No products in the cart.

My Other Father

The Life and Times of Austin Case

By Gary Oberbillig

It’s said that Three Island Ford just below present-day Glenns Ferry was an Oregon Trail crossing of the Snake River so treacherous it always left the fresh grave of a drowned emigrant. As a boy, I once found half an oxen shoe at the site, now known as Three Island Crossing, and shivered at the thought that I was walking on old graves. This reaction was influenced by my stepfather Austin Case, whose hometown was Glenns Ferry, and who made me aware I was growing up in a West permeated with history.

Austin, like several other important figures of my boyhood, including my grandfather J.B. Simpson and my father Ernest Oberbillig, could fascinate his listeners with a good yarn. Often the words in my stories are their voices filtered through the years and my own grown-up perceptions. He was a big man, and truth be known, I was afraid of Austin when I was small, but through the years we became better and better friends, and I’ve come to realize just how much he did for me as I was growing up.

In those times it couldn’t have been easy to accept the responsibility of raising another man’s son, for divorce was fairly uncommon then. A virtual blackout curtain dropped between first and subsequent marriages, and the only thing I knew of my Oberbillig side was a monthly child support check of $42.60 that continued to arrive until my eighteenth birthday. That amount was established by the court the year after I was born in 1938, and must have been considered ample by Depression era standards.

My mother and father had one of the shortest marriages I’ve ever heard of. They were married secretly after my father had just begun his freshman year at the University of Idaho. My beginnings were the result of a weekend tryst when my mom took the bus up to join him in Moscow from her family home in Boise.

My grandmother, Edith Kelly Oberbillig, didn’t approve of my mom and called her a “skirt,” a euphemism of the time for a girl who would not be suitable marriage material for her son. My grandparents on the Oberbillig side were newly rich in a poor western state, and my grandmother thought most girls were only after the money that was rolling in.

My grandfather, J.J., struggled for decades on hardscrabble mining claims and then struck it rich. The mining camp of Stibnite, in addition to its ongoing substantial deposits of antimony, was also the largest domestic supplier of tungsten, which was an extremely valuable asset during wartime, as it is the essential hardener for steel used in armor-piercing shells, as well as to make pierce-resistent armor.

I was born in 1937 and the U.S. didn’t enter WWII until 1941, but the approach of that event was already on the horizon. J.J. also had property at the nearby camp of Cinnebar, which was rife with ore that contained mercury. Consequently, the financial fortunes of the Oberbilligs changed almost overnight.

