No products in the cart.

Summer Idylls

Grazing the Sheep

By Richard W. Etulain

The following excerpt, used with permission from the author’s new book, Boyhood among the Woolies, describes summers when the Etulains left their eastern Washington ranch to graze their sheep in the Idaho mountains.

We lived summers in St. Maries from before my recall through the early fall of 1944. After that and once Dad began to cut down on his sheep ranching and replace his sheep with more cattle, we did not need to take our smaller bands of sheep to the mountains for summer grazing.

When Dad first began taking his own sheep to the mountains between Calder and Herrick, he was building on family tradition. In fact, he may even have herded some of his uncle Martin’s sheep in the Bitterroot Mountains before having his own sheep. Dad’s older brother, Uncle Juan, also began to take his sheep to the mountains near St. Maries about the same time as Dad.

Our modest house in St. Maries, located at 332 South 11th Street on a hill two or three blocks south of Main Street, was our home for three to four months each summer. The rest of the year it was rented out. When we arrived, Dad and Mom spent a good deal of time and energy cleaning up after the renters and filling the basement back-in area with supplies for sheep camps in the mountains. Dad’s pickup was often backed down to this basement area and loaded with food for the herders and dogs.

The trips up to the mountains to contact the herders of the three to four bands occurred every week, sometimes more than once each week. There were six to eight men with the three or four bands, and a total of as many as fifteen to twenty dogs. It was about twenty-five miles from St. Maries to Calder, via the St. Joe River Road or Forest Highway 50. Dad crossed the St. Joe River at Calder and drove another eight miles on the North Side Road along the St. Joe over to Herrick.

Usually the herder or more likely the camptender brought down the packhorses and mules at the agreed-upon time, and Dad transferred the week’s supplies from his pickup to the worker, who returned to his band with the stores. The three to four bands totaled anywhere from six thousand to eight thousand sheep plus an equal number of lambs.

The land Dad used for grazing, some owned and some rented, stretched from Calder to Herrick. Traveling between these two towns, neither of which boasted a hundred residents, we crossed over Elk Creek and came to Big Creek on the western edge of Herrick. Dad’s bands moved about a good deal in the summer but remained in the mountains to the north of the St. Joe River. Often our main stop would be a thrown-together cabin near Herrick, where the mice and pack rats for most of the year took up residence when herders were not there.

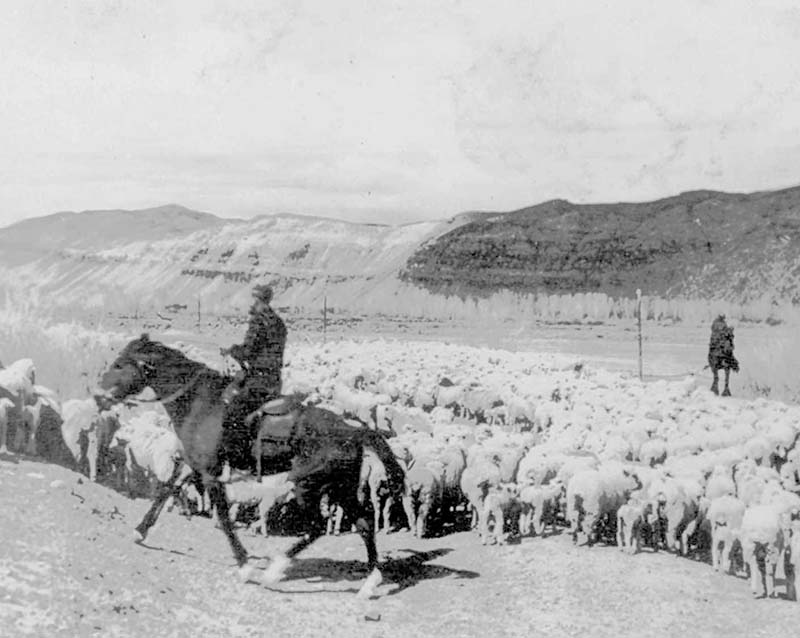

Sheep in central Idaho, circa 1920. Water Archives.

The Etulain summer home in St. Maries. Courtesy Richard Etulain.

