No products in the cart.

The Freighter

Stories of the Old Stites Stage Road

By Billy Jim Wilson

Photos Courtesy of Billy Jim Wilson

Early last spring, my youngest grandson, Jesse Shreve, and his girlfriend, Tracy Buchanan, rented a place north-northeast of Grangeville, off Lukes Gulch Road.

Looking at my Idaho Atlas and Gazetteer, I noticed another road going north from Grangeville, named “Old Stites Stage Road.” A light went on in my head—this must be the route my maternal grandfather, William Ellis McGaffee, followed when he was hauling freight to White Bird and Slate Creek for the Salmon River Stores Company of Thomas Pogue.

William E. “Billy” McGaffee was born near Ione, in Amador County, Calif., on November 17, 1879. He came with his parents and siblings to Grangeville in the summer of 1883, before he turned four. His father, John Sybile McGaffee, is reputed to have operated the first steam-driven thresher on the Camas Prairie. John Sybile bought a house on the north edge of Grangeville. Sometime in the late 1980s, before my mother, Murrielle McGaffee Wilson, lost her sight, she typed up for my brothers and me many of the stories she’d heard from her father. Here’s her account of how Billy got his early training to be a teamster:

When Billy was ten and Fred [his next older brother] was twelve, their father had just returned from a trip, and at breakfast the next morning he told them,‘There’s a team of black mares in the barn lot. They are yours if you can break them to work.’ The boys rushed out to the barn lot as soon as breakfast was eaten, and sure enough two young black work mares stood with halters on. They started working with the mares, currying, brushing, talking and, of course, giving them a little feed of oats.

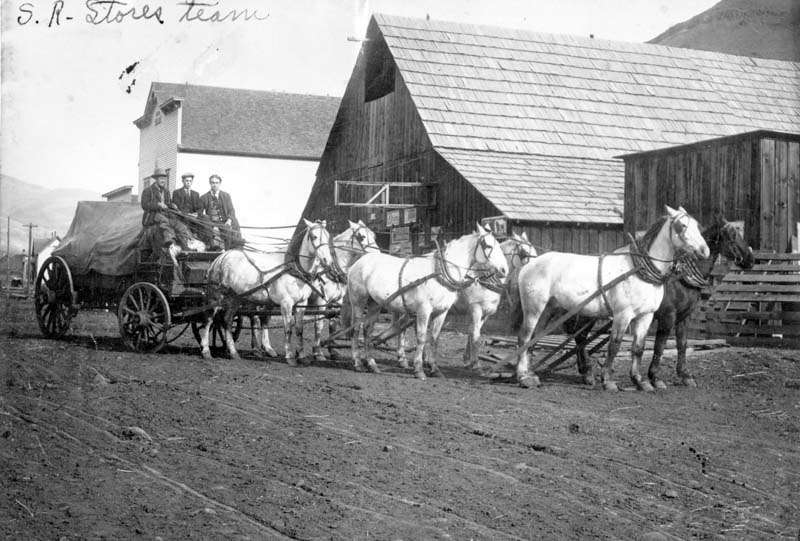

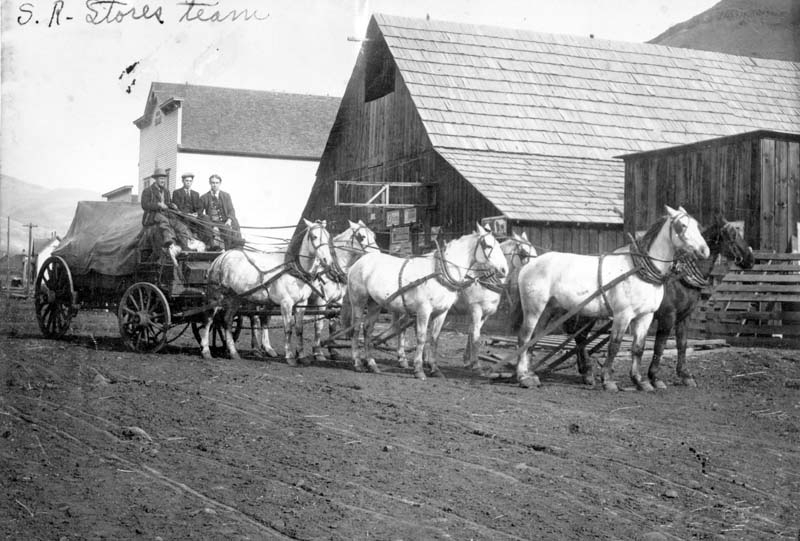

Salmon River Stores Company freight wagon and team in front of a barn in White Bird.

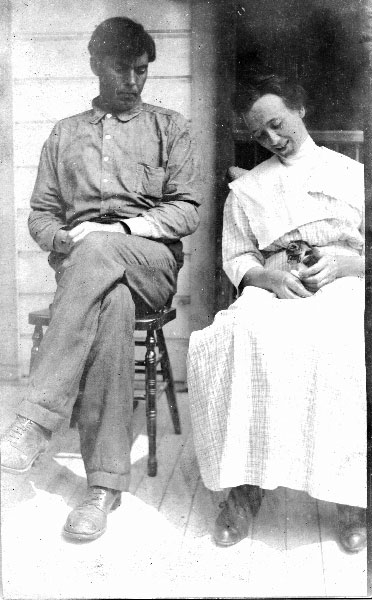

Billy and Mabel McGaffee at home in White Bird, circa 1911.

