No products in the cart.

Small Town, Big Building

What a Boon

Story by and Photos Courtesy of John Beckwith

I read a news article last year that proclaimed the old YMCA building in Kellogg was in such poor condition it could not be salvaged. A photo showed the cracked roof beams. This brought back memories of the building flourishing with activities, the strong support from the community, the special features of the mining area, and the beauty of northern Idaho. I realized the structure was very old, just as I am.

When I first stepped into that building in 1961 to take my initial job after graduation from the University of Idaho, it already was more than a half-century old. I had been hired as physical director, which meant I would oversee all physical activities and the city recreation program. I had been deeply involved in such activities at the Boise YMCA, which included directing the day camp and, later, the summer camp on Payette Lake in Valley County. In Kellogg, I remained the YMCA’s physical director for five years and then spent another five years as executive secretary, in charge of all operations.

When I first walked into the building, I was assailed by the familiar odors of any YMCA: chlorine from the pool, the musty gym from fifty years of use, the echo of kids’ voices, but there was one surprising smell. Cigar smoke hung in the boxing room. I knew then I was in the right place.

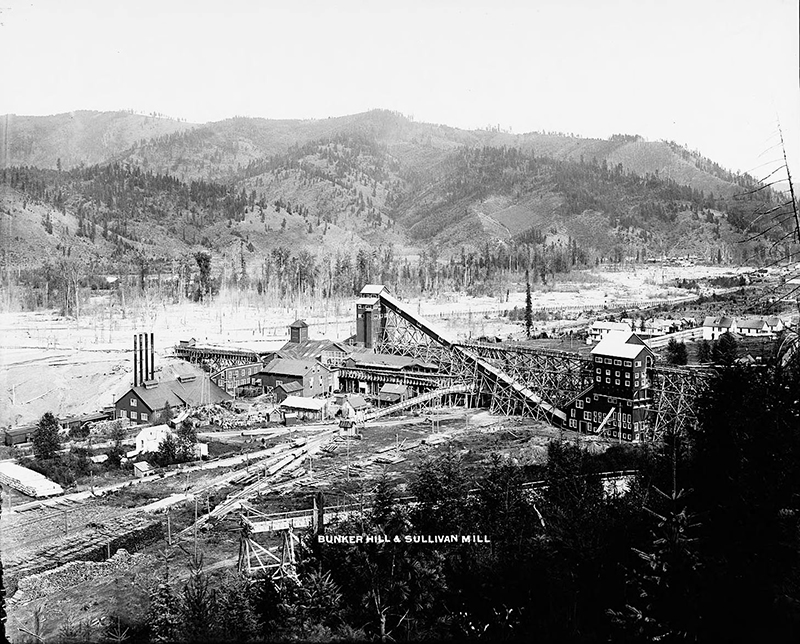

The building had been constructed by the Bunker Hill Mining Company in 1910. At the time, Kellogg’s population of 1,273 made it the smallest community in the world to have this kind of building. The three-story brick structure boasted a magnificent interior, comparable to YMCA buildings in Portland, Seattle, and Boise. It housed a gymnasium, locker rooms, swimming pool, boxing ring, game room, reading room, and even a four-lane bowling alley.

The old Kellogg YMCA building. Google Maps.

The YMCA in its heyday.

Bunker Hill and Sullivan Mine, 1904. U of I Digital Archives.

Playing volleyball.

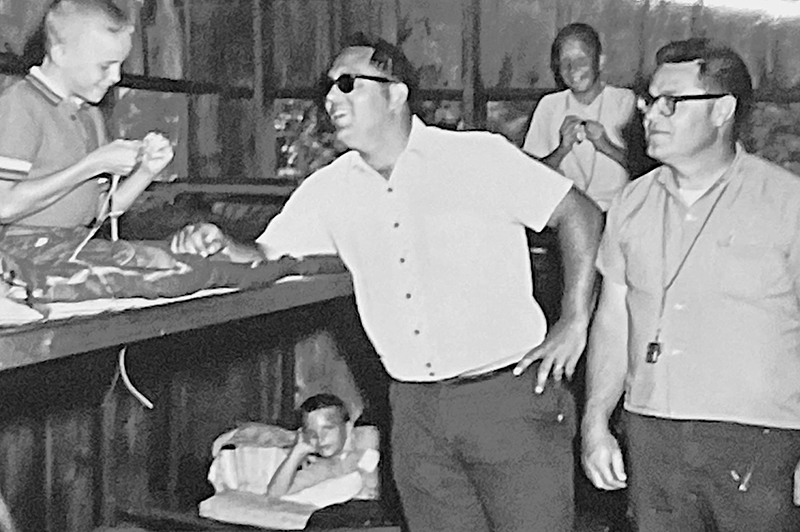

At the summer camp.