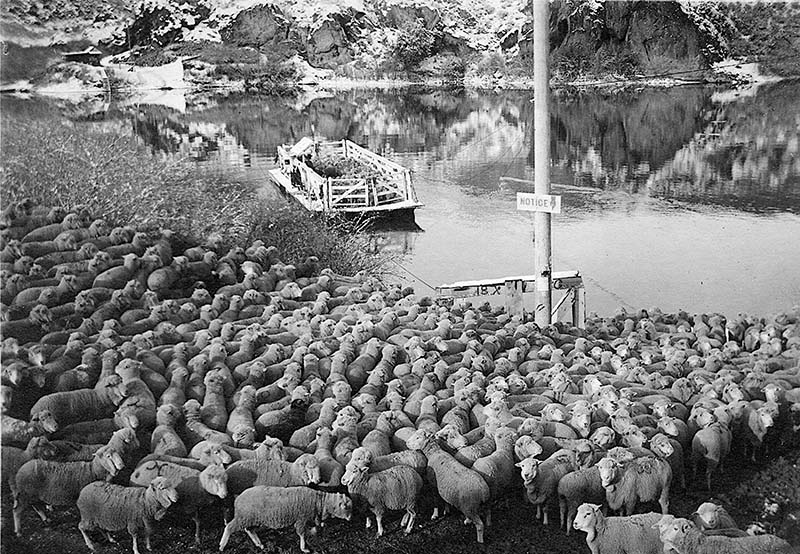

Sheep at an Idaho ferry crossing, circa 1915. Water Archives.

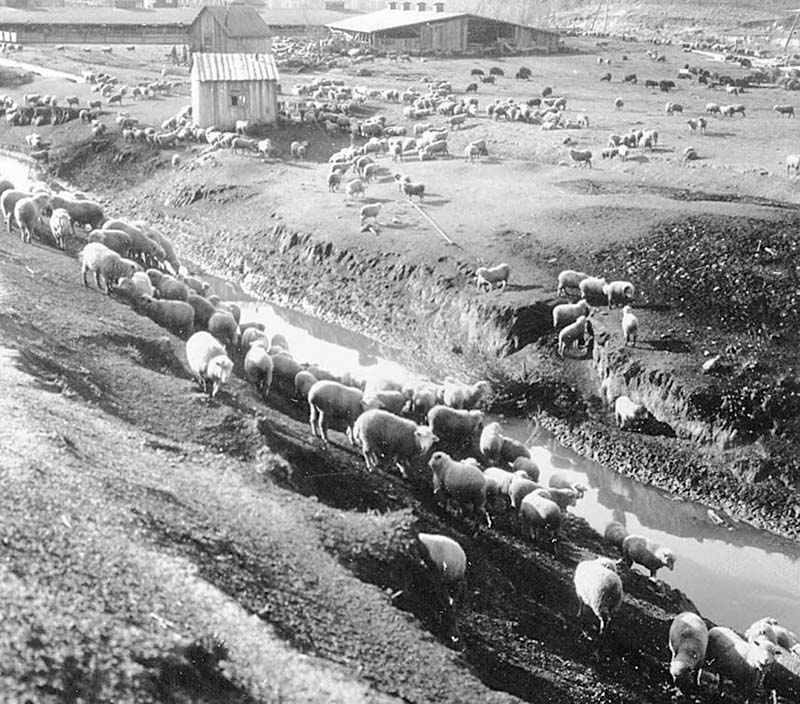

Idaho sheep and cattle ranch, 1915. Water Archives.

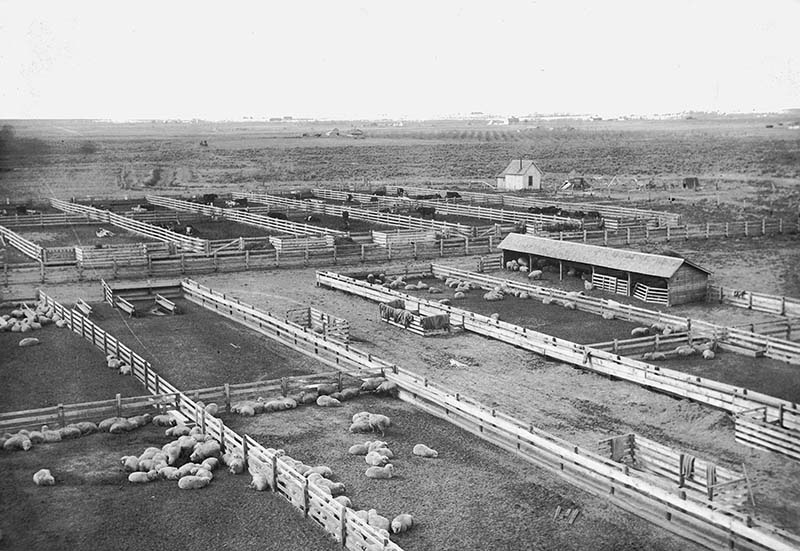

Idaho postcard photo, circa 1940. Water Archives.

