No products in the cart.

On Slick Rock

Reenacting the First Ascent of ’67

Story and Photos by Mark Weber

Twelve miles east of McCall, hidden in the folds of the Salmon River Mountains, lies one of Idaho’s most coveted long-climbing objectives—the thousand-foot-tall sweep of solid granite known as Slick Rock.

Here on a sunny summer day in 1967 three local climbers, Harry Bowron, Jim Cockey, and a man named Dorian (whose surname the others could not recall), set out to scale the imposing east face of this monolith. In a landscape where mountain peaks scrape the sky, deep valleys rend forested slopes and crystal clear streams tumble over boulders, this colossal swath of granite rises almost a fifth-mile and stretches nearly a half-mile in breadth.

In the nearly half-century that has passed since this first ascent of Slick Rock, the adventure and climbing experience remain much the same. On a morning in July 2011, the sun is shining brilliantly overhead as we hike the hillside that leads up to the wall. The rushing stream in the valley below echoes off the surrounding slopes, while the trail splits a thick carpet of wildflowers and verdant shrubbery. Two of our party of four have been here before, while the others are making their first pilgrimage to a “big” climb.

A gentle breeze sweeps through the towering pine forest, rustling branches, and I sense a few butterflies also rustling in stomachs. From this vantage, the sea of granite that looms above is intimidating if you have never been on a big route before.

The upper two-thirds of the wall are punctuated by three staggered, ascending cracks that split the pavement of solid stone for more than six hundred feet. These “triple cracks” seemed to provide a logical path to the summit for the first ascent party. In the late Sixties, the only reasonable possibility for protecting a climbing team on Slick Rock’s blank and seemingly featureless terrain was pitons hammered directly into these fissures.

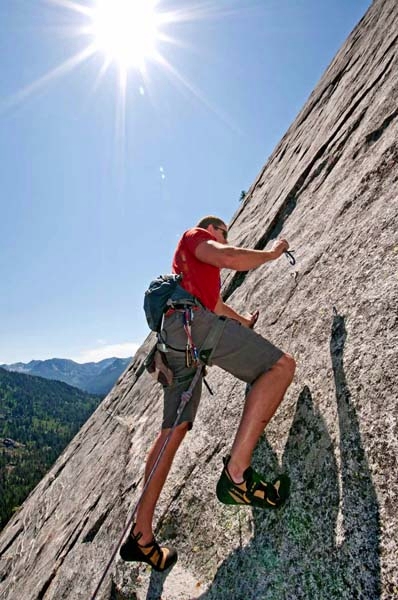

Elijah Weber on Slick Rock's Regular Route.

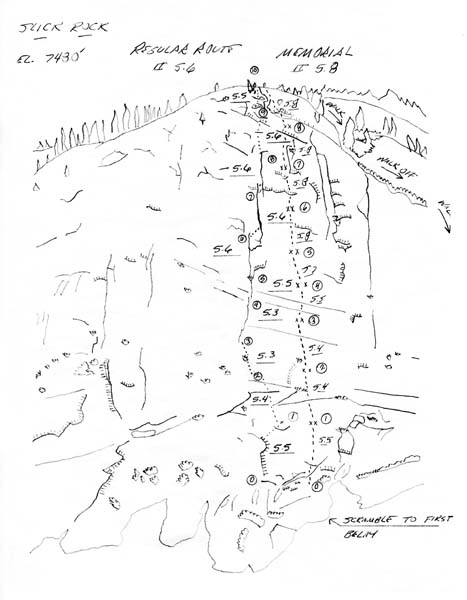

The author's topographical map showing the routes and degrees of difficulty in ascending Slick Rock.

This face shows how Slick Rock got its name.

Jamie Brown climbing the Regular Route, which is rated 5,6.

Elijah gets a handhold in a crack on the rock.

Elijah Weber and Nikki Tate rack gear before climbing the Memorial route.

Rock climbing equipment is much improved since Slick Rock was first surmounted in 1967.

Rock climbing equipment from 1967 including pitons, piton hammer, and carabiners.

Elijah Weber rock climbing Memorial, which is rated 5,8.

Armed with a ninety-foot length of twisted nylon rope called Goldline, a handful of iron pitons, a small collection of aluminum carabiners and a tangle of looped nylon slings, the team launched off on what would later become one of the most popular big rock climbs in the state. With all three climbers tied into the same rope, the trio made surprisingly rapid progress up the bottom two-thirds of the wall.

Meanwhile, Jim’s parents and his two younger siblings had traveled in the family sedan from McCall to watch the party scale the monolith and view the adventure as it unfolded. After about seven hundred feet of moderate climbing, at a point near the end of the uppermost of the three cracks, the climbers encountered a steep and blank headwall. Pausing on a shelf they would later call “Lunch Ledge,” the party rested, scanned the formidable terrain looming above, and weighed their options. From her position below the soaring wall Jim’s mother could sense the party’s indecisiveness as they paced back and forth across the ledge for nearly an hour. She soon realized that they were in a serious spot of trouble.

