No products in the cart.

Scammed

A Bad Boom in Idaho

Back when it seemed email had just been invented, a plea arrived in my in-box for a substantial sum to help a stranger in dire straits in a distant country, with the promise that I’d be paid back. The note was so transparently a grift, and so badly written, that I laughed aloud. But the grifters have gotten cannier since then, and I’ve been suckered more than once.

This is important to admit, I learned during a recent Boise briefing on scams. The stigma of being taken by a con is a big reason why very few such crimes are reported, as was stressed by a formidable assembly of experts from federal, state, and non-governmental groups under the auspices of the Federal Trade Commission and the national nonprofit Ethnic Media Services.

“Listen with empathy” to the stories of victims, said the meeting’s moderator, Sandy Close, because we all get scammed. Sandy, the executive director of Ethnic Media Services, further advised us not to blame the victim, but the scammer.

Idaho US district attorney Joshua Hurwit told attendees his office creates spam and phishing emails that it sends internally, to keep its people on their toes. “I’ve fallen for these emails,” Josh conceded, demonstrating that I was in good company.

Several groups appear to be prime targets, old folks among them. “These are emotional crimes,” noted AARP Idaho’s community outreach director, Cathy McDougall. “They’ll find that vulnerability.” For example, she said, seniors might be grieving from a recent loss, or suffering from cognitive or physical decline and afraid to lose their independence. They can be hesitant to admit someone might be manipulating them, and the scammers reinforce this reluctance by preaching silence.

“The self-assault they put upon you is very powerful,” she said. “They go into your mind and steal your power to believe in your own reality.”

Immigrants also are at high risk. Newly settled people from Afghanistan, the Congo, and Ukraine told attendees of being harassed by scammers. For example, Afghani immigrant Homeyra Shams described how a caller to the bakery and café she started in Boise told her the electricity would be shut off unless she paid $450. She knew the bill had been paid, but her father had just died, the café was hurting financially from the pandemic at the time, and she was not in a strong frame of mind. She almost paid, in cash, but then asked for advice and refused the scammer when he called again. Homeyra got a round of applause from us for that.

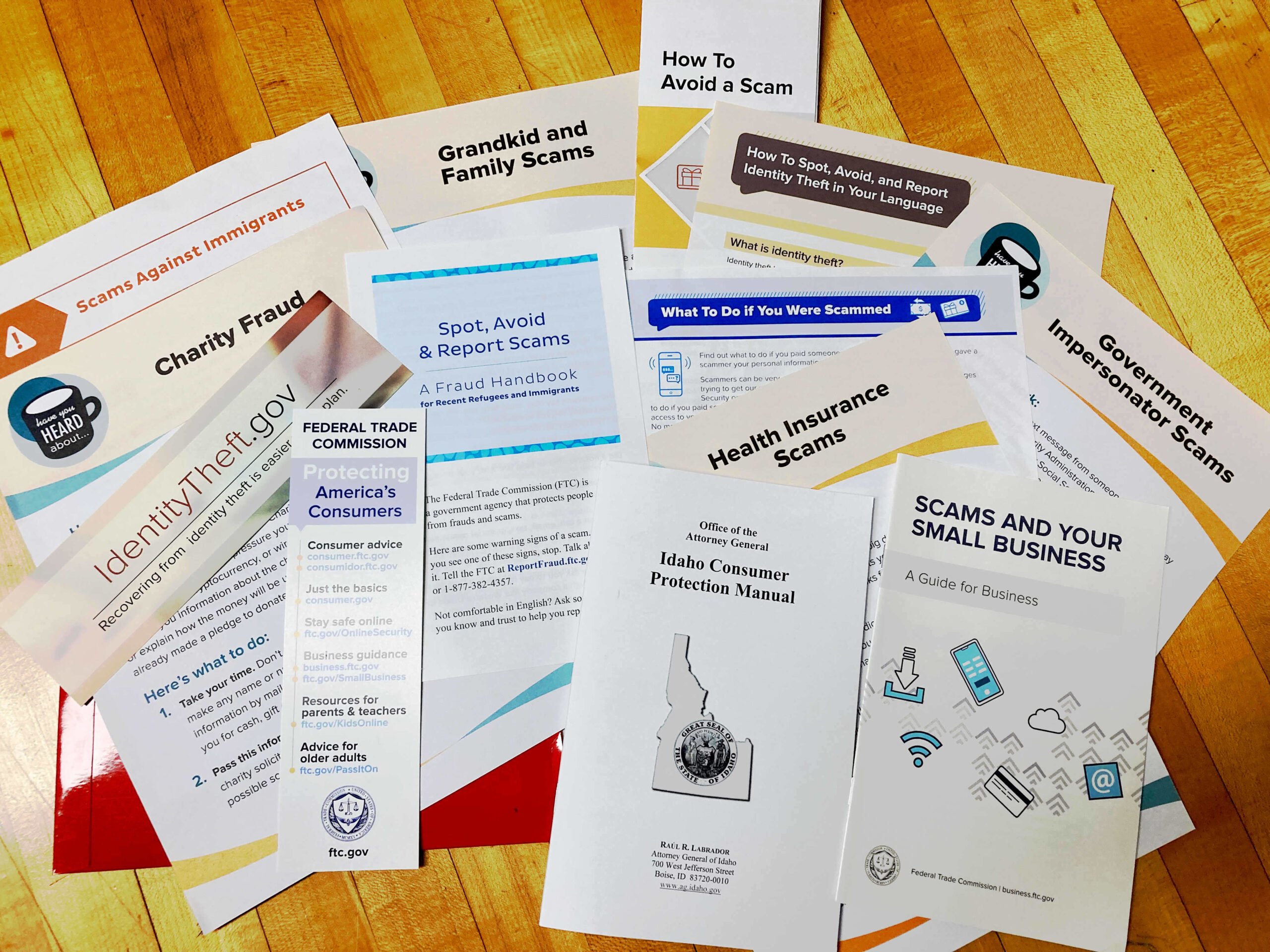

There's no shortage of literature on scams from various agency. Steve Bunk photo.