Mabel Holcomb (at right in doorway) at Freedom School with her class.

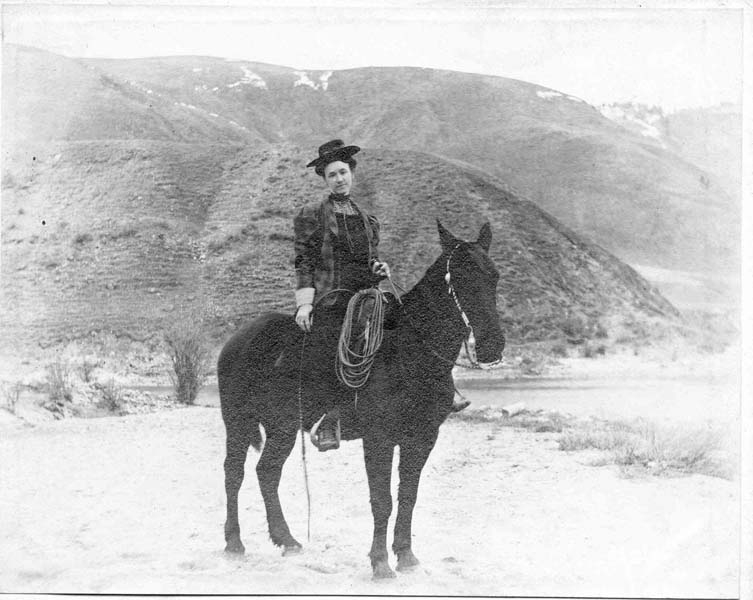

Mabel riding Brownie at Slate Creek, circa 1909.

It took them most of the morning to get the harness on, but eventually they did, and backed the mares up to a light spring wagon that stood in the lot. Billy stood at their heads, holding firm to the headstalls, while Fred climbed into the wagon and got the reins wrapped around his hands. Then he hollered, ‘Open the gate, Bill!’

Billy swung the gate wide, Fred loosened the reins, and the mares took off at a wild gallop, Billy swinging up over the tailgate as it went by.

They had miles and miles of prairie to run on, with no fences. When they tired, Fred turned them back for home. This procedure was kept up until the mares gave up their wild running and were ready to be trained to back and turn, and other things a work horse needed to know.

Billy and Fred continued using their skills as teamsters, hauling things with their own team and wagon, or hiring out to drive for someone else. As my mother tells it:

Fred had a job that spring [1896] driving the mail from Mount Idaho to Florence. Soon after he started this job, he came down with typhoid and was ill most of the summer. Billy took over the mail job [at age 16].

Now and then he had passengers going in to the mines, or coming out. One such passenger was a woman, heavily pregnant, who was going into town to have the baby. He had to stop quite frequently to let her get down and go into the brush to relieve herself. When he delivered her safely to Mount Idaho, someone who saw her get off asked jokingly if he wasn’t nervous about her having the baby on the way in.

He replied seriously, ‘Oh, no, she wasn’t due for another week, she said,’ and wondered why the man laughed. He didn’t learn until sometime later that babies can come any time, and a week isn’t a very good margin of safety.

Flora Mabel Holcomb was born on her father’s farm near Royalton, Wisconsin, on March 18, 1879. She was the fifth of eleven children, mostly girls. Their father died when Mabel was seventeen. An aunt offered to help them through normal school. Mabel and her next younger sis, Lee, took up the offer. They taught for several years around Wisconsin, but after about ten years Mabel wanted to go west. It was 1908. As my mother relates it:

Mabel signed a contract to teach at Fort Freedom that first year, and traveled by stage from Grangeville to Freedom [now Slate Creek]. The road was slow and scary and the driver told her gruesome tales about early-day holdups and such. She had grown up in relatively flat country, so the deep canyons were daunting.

The stage pulled up in front of the hotel about suppertime. Mabel noted as she climbed down a young man tanned like a coffee berry with a waxed moustache, black hair and eyes, and thought, ‘I must remember to write the girls I’ve seen my first Indian.’

Growing up in Riggins, and traveling occasionally to Lewiston along U.S. 95, I always assumed that Grandmother must have come from Lewiston to Grangeville by stagecoach. No one ever said, and I didn’t think to ask. Now that I’ve discovered the dates that the railroad came to Stites, and when it came across the Camas Prairie to Grangeville, I realize that Grandmother in the summer of 1908 must have ridden the train to Stites and taken the stage to Grangeville over the Old Stites Stage Road, the same route that Grandad freighted over.

As elsewhere in the Pacific Northwest, the Northern Pacific Railroad and the Union Pacific Railroad were often in contention for rail service to remote areas. This was the case with Grangeville. But by 1899, the Northern Pacific had built a line up the Clearwater River to Sites. That soon curtailed staging from Lewiston via Waha and Cottonwood to Grangeville. When the railroad reached Stites, the staging company began providing service between Stites and Grangeville, about twenty-one miles.

