fire escape for the second floor and was strictly off-limits to play on during school although in summer there was no one to stop us.

The schoolmarms carried five-foot-long yardsticks to help assure strict adherence to arbitrary rules. It seemed to me they took great pleasure in smacking any kid who ran, skipped, or talked too loudly. Restrooms were an afterthought, set outside in a cement building that housed a boiler for hot water and a coal furnace, also afterthoughts. This building was loosely connected to the school by an open causeway on the west side. On cold, windy days, the restroom seemed too far to go when you had to go, and worth it to hold it. If the stomach flu hit while you were in class you rarely could get to the restroom in time, even if you bolted from your desk and ran. The sound of those occasional failures was amplified in the cement halls, heard in every classroom; even Mrs. Hansen’s bread couldn’t mask that smell.

A winning float in an old Lewisville parade. Courtesy of Joyce Lindstrom.

The Barney grandchildren with their horses, 2022. Courtesy Diana and Richard Barney.

The author with his mother, Joyce. Myra Lindstrom Merrill.

Joe Erickson and his horse Diamond. Courtesy Janeal Erickson Nield.

Sunset at Lewisville. Mary Ellen Borough.

Wells Barney, born 1901. Courtesy Diana and Richard Barney.

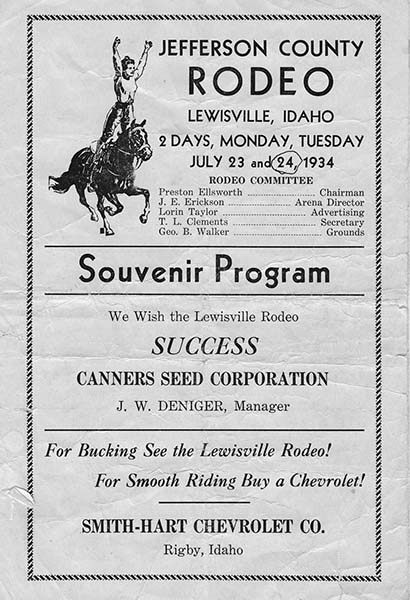

A 1934 Lewisville Rodeo program. Courtesy Joyce Lindstrom.

Except on the coldest days in winter, recess was outside—staying inside was not an option. We played in a grove of cottonwood trees to the west of the school and tried to avoid the schoolyard bullies. These trees were enormous, perfectly spaced, and aligned. They were icons of the community. In the summer, the cotton snowed so heavily that the grass turned white. In the fall, we leaped into piles of leaves so big that we disappeared on impact.

I’m pretty sure our school’s playground had the world’s most dangerous equipment. The super-tall swings produced butterflies in our stomachs and an open slide rivaled an Olympic ski jump. Many a sprained ankle was proudly earned by bailing out when the swings were too high or by losing your grip when hanging from the handles of the playground’s elevated wheel of torture. If we got hurt, we regarded it as due to our incompetence. It never occurred to us to blame the equipment. I think in a way our generation was addicted to danger.

Behind the elementary school was a full-size horse arena surrounded by a fence. At the west end a massive wooden grandstand begged for a coat of paint. It could seat several hundred people and I wondered why it was so big, because except for an occasional baseball game it never had more than twenty or thirty spectators. The truth was that the grandstands whispered stories of more glorious times in Lewisville.

Long before I was born, the arena and grandstand were home to one of the largest rodeos in Idaho. The two-day event attracted crowds of more than five thousand people to the little town. The people who organized the rodeo were no greenhorns—they were big thinkers with big ideas. Joe Erickson, a skinny bulldogger, was one of the main forces who spurred the community to host the rodeo, which included a parade, bands, and dancing in the evenings. Every year, a local girl was selected to be the rodeo queen. She would wear a long flowing gown and race a chariot pulled by two horses around the arena like a Roman goddess. My Aunt Alice Lindstrom fondly recalls how grand it felt when it was her year. “It was the only time I was ever queen of anything,” she said. The early cowboys of Lewisville were tough sons of guns on the rodeo grounds. I was sure they were the direct ancestors of the schoolyard bullies I avoided.

Lewisville is the middle-earth of Idaho’s potato country. I can remember when the potatoes were picked by hand in wire baskets and then poured into burlap sacks. They stood upright on the chocolate-colored earth, waiting to be loaded onto flatbed trucks for their journey to the potato cellars. I was six years old when a factory that provided dried and dehydrated Idaho potatoes opened in 1960. I remember sitting in a metal folding chair in the parking lot for the grand opening. It was built on the banks of the dry riverbed in front of Midway Junior High School, conveniently surrounded by potato farmers and warehouses run by Lewisville’s most prominent families: the Clements, Balls, Walkers, Hunters, and Ellsworths.

