No products in the cart.

Not a Pig State

But the Sows Still Sing

Story and Photos by Diana Hooley

Idaho is not really a pig state. That distinction probably goes to our misnomer, Iowa, but I’ve always liked pigs. Growing up in the ’60s, I thought Arnold, the pet pig on the TV show Green Acres, was enormously charming. Later, as a gangly teenager, I visited my aunt’s farm and was tasked with slopping the hog. When the old boar angrily bucked against the panels of his pen, I suddenly realized not all pigs were as sweet as little Arnold. Still, I was fascinated. When I was newly married, we moved to a small farm near Hammett. One of our first livestock purchases after the requisite goats (back then new couples living outside of town had goats, don’t ask me why,) was pigs.

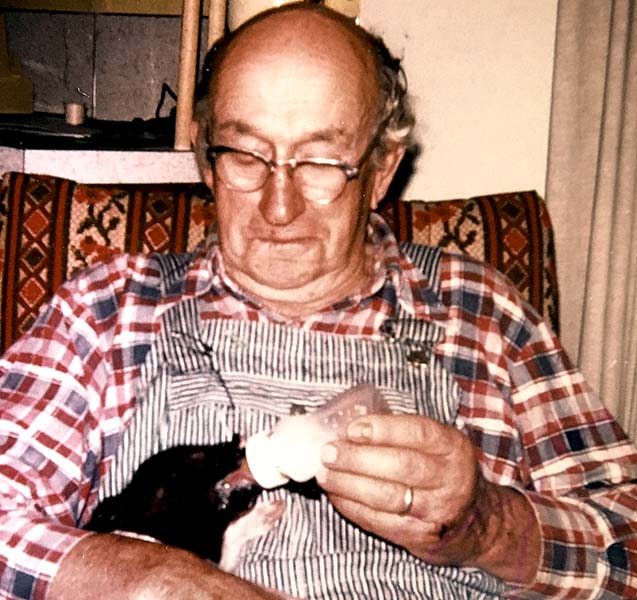

Uncle Willard, whose house was just down the gravel road from us, raised pigs, and encouraged us to purchase a couple of sows ourselves.

“Mother (Uncle Willard’s wife) and I—well, we talked about it some. She said let’s quit farming and start raising flowers. And I said let’s quit farming and start raising pigs. So we did both!” Uncle Willard chuckled as he leaned on the shovel he was using to open a plugged water ditch near their flower bed. “Best decision we ever made.”

My husband Dale built a nice shelter under a grove of Russian olive trees for the two young gilts (female pigs) we purchased at the Nampa Livestock sale barn. Sam, our neighbor, loaned us his boar and after whirlwind courtships and pregnancies, all of three months or so later, I found myself a midwife attending the birth of two litters from our sows. I clung to the rail of the pig pen that cold March in an old jacket and mud boots as I listened to the sows groan in labor. Uncle Willard was kind enough to drive down in his pickup and see how the birthing was going.

“Listen,” he said. “Hear her singing?” Uncle Willard leaned over the pig pen fence, his face keen and turned, like he was listening for the wind. Singing? Pigs? He smiled, “When they have their babies, the mothers sing to them.”

Looking for lunch.

At the trough.

Getting a snoutful.

The author’s Uncle Willard with a piglet.

We didn’t have any farrowing crates to hold the sows steady as they dropped their babies. New sows have been known to step on piglets or kill them in other ways. The plan was to grab the piglets as soon as they were born and move them to one of their mother’s teats. Everybody, sow and offspring, needed to calm down and get acquainted with one another. I worried though, about climbing into that pen with two agitated, four-hundred-pound pigs.

Uncle Willard pointed with an arm knotted like the branch of a burl oak. “Sure, sure. Go ahead and get in there with the girls when it’s time. They’ll be hurting so much they won’t take any notice of you.”

And so I did. I kneeled in the muck behind a sow and watched my first live animal birth. It was smelly and gross and absolutely fascinating. The piglets were so tiny, so precious. I loved watching them nurse and barely restrained myself from patting the rear of the sow to congratulate her. The less she knew about my presence, the better.

It was early spring and cold, especially at night, so we scattered dry, fresh straw along the ground of the pen and mounted a heat lamp in a slatted roof at its corner. All went well at the nursery for the first few days, until the middle of one night when we heard our dog, Misty, barking wildly. My husband peeked out the bedroom window of our trailer house and hollered at me to get up. “The pig pen is on fire!”

Later, we figured out the fire must have started when one of the sows, in an attempt to build a nest, used her snout to pile straw up in the corner close to the heat lamp. We frantically fought the fire, shoveling dirt and squirting water from our garden hose, but tragically, both sows and several of their newborn were either burned to death or had to be put down. Uncle Willard came and helped us shoot the two sows. Dirty and exhausted as the morning light broke, we took comfort in the fact that we were at least able to save twelve of the twenty-four newborn piglets.

Standing in my smoky bathrobe, I surveyed the carnage and asked Dale, “What do we do now?”

“We put the piglets in the shed. Then we’re going to have to bottle-feed them.” He sounded determined.

Once, when a mother cat had been killed by an owl, I’d tried to save her batch of kittens—all to naught. It was so disheartening watching those kittens gradually die, one by one. I thought then that humans were poor replacements for animal mothers. I mentioned my misgivings to my husband but he just quietly said, “No. Pigs are thriftier. You’ll see.”

The first week feeding the surviving piglets was the roughest. We bottle-fed them every three to four hours, even throughout the night. I mixed up a batch of formula with water in a bucket, and then used a funnel to pour it into the long neck of a glass bottle. Next a pink rubber nipple was placed on top of the bottle. At first the piglets squirmed in my arms, but once the nipple was in their mouths, they sucked greedily. Not surprisingly, they ate, well, like pigs.

Uncle Willard strolled into the shed a few times and watched us feeding the piglets. “Looks like things are going to work out just fine,” he smiled. “We all go through rough patches.”

I found myself becoming attached to our little drift of piglets. One piglet in particular won my heart. She was one of the smaller ones, apparently a runt. We didn’t think she’d make it in the long run because she’d sustained some damage to her back leg from the fire. When I came into the shed with the bottle to feed the piglets, she was always last to limp over. Of course, I wanted to feed her first. After all, she needed the nourishment to heal. My husband warned me not to become too attached. We decided to name this little piggy “Legs,” because of her injury.

Amazingly, all our fire piglets thrived and within a few months were shipped off. All except Legs. She found a home on the neighbor’s farm where she went on to live long, lazy days producing many happy litters herself. And Uncle Willard? Just a little over a year later, on Father’s Day, we stood in a country church singing an old hymn when Uncle Willard suddenly collapsed back onto the pew seat, and died of a heart attack. It was the way he’d want to go, in church and on his special day, for he was more than an uncle, at least to us. He’d been like a father, supporting and teaching us how to raise pigs on our little Idaho farm.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only