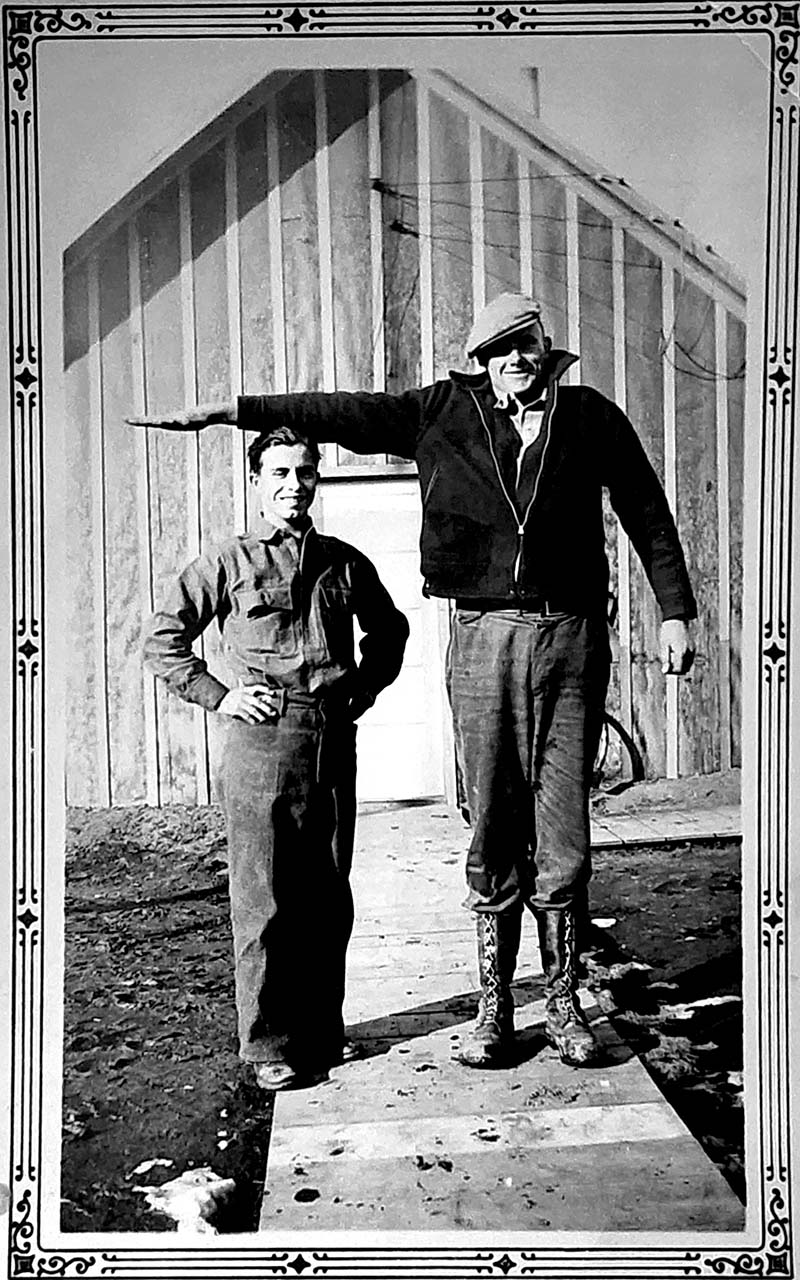

Austin towers over a coworker, 1930s.