Growing potatoes was always a financial gamble. My father said, “You have to be two steps below an idiot to grow potatoes.” Well, maybe so—but there were a lot of wealthy idiots living in Lewisville and we were not one of them. We farmed sugar beets, a labor-intensive crop, especially during the beet-thinning season in the spring. But it was a more financially secure crop than potatoes, as the sugar company contracted a price with farmers at the beginning of each year. I spent the first six weeks of each spring thinning the beets with a hoe. In the summer months, we flood-irrigated them and in the fall we dug and hauled the beets in Army surplus trucks to a beet dump just north of Lewisville.

I was fourteen when I began driving ten-ton trucks filled with sugar beets. I could barely see over the dashboard. Backing up to the dump was a critical skill. The truck had to be perfectly centered and perpendicular to the bin. When I felt the back tires bump the safety bar, I would press the clutch and the brake with both feet, pull the parking brake, and shift into neutral almost simultaneously. I was small for my age but magnificent to watch behind the wheel! After I released the tailgate and engaged the hydraulic lift to raise the truck bed, the beets tumbled out the back of the truck. Potatoes bruise easily and have to be handled like eggs but beets are indestructible. After picking up my tares (the dirt and waste) in the truck I would drive to a large space behind the scales to dump them. This was right next to a row of empty barracks built for German prisoners of war during World War II.

More than a hundred boys from Lewisville served in WWII. Some later spoke freely about it and others pretended it never happened. Lewisville acquired a naval anti-aircraft gun salvaged from a battleship—no one seems to remember how this happened—and planted it proudly between the town hall and library (formerly the Lewisville Jail) on Main Street. It had two seats on a swivel base with a gun between them that pointed at the school and church across the street. After school, it was a great toy with which we could act out our aggressions. We could swivel the gun and platform with the wheel cranks that were in front of either seat and imagine blowing up Japanese and German planes. The true hellions imagined blowing up the school but nobody, not even the hellions, would have dared to blow up the church—Ada Lowder’s righteous voice lived inside every one of us.

In 1968, a new elementary school was built in Menan, our neighboring town to the north [see “Menan—Spotlight,” IDAHO magazine, November 2018]. It had low ceilings, quiet halls with bright fluorescent lights, and luxurious restrooms with easy access from almost every classroom. The old Lewisville School was to be demolished but costs for the demolition were a little too high for our town’s thrifty residents and it sat abandoned for nearly a year while they considered less expensive options. People were encouraged to salvage what they wanted, such as wiring and galvanized pipe. We kids kicked holes in the walls of our old classrooms, just because we could. The old school’s eyes were poked out by thrown rocks. It was finally determined that the best way to remove the building was to just torch it and bury the debris.

A day before the building’s cremation my father, cousin and I drove into town with a farmhand and an acetylene torch. We cut down the stainless steel fire escape slide from the school, laid it reverently on a hay wagon, and paraded it down Main Street back to our farm. Nobody had thought about salvaging that: an iconic reminder of Lewisville’s glorious days and a tribute to dangerous playgrounds everywhere.

No description of Lewisville would be honest without mentioning it’s a Mormon town. Among its settlers in 1882 were three brothers: Brigham Ellsworth and his wife Helen Gibson, John Ellsworth, and Edmund Ellsworth and his wife Elizabeth Young, the latter of whom was Brigham Young’s eldest daughter. Accompanying these five people were Richard F. Jardine and his wife Luna Caroline Ellsworth, an Ellsworth sister. Today about seventy-five percent of the town’s 450 residents are connected to the LDS faith. The town has two wards separated by railroad tracks. Everyone gets along but we don’t always see things the same way, which probably explains why the Lewisville city sign on the east end says “Lewisville 1888” and the sign on the west end says “Lewisville 1882.” Technically, they’re both correct: the first settlers came in 1882 but the city was incorporated in 1888. The sign with the year of the settlement was beautifully designed by Corrine Ellsworth, a great-great-granddaughter of Edmund Ellsworth. Some of us see the settlement date as more important.

To commemorate the town’s first hundred years, my mother, Joyce Lindstrom, wrote a comprehensive history of Lewisville that was published in 1982. She chronicled every family, every house, every great accomplishment, and a few scandals. She relishes the scandals. She’s a professional genealogist, a historian, and the author of fifteen books, many of them about genealogy and some of them historical novels. Her favorite is Jenkinsville, which recounts the scandals of Lewisville, with names changed to protect the guilty.