That route was soon swamped. A September 14, 1902 article from the Lewiston Tribune, quoted in the 1971 Pioneer Days in Idaho County, reported, “The stage road between Grangeville and Stites is literally packed everyday with teams engaged in hauling freight from the rail terminus to towns on Camas Prairie. Thousands of tons are handled weekly.”

But work was afoot to build the Camas Prairie Railroad, extending the line from Culdesac via Craigmont and Cottonwood to Grangeville. The first train to travel that route arrived in Grangeville on “that memorable day of December 9, 1908,” as Sister M. Alfreda Elsensohn put it in Pioneer Days in Idaho County.

Last September, this route was further authenticated by a mining report for sale on eBay. The report indicated that in late fall of 1901, a New York firm hired two men from Spokane to visit the Seven Devils Mining District and advise them regarding investment potential there. The report contained four pages of text and five pages of photos illustrating the mountainous character of the location. The text, which described the investigators’ travel arrangements, emphasized the region’s near-inaccessibility.

The investigators left Spokane on November 13, 1901, spent the night in Lewiston, and reached Stites by 11:30 the next morning. At noon they left Stites by stage, arriving in Grangeville, seventeen miles distant, at 7 p.m. The next morning, they left Grangeville at 6:45,reaching Goff (at the mouth of Race Creek, about one mile north of Riggins, which is fifty-two miles from Grangeville), at 7:30 p.m. They left Goff at 8:30 a.m. and two hours later reached Pollock, six miles away. From Pollock, they switched to horseback and followed a trail up Rapid River. Their recommendation concerning investment was not positive, because of the accessibility problem.

Not long after Mabel’s arrival at Fort Freedom, she learned more about the young man who looked to her like an Indian, but proved not to be. Again, as my mother tells it:

She soon discovered he was the clerk at the little store nearby, named Billy McGaffee. She also noted a good many cowboys visiting on the porch, who either ate supper at the hotel or rode away as soon as the stage was unloaded. A great many errands were executed the day the new schoolteacher arrived, which she did not realize the significance of until many years later. She boarded at the hotel, as did Billy.

Billy started squiring her around, teaching her to ride his gentle Brownie horse. (The hotel-keeper lent her a divided skirt.) A picture of her mounted on a western saddle went home to show the other girls. There were many young men in the area, and I’m sure they all gave her a whirl, partly to tease Billy, partly for her own charms. She was too modest to say so but that was the way things were—the new schoolteacher was a real challenge.

After the Camas Prairie Railroad’s first train arrived at Grangeville in December 1908, I expect Billy McGaffee only freighted from Grangeville to White Bird and Slate Creek. The new Union Pacific route up from Culdesac and across Camas Prairie ended the need to haul freight on the road from Stites. The next spring, while taking a load of freight to Slate Creek, Billy was in an accident. As Mom tells it:

One June day in 1909 he drove onto the bridge at Skookumchuck [Creek] with a heavy load and the six horses. The stringers on one side of the bridge broke, flipping the loaded wagon upside down into the creek below. Billy fell about twenty feet, landing on his head in the rocks. But he managed to get up, cut his team loose from the wreckage, and from each other, and get them and himself up to level ground.

Mrs. Reid, who lived in a log cabin nearby had heard the crash and rushed up. She had a dishtowel in her hand, and wrapped it around the cut on his head, saying, ‘Billy, you’re hurt!’

When Billy saw the blood on the dishtowel, he fainted. She called her sons from the field to pack him into the house and sent for Doctor Foskett in White Bird. The ligaments in one knee were torn, and his neck swelled up as big as his head. He probably had some cracked ribs, but otherwise [was] not too seriously hurt.

Doctor Foskett said, ‘Billy, if you didn’t have a neck like a bull it would have been broken sure.’

They hired another teamster while he was recuperating, and when he was able to go back to work he went to clerking in the White Bird store until he recovered his full strength. Then he freighted for another year. He got married that Christmas [1909].

In the spring of 1961, I was living in Grangeville and about to get married to my first wife, Jonna Wright. My McGaffee grandparents, who were getting up in years and had celebrated their fifty-first anniversary the previous Christmas of 1960, were reminded of when they got married at the old LaFrance Hotel in Lewiston on December 25, 1909. Grandad said he was making ninety dollars a month as a freighter, which was big money in those days, and that he paid ten dollars a month rent for a fairly nice house in White Bird. As I remember it, he told of hauling the freight for Pogue’s Salmon River Stores from the railroad at Stites to Grangeville and over White Bird Hill to White Bird, and even on to Slate Creek.

He also told me, with a twinkle in his eye, that Pogue really liked having him do the freighting, because he didn’t drink alcohol. It seems that most freighters were usually pretty heavy drinkers, and if there was a keg of whiskey or other alcohol in the freight shipment, they would place it on the wagon seat for a while, stick their knife between the staves, and use a pan to catch the drippings. By the time they got to their destination, they’d be thoroughly drunk.

It was one way for a freighter to while away the long distances, but it sure cut into the owner’s profits.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only