Teaching children to swim.

In the weight room.

It provided recreation and entertainment for the mine employees and families. If they joined, a small fee was taken from their checks monthly. In 1960, the amount was $1.50 per month or $18 per year. Anyone in the community could also join and pay the same amount. Around that time, many other large mining companies throughout the nation developed similar activity centers to support their employees.

The 1960s was a great period for Kellogg and the surrounding area. It was truly a blue collar town whose population of 5,061 was mostly employed by mines in the Coeur d’Alene Mining District. Almost everyone in Kellogg had jobs, but few were rich. Sports were in their heyday in a town whose high school basketball and football teams won against the best in the state and in eastern Washington.

The 1959 Kellogg High School basketball team was recognized by its coach, Ed Heimstra, and others as possibly the best team in the history of the sport in Idaho. Years later, the members of that team received the Idaho High School Activities Association’s highest honor, Legends of the Game. In an interview during the award event, Jeff Wombolt, who was the team’s second-highest scorer, recognized that the state champs of 1953-‘54 from Kellogg had started the legacy but also said the YMCA deserved credit. “Every kid I knew lived in that gym.”

Given such a legacy, I felt I had found the perfect place for my first job after college. Almost to a person, folks were kind and supportive. Many were very proud of their community and of their ethnic backgrounds, most of them having come from such European countries as Poland, Ireland, and Italy.

The history of the YMCA as an institution goes back to the late 1800s in London. During the Industrial Revolution, the Young Men’s Christian Association was formed to provide reading rooms as an alternative to saloons and other dubious hangouts. Over time, sports and exercise were added to the reading room, and people throughout the community were welcomed.

The Kellogg building was always busy in all its areas. The gym rats, as the kids were known, not only filled the gym but spilled over into other parts of the facility. We employees also supervised the city’s recreation program, a summer camp over Dobson Pass seven miles north of Wallace, and a complete night school. Classes ranged from oil painting to journeyman training in trades such as electricity and plumbing. The YMCA stayed open long hours to help accommodate miners on all three shifts, as many of the mines never shut down.

The Bunker Hill company, a strong supporter of families of the community, was known fondly as Uncle Bunker [see “Uncle Bunker,” IDAHO magazine, September 2021]. In the late 1950s, the Bunker Hill Mine was the largest industrial employer in the state. Its lead smelter was the biggest in the world.

Besides building the YMCA, the company provided up to fifty percent of its operating cost. It helped build the public swimming pool and sports stadium, with a roof over the bleachers. The company purchased and operated an electrical power plant that provided the community with its first electric lights. It provided a domestic water system, constructed the first hospital, and later built Lincoln Elementary School. It maintained a boarding house for many of the miners and strongly supported students with summer jobs and scholarships.

The Bunker Hill employment office was located in the YMCA building. It had a separate entrance but company employees or their spouses could pick up their weekly checks at the Y’s front desk.

In 1968, the company was purchased by Gulf Resources of Texas and future support for the YMCA became unclear. This was a major reason why I decided to end my employment there and return to my hometown of Boise to teach special education.

The YMCA operated for more than seventy years before Bunker Hill closed down the mine in 1982. Financial support for the YMCA then plummeted, the city’s population declined, and the building closed. It was sold several times and a few groups expressed interest in using it but such efforts failed. Community groups attempted to revive the YMCA program, but that also proved to be unsuccessful.

Last year there was still hope that the county might initiate federal funding to eventually save the building through the Historic Preservation Act. In any case, people who are old enough to remember the YMCA still praise the truly unique contribution it made to such a small community.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only