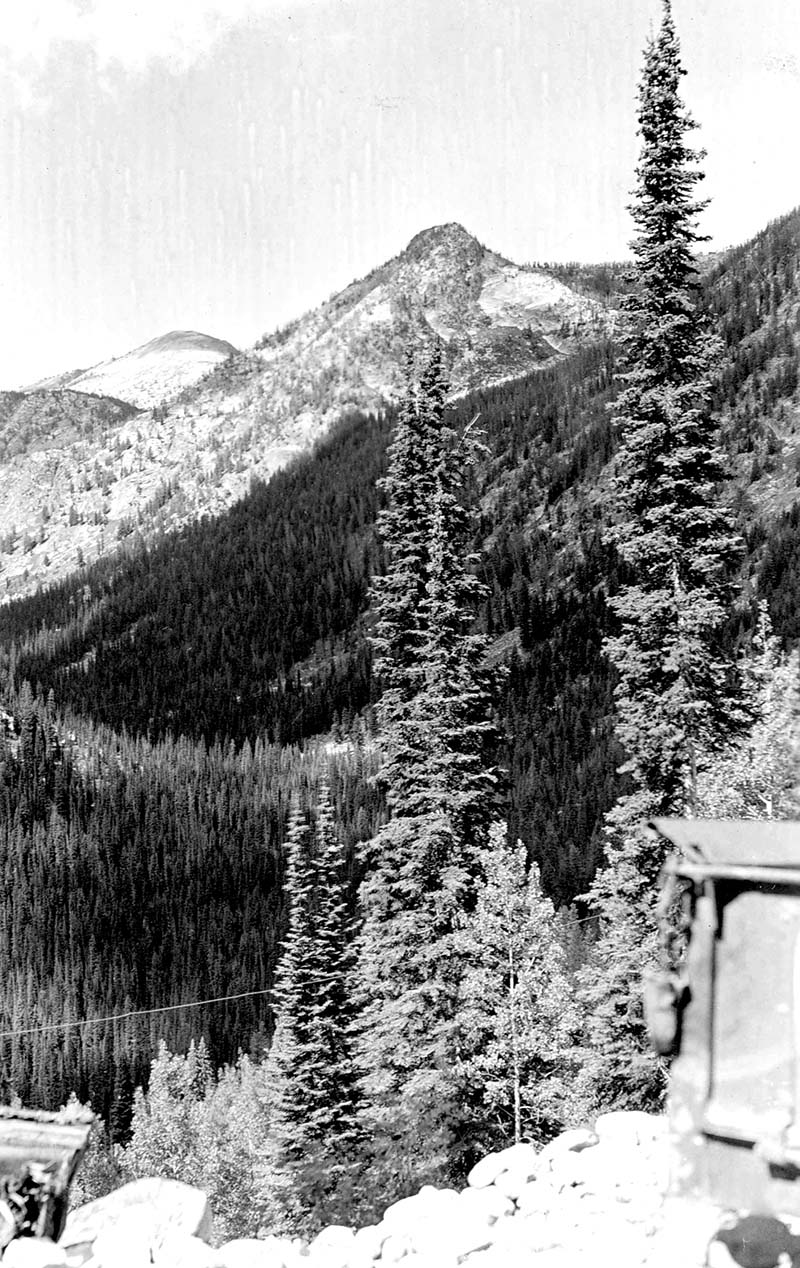

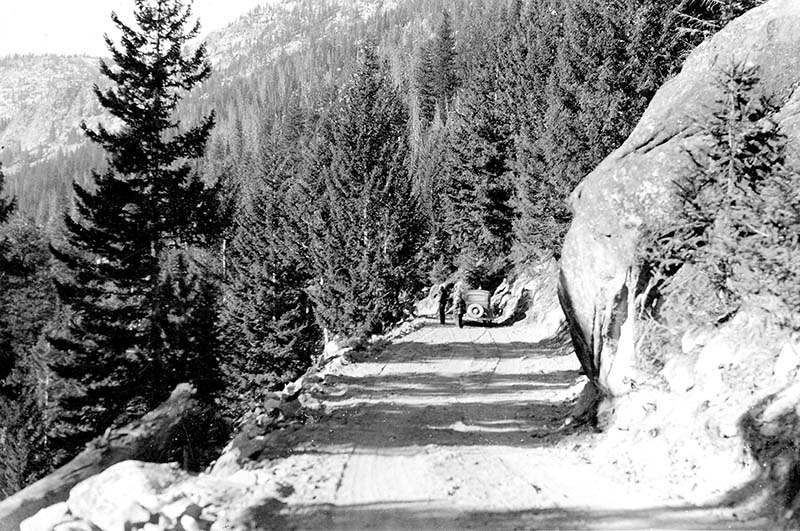

A CCC road at Buffalo Hump. ITD Collection.

The CCC-built Lowman Road and workers' camp, 1933. US Bureau Public Roads.

CCC road near Orogrande Summit, 1930s. ITD Collection.

Three Island Crossing State Park. Michel Overstreet, Google Maps.

Tractors in Fairfield. Josh Parrish.

My grandparents announced to my father that if he didn’t obtain a divorce, they wouldn’t pay for his college education. Ernie was an extremely intelligent man. For example, he had the wild talent of eidetic memory, which means he could recall an image in detail after seeing it just once. This gift usually is confined to a very few children and not to adults. Ernie was desperate to complete his education as a mining engineer and take his place in the family business. Under the threat of losing his dream, he asked my mother to get an abortion. Her answer was to slap him roundly in the chops and march off to wait out the rest of her pregnancy.

She said she didn’t see Ernie again until she went to court to try to get child support for me, as I’d arrived on schedule. The judge was in sympathy with her and ordered the payments. Both my mother and father remarried after their divorce and I used Austin’s surname until graduation from high school. Believe me, it caused some confusion among my classmates when I showed up at reunions with my birth name. Just who was this Oberbillig character, anyway?

During my last year of high school I decided I needed to meet the paternal part of myself if I was to make any sense of my heritage. I decided the easiest path was to meet my Oberbillig grandfather first of all, since I was so close to my loving maternal grandfather, John Burtt Simpson. This proved a good strategy, for grandfather J.J. Oberbillig was fond of grandkids.

I brought my high school graduation photo to that first meeting and he put it on the piano with all the other grandchildren, which was an affirmation that meant a lot to me. He also gave me three dollars to go to the circus and a stick of Blackjack chewing gum, which he kept handy for all the grandkids.

I met my father, Ernie, after he inquired about the photo on his father’s piano. Shortly after that, I met his wife Carol and my two sisters, Diana and Janelle. I say “sisters” because right from the start we never went by halves in our relationship, for which I’m grateful. I’d had experience on a survey crew and got to know Ernie through working with him as a chain man on mine claim surveying jobs. Later I worked for the Oberbillig family in the mining operations in Yellow Pine, the summer before Molly and I married in 1961.

Austin was born in Arkansas, I think around 1906, but he grew up in Glenns Ferry on the green Snake, which often winds through my dreams these days. As a boy, he delivered groceries to an elderly Kittie Wilkins, the famed Idaho horsewoman who sold Idaho horses virtually around the world [see “Queen of Horses”, IDAHO magazine, Part 1, October 2008 and Part 2, December 2008]. In part because of his satisfaction with this job, he turned down an offer after WWI to accompany his maiden aunt, Miss Simmons, a French language teacher, on a visit to France.

Even years later, his ambivalence over that decision was evident to me. While his aunt was in France, she adopted an orphaned lad, but he and Austin never became the best of friends, perhaps because Austin insisted on mispronuncing the boy’s given name, Robert. Instead of the proper French pronunciation of “Robe-air,” he used a burlesqued, “Raw-bear.”

Austin loved animals (except untrustworthy horses) and dogs would follow him around, tails wagging frantically, hoping for words of approbation. It was the crooning tone he used and not the words themselves that appealed to the dogs, for he would assure each and every one that they were “a nuisance, an abomination, and a detriment to mankind.” And then he would give each one a good scratch at the root of the tail, which dogs seem to crave, and a pat on the head, to send them and their gyrating tails on their way.

He had a pet deer that he’d found as a fawn beside a doe killed by a cougar. He brought the fawn back to camp, and named it Oscar. After Oscar grew into a big-antlered buck, Austin gave him to the zoo in Julia Davis Park in Boise, for he knew a tame deer wouldn’t survive even one hunting season. Every month or so, we’d go to the zoo to visit Oscar and Austin would feed him a single cigarette, on the theory that nicotine got rid of worms and other internal parasites.