Sean Mazarol, an assistant US district attorney in Idaho, talked about migrant farm workers whose foreman made them pay a “recruitment fee” of from $250 to $2,500 each year, supposedly to renew their temporary visas. This scam went on a long time, Sean said, before a worker finally reported it to the farm’s upper management, who went to the police.

“There is a lack of trust in authority within our Latino community because of things that have happened in the past,” said Mari Ramos, chief executive director of the Idaho Hispanic Foundation. People fear retribution if they complain and they worry about losing work, she said, plus they might not be sure anything good will come of it. Also, job arrangements and other requirements are different in their home countries than in the US, and this newness can be confusing.

Mari gave an example of a recent case involving an undocumented worker cohabiting with a woman who took all but twenty dollars per week from his pay.

Joshua, the district attorney, said being forced to stay in one place like that could be a trafficking crime, depending on all the circumstances. Sunrise Ayer, who is deputy director of Idaho Legal Aid Services, said victims of domestic abuse, sexual abuse, or trafficking can come to her office.

Where to go to report scams was a big question. FTC investigator Eric Setala suggested that because different agencies deal with different types of scams, it’s important to report everywhere. At first, it didn’t sound like anyone in Boise had a comprehensive list of helpful groups, but then Boise police officer Brad Thorne spoke up. Brad is a financial crimes detective described to me by Sean Mazarol as the guy who knows more about scams in Idaho than anybody else. Brad told the group he has a template of organizations involved in controlling scams. He also has a Facebook page about all this.

Celia Kinney told people to check out the Idaho Scam Jam Alliance of fraud-busting agencies that she runs through the consumer affairs office of the state’s department of finance. They hold events and webinars. I liked her description of Fraud Bingo at senior centers, games that are full of little explainers.

Brad Thorne estimated only ten percent of Idaho scams are reported. He said of the scammers, “It doesn’t matter where they’re at, we will go after them. It could be a different country.”

He has a special interest in crypto currency scams. There are eighty crypto kiosks in Idaho, he said, where people can go to buy crypto with US dollars using a cash app. Unfortunately, the alternate currency is sometimes worthless.

Crypto isn’t all that big in Idaho but it has a big impact in dollar terms, said Cameron Naskashima of the Better Business Bureau, which offers a Scam Tracker on its website. In Idaho from January to mid-April of 2024, reported losses from scams totaled $207,000, of which crypto scams accounted for $190,000. In terms of the most common scams, online purchases, phishing, and fake job opportunities were the leaders. The employment scams were mostly about going after people’s bank accounts or getting them to buy equipment, he said.

For the last full year, 2023, Idahoans lost about $40 million to fraud, said Jennifer Tourje, assistant director of the FTC’s Northwest Regional Office. There were 715 reported cases of fake online purchases and 1,500 imposter scams, such as when a fake bank or Medicare representative wants your details or someone supposedly in distress needs money. Jennifer said there also were more than 1,100 identification thefts last year in Idaho.

The two groups most vulnerable to ID theft are older people and children, said Sunrise Ayers, the Idaho Legal Aid official. The seniors not only are reluctant to report a scam because of the perceived stigma but they also are likely to have assets that make them attractive marks. Sunrise said the ID theft of a child might not be discovered for years, until the child comes of age and tries to become financially independent. Foster kids are at highest risk.

There are two main scenarios under which theft of a child’s ID happens, she explained. The first is a data breach. The second is when family members open accounts under the names of the children, for example, to avoid utility bills, sometimes not realizing the future financial implications of this dodge. In other cases, the parents are domestic abusers.

Sunrise suggested that especially for children, adults can help to prevent such fraud by asking a credit agency to do a manual search of the minor’s social security number, which doesn’t open a credit account. Try to avoid putting a child’s social security number out in the world, she warned. Red flags include seeing credit card offers or bills in a child’s name.

Scam victims who already are traumatized, especially by sexual or domestic violence, may feel guilty, fearful, or personally diminished, said Cynthana Clark of the Elmore County Domestic Violence Council. Reporting to a male officer can make it harder for females. Jennifer Tourje’s advice was to empower such women by saying they’re taking charge and helping to ensure this won’t happen to others. Joshua Hurwit pointed out that various groups have victim/witness specialists who can make the reporting process easier for people.

There also are tax scams and all sorts of postal scams going on in Idaho but the state’s biggest current problem is construction and contractor fraud, said Stephanie Guyon, deputy attorney general in the consumer protection division of the Idaho Attorney General’s Office. For many years motor vehicle scams were the worst plague but since the building boom that began during 2022-23 in the Treasure Valley and in the state’s north, people who don’t know how to run a construction business have been the main bugbear.

A swimming pool contractor who took deposits and then didn’t do the promised work operated somewhat like a Ponzi scheme, she said, because the company used such fees to finance other jobs. For example, the contractor promised to build a swimming pool in one month for $110,000 up front but then spent the money elsewhere.

“It doesn’t matter to our office if you intended to scam someone or you are simply a bad businessperson,” Stephanie declared.

Moderator Sandy asked how all this malfeasance could be boiled down to headlines, and panel members complied with one-liners:

Reporting matters.

Listen to and believe victims.

Justice is achievable.

Go slow.

—Steve Bunk