Our neighbors in St. Maries included a local luminary or two. Just down and across the street in front of our house was the attractive brick home of Dr. C. A. Robins at 245 South 11th Street. He was our family doctor. He took out our tonsils and fed us soft cold ice cream to calm the upset. Dr. Robins became active in local politics, grew known in northern Idaho, and was elected Idaho governor from 1947 to 1951.

He was a staunch Republican, making him all the more laudable to my died-in-the-wool Republican parents. Across the alley from our back door was the Critzer family. Mr. Critzer was known throughout St. Maries as the leading train wrecker operator on the Milwaukee Road railroad that was so important to the town—and to the Etulains.

On one unusual day, the phone rang in our summer home in St. Maries. When Mom answered, the caller’s voice blurted out, “Your boys are down here in the main street without their clothes. Are they trying to be nudists?” Well, Mom remembered that story ever after. She told it again and again. It happened in our preschool days—earlier than our memories stretch back to.

As we got older, Mom, very busy as usual, allowed her three sons to roam around St. Maries. We hung out down on the docks of the St. Joe River, frequented the swimming pool in the park about five blocks away, ganged up with the neighborhood Osure and Demichael guys as often as we could.

On our way down to feast on ice cream at the Handi Corner on Main Street we would sometimes visit upon others our youthful, religious bias. Passing the Catholic school, we would yell out at the “Catlickers,” and they would yell back, “Doglickers.”

Our days and weeks in St. Maries were usually ones of leisure—fun, mainly. Since we were not on The Ranch, needed chores were not looming, and Dad seemed too busy to find something for us to do. So, off we went, to the swimming holes, running with chums, and haunting the downtown area. Sundays, of course, were church days—at the very small, rustic Church of the Nazarene down the street from us.

Some of my earliest St. Maries memories were crying about something in the earth-surrounded basement of Sunday School classes. Equally early were the vague memories of walking down the street with Mom and Danny to the nursery school and other preschools.

On a few occasions, we got out of town. One of our favorite outings was a Sunday afternoon picnic on the shores of Lake Coeur d’Alene a few miles north of St. Maries. At the Rocky Point beach, Mom unpacked a big lunch and Dad snoozed under the shade trees while we boys got into water fights along and around the docks.

Sometimes we ventured a bit farther north and turned in at Chatcolet for other beach adventures. Even less frequently, we would drive a few miles south of St. Maries to visit Uncle Juan and Aunt Margaret—before they were blessed with two daughters, Bonita and Arnola.

Summers in St. Maries ended in a rush. Up at Herrick, Dad loaded up the lambs, wethers (castrated males), and older and barren ewes on the Milwaukee Road, boarded the train, and headed for Chicago. Along the way, Dad and other sheepmen played a game with buyers, hoping to win the game. In a stop in Aberdeen, South Dakota, the sheepmen loaded up their animals with water, hoping that it would increase the total weight of the sheep by the first market stop at the Twin Cities in Minnesota.

But the buyers knew the old trick. They ran the for-sale sheep around the sale yards until the excess liquid was lost one way or another. If the market prices were low in the Twin Cities, Dad and his sheep continued on to the historic Union Stockyards in Chicago. He was stuck with whatever the market would bear in Chicago to sell his sheep. He would go no farther east.

His return was a big deal for the Etulains. Down to the St. Maries railroad station we went to celebrate upon his arrival. He had promised, for the future, that as soon as we were old enough, he would take us on the trip east with the sheep. Sadly, things changed in the sheep-raising world, and the trip never happened.

Even before Dad returned from selling his sheep, we would begin packing. Soon all of us, with the car and pickup loaded, would be heading back to The Ranch in the eastern Washington outback. The summer town guys were again returning to the range country.

Richard W. Etulain’s Boyhood among the Woolies: Growing Up on a Basque Sheep Ranch (Basalt Books, 2023) is available through bookstores nationwide, directly from Basalt Books at 800-354-7360, or online at basaltbooks.wsu.edu.

If you enjoyed this story, please consider supporting us with a SUBSCRIPTION to our print edition, delivered monthly to your doorstep.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only