Maybe it did, for Oscar lived to be a very old deer, his antlers full of random spikes.

In a photo I have from the 1930s, Austin stands grinning with an arm outstretched from his six-foot-six-inch frame like a cantilevered crane. A good tall drink of water, as they say. My mom always claimed she could trace the entire map of Ireland on his face, and the imperishable grin in this photo seems to confirm it.

Despite being so big, Austin was always taken with things in miniature. I recall a palm-sized ball-peen hammer he made on a lathe, and also miniature wrenches and other mechanic’s tools. I suspect his occupation as a master mechanic was never far from his thoughts, and he took great pride in a job well done. After he went into business for himself, he always worked solo, driving his old panel truck to the farmyard location of anything that needed fixing. He claimed he could never hire anyone to help him, “because there’s no way I can absolutely guarantee another man’s work.”

The shorter gent under Austin’s arm in that 1930s photo had an impressive story of his own. An Italian from the East Coast, he was connected with the mob, Austin said, and had narrowly escaped when his dad and uncle were shot dead on either side of him. Whenever Austin told this yarn, his thrilled listeners always experienced a shiver.

The photo exemplifies the good-natured horseplay and hijinks Austin described during the gloomy days of the Great Depression in the 1930s, when he worked for the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). It was a gambit of President Franklin Roosevelt and his advisors to ease the economic hardships of that era by providing jobs for the many unemployed who combed the country looking for work. The CCC drew men from everywhere, including Austin and the other man in the photo. Eleanor Roosevelt, an unusually influential First Lady, encouraged a parallel program for financially hard-pressed women called, with euphonious humor, “She She She.”

The benefits of the programs went several ways. Workers had plenty of good grub to eat, medical attention if needed, and a dry place to sleep, even if it was just a big canvas tent. The men had a wage of thirty dollars per month, twenty-five dollars of which was sent back to families at home. The remaining five dollars were enough to buy small items like shaving gear. It wasn’t a lot of money by present-day standards but was maybe sufficient for the bleak 1930s.

Among the famous figures who worked in the CCC camps during the hard times were actors Raymond Burr, Walter Matthau, and Robert Mitchum. Others who became prominent in American life included baseball player Stan Musial and test pilot and Army Brigadier General Chuck Yeager, the first man to break the sound barrier in level flight. The CCC boys dozed out new roads, built dams, fought forest fires, built National Park buildings and numerous other structures. Throughout Idaho and the country, the environment benefited from the blisters on their hands. They are even sometimes associated with the beginnings of today’s environmental movement.

Certainly, hard work, self-respect, and the “can do” spirit it engendered had a lasting effect on these men. The Great Depression marked people, just as the Civil War had marked an earlier generation. It affected their thinking in small ways down through succeeding decades. For example, my friend Mark could never throw a bent nail away.

My mother said she despaired as a young girl of ever having a dress that was not a hand-me-down. My uncle took to marking the cards in a deck in pursuit of the elusive dollar. A blues song of the time goes: “If I ever get my hand on a dollar again, I’m gonna hold onto it ‘til the eagle grins.” It continues with the quietly despairing: “Nobody knows you when you’re down and out … In your pocket not one penny. And your friends, you haven’t any.”

As a diesel mechanice for the CCC, Austin repaired heavy equipment such as the Caterpillar tractors used for the heavy work of road-building. This probably helped him to get a job with Bunting Tractor Company when the Depression subsided. He repaired tractors in the fields to keep WWII crop quotas flowing out of Idaho. During the war, the same determined spirit that had taken hold in the CCC years could be felt on the blood-soaked beaches of Normandy in the struggle to roll back the dark tide that had engulfed Europe. Like most, Austin volunteered for the wartime draft, but he was near the age limit and apparently the local draft board deemed him to be more valuable where he was. By then, two of his brothers already were overseas in the Navy.

In the bountiful grain-producing town of Fairfield, he worked alongside a man named Jimmy Yamamoto, who had come to the Camas Prairie years earlier from Japan. After Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor, Jimmy was in danger of being interned with his family, but they were protected by many of the local people who interceded on his behalf [see “You’re Not Taking Him,” IDAHO magazine, June 2012]. They knew Jimmy to be a trustworthy, reliable citizen, and moreover, he was an essential diesel mechanic, relied on to help keep the big Cats rolling.

As for my stepfather’s legacy, perhaps the most lasting thing was an invention. Farmers on both sides of the Snake River near Fruitland may still recall that Austin Case and a Japanese-American partner came up with the first commercially available gadget for distilling mint oil. It became a profitable crop in the Treasure Valley region along the river.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only