Jim’s younger brother, Art, remembers his mother becoming increasingly unnerved and commenting repeatedly, “Those damn kids have got themselves rat-trapped!” After much deliberation, Harry finally traversed left, in search of a reasonable passage to the summit. Twenty feet of tiptoeing across a small quartz dike, followed by tenuous and insecure friction-climbing, in which he generated traction by smearing his hands and feet on the rock’s smooth surface, led him to a small under-cling crack.

This crack would accept the team’s pitons and afford much-needed protection and safety. The remaining climb covered two hundred feet of delicate friction and strenuous lie-backing, in which he progressed up the face by pulling outward with his arms against a crack or other hold while pushing his feet in the opposite direction, to create friction. As the sun began to drift toward the horizon, the last bits of granite passed under the trio’s boots and they emerged onto the airy summit.

As I stand at the base of the wall, the climbing route towering overhead, I can’t help but imagine what it would have been like here in 1967. We lace up climbing shoes that boast sticky rubber soles but Harry, Jim, and Dorian would have been shod in clunky, lug-soled hiking boots. Our harnesses are safe and comfortable, while their waists were lashed with webbing that provided a place to tie the climbing rope. Our gear includes the latest high-tech climbing gadgets, which seem engineered for aerospace use rather than for mountaineering. The original adventurers carried only several pounds of clanging pitons, carabiners, and a heavy hammer.

There is no shortage of stellar climbing opportunities in Idaho. The Sawtooth Mountains in central Idaho offer long routes, as well as some of the best wilderness climbing in the western United States. Up in Idaho’s panhandle, the golden granite of Chimney Rock rises fortress-like, hundreds of feet above the Selkirk Crest. In the southern reaches of the state, myriad granite spires adorn the world-famous City of Rocks National Reserve. What distinguishes Slick Rock from Idaho’s other climbing possibilities is its exceptional length and moderate difficulty. The Regular Route is rated Grade 2, 5.6 on a scale that currently goes from 5.0 to 5.15 and is eight to ten pitches (rope lengths) in length.

Nowhere else in the state can climbers ascend a thousand-foot wall at such a moderate grade. This combination makes Slick Rock the perfect destination for climbers who are interested in challenging themselves on bigger objectives, as well as more experienced climbers who are looking for an enjoyable outing in the mountains.

Once we are on the rock, the climbing unfolds in a puzzle of foot and hand holds. The higher we climb, the better the views. The forest soon fades into the valleys below while mountain peaks rise all around us. As we move higher the climb becomes steeper and more engaging. But I sense growing apprehension from the apprentices in our party. Looking down nearly seven hundred feet from Lunch Ledge to the tiny trees and miniature cars on the road will do that. It’s easy to see why this terrain stymied the first ascenionists fifty years ago. The hand and foot holds that were so abundant and obvious lower on the wall have all but disappeared, replaced by a few insecure and slippery moves leading to the crack system above.

With courage afforded by our sticky-soled climbing shoes, those desperate moves of long ago seem a bit tamer today. After two more rope lengths of enjoyable climbing, we crest the final bulge of smooth stone to the summit. On top, the views are nothing short of inspiring, and we all ride the emotional wave that comes from the effort and excitement of an adventure such as this.

While there are several routes that now ascend the east face of Slick Rock, two offer the best climbing and see the most ascents. The original line of the Regular Route offers climbers a “traditional” experience. Traditional refers to the fact that climbers ascending this line must use natural features to secure protection in case of a fall. This is accomplished by utilizing removable gear, things like spring-loaded camming devices and “nuts” placed in cracks or by “slinging” the occasional tree or rock “horn” with a length of looped and knotted webbing called a runner.

In contrast to the “trad” climbing on the Regular Route there is also Sport climbing on a more recent route named Memorial (Grade 2, 5.8). This immensely popular route ascends the wall just right of the Regular Route. For protection, climbers on Memorial use bolts that were drilled into the rock face by the first ascent party.

After an adventurous and fun day climbing Slick Rock, climbers can cool off with a swim in the cool, crystal-clear water of Payette Lake, and then head into town for a celebratory dinner and drinks. For me, it’s the archetypical McCall experience if ever there was one.

How to Do Slick Rock

ACCESS: From the center of McCall, take Davis Avenue toward Ponderosa State Park, and turn right onto Lick Creek Road. Continue past Lake Fork Campground and up the canyon until Slick Rock comes into view on your left. Park in the pullout at the signpost. Cross the creek on a logjam directly below the pullout and climb the hillside to the base of Slick Rock.

THE ROUTES: Both climbs start almost directly below the summit. For the Regular Route, scramble to a rock feature that resembles a small, left-facing, open book. From near the end of this book, traverse right and continue upward onto friction to the belay in a sloping dish at a bolt. From there, just shoot for the triple cracks above. The Memorial Route begins on the slabs several yards to the right of the Regular Route.

DESCENT: Walk off in the gully to the north of the summit.

The author extends special thanks to Art Troutner, Jim Cockey, Harry Bowron, and Ray Brooks for their historical recollections and anecdotes, without which this story could not have been told.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only

One Response to On Slick Rock

Bill Weiss -

at

My dad worked at the Lake Fork CCC camp. We lived on north side of the road in a clearing that had a big rock in the middle (it had really shrunk when I went back there). We lived in two 12×14 tents connected. I remember seeing Slick Rock every time we went and came back from McCall. It was impressive then and still is.