My mother was born in Rigby in 1931, graduated from Rigby High School, married Virgil H. Lindstrom in 1950, and the couple raised their six children in Lewisville. Even now at ninety-two years old, her memory of details is strong. For example, she volunteered this piece of information without referencing anything: “The first death in Lewisville was Harriet Cordelia Hill. She died on October 20, 1884, forcing the small community to find a proper resting place just south of town at the foot of the Lewisville knolls.”

Two years later, the land at the knolls was donated by its owner, Howard W. Rokes, and officially became the Lewisville Cemetery, where the town’s fathers and mothers, and our outlaws and war heroes alike go when they’re worn out. Row after row of pioneers, cowboys, careworn women, babies, and immigrant farmers who tore out the sagebrush and dug the ditches and canals with horses and Fresno Scrapers rest there. Residents of Lewisville gather to remember our predecessors every Memorial Day. Most years we’re able to decorate the graves with locally grown lilacs, tulips and daffodils, while former residents bring irises, peonies, and roses from warmer climes in southern Idaho or from Utah. Our family plot used to be at the far southern edge of the cemetery but in 2012 Dorothy Walker donated an adjacent parcel of land that doubled the cemetery’s size and put our formerly remote family plot at dead center.

One of the great legacies of Lewisville is the Barney family show horses. Francis Marion Barney came to town in 1915. He rented a farm from a schoolteacher named Ambray Thomas who later said, “The best thing that ever happened in Lewisville was when the Barneys moved in.” Francis Barney’s son Wells, who was born in 1901, became known for making good horses out of ornery ones. Six generations later, the Barneys still have a family dynasty they built of working with Clydesdale and shire draft horses. Teams of single, unicorn (three), four-up, six-up, and eight-up have been showcased in the Intermountain West since the 1960s. In 1973, the Barneys were invited to the Schlitz Circus parade in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where their horses pulled a calliope wagon that held a working pipe organ. The beer company even sent a recording of the organ music to play in the Barney barn so the horses would be accustomed to it before the parade. But for the most part, the Barneys prefer to show their horses regionally. They have shown them in Montana and Utah, and they never miss the Eastern Idaho State Fair in Blackfoot.

Like many young people growing up in small towns, I couldn’t wait to go to the big city and I left Lewisville at twenty-three for school in Los Angeles. I stayed there after graduation but Lewisville was always home and it pulled magnetically at me. At least twice a year, we traveled the nine hundred miles with our family of five children to the place our kids called, “The Land of No Rules.” After forty-three years of living in Southern California, I’ve returned with my wife, Loraine Parson of Rexburg, to the town where rush hour occurs every Sunday—five minutes before and five minutes after church.

When I tell my friends back in California that we moved to Lewisville, they often say, “Never heard of it,” to which I kindly reply, “Good.” Lewisville likes its anonymity. We like living halfway between the greatness of the Tetons and Mount Borah, and halfway between the large department stores to the south and BYU–Idaho to the north. It’s okay if the spellchecking software on our computers insists we live in Louisville. Even folks in Idaho confuse us with Lewiston—and, you know, we kinda like it that way.

History has had its way with Lewisville. The grandstand, the service station, and the grove of trees are all gone. The grocery store is boarded up. The church, town hall, and post office have been replaced by newer, corporate models. Much is new and improved, and we’re in the company of scores of newcomers who have moved here since the pandemic. Lewisville is a very welcoming place. Less open-minded attitudes and notions that prevailed fifty years ago have been tempered by time, wisdom, and social awareness.

You’re born into history without knowing where you are in history. By the time you’re in high school, you begin to realize things aren’t the way they used to be. Eventually, you realize that the way things used to be wasn’t the way things used to be either. That’s when you embrace history. Folks in Lewisville know where they are in history. And Loraine and I know our final resting place will be in the very middle of the Lewisville Cemetery—surrounded by history.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only

5 Responses to Lewisville—Spotlight

Laura Hayes -

at

Edith Hansen is my grandma. And boy could that lady cook.. excellent story..

Linda DeRoche Linsenmann -

at

Very good. I remember most of what you wrote about. It’s a wonderful place to raise families.

Corrine Ellsworth -

at

This will be a treasured story that is worthy of being printed and stored at the Lewisville Library, next to the Deputy’s gun. Thank you Nils for crafting a beautiful tribute.

Patsi Hinckley -

at

Great article! I am a little older than you and also remember the cafe on Main Street and Canner Seed corporation where the Perfection pea was bred. It is a great place to grow up and a great place to raise a family. We have been so blessed.

Steve Hinckley -

at

One must remember Wallace-Wally-Ball, the town clown; whom could climb a telephone pole backwards; but was scared of a mouse. I enjoyed your article.