No products in the cart.

The Hermit Sculptor

Call Him Markham Schimmelhoeffer

Story and Photos by F.A. Loomis

An Idaho hermit artist I know reminds me in his manner of the famous Buckskin Bill, whom I met when I was in high school. I was a box boy in a McCall grocery store and Billy—on one of his summertime grocery procurement flights out of the wilderness—was in the condiments aisle buying pickles. He was friendly, jovial, and talkative—but he smelled atrocious!

This artist is friendly but doesn’t smell awful. A talented sculptor, he’s well-groomed and always sports a good-looking Stetson on the rare times when he’s public. Like Buckskin Bill, he’s full of quips and musings around people. He simply prefers to live privately, in near-isolation deep in Idaho timber country.

He has a truck, a tractor, a snow blower, and a generator, yet his home and woodshop are surrounded by big game and such smaller critters as raccoons and foxes, plus a variety of birds. He has a large library, art gallery, and a bunker-style armory. For entertainment, he watches reruns on Turner Classic Movies.

I met him about six years ago at his wife’s funeral, which I managed as a deacon. Her history was remarkable: her family survived the Japanese occupation of Malaya during WWII. She was the cook in the family, so he now lives with a deep freezer full of TV dinners.

Amusingly, this recluse asked to be referred to in the story as Markham Schimmelhoeffer. He’s eighty-five years old, has lived in the woods for more than thirty years, and when I asked if he might like my help to arrange a public show of his big game sculptures, he said, “Don’t even think about it. You know how good a shot I am with my Weatherby.”

Then he winked. I was only mildly intimidated, but dropped the idea. His Weatherby is a Mark V .460 Magnum—for all practical purposes, an elephant gun.

Buckskin Bill. Courtesy Western River Expeditions.

The artist known as Markham.

Angry water buffalo.

An African goat ram.

Cougar pursue deer.

Battle of the elks.

Wolf and moose.

One of Markham's paintings.

Lunging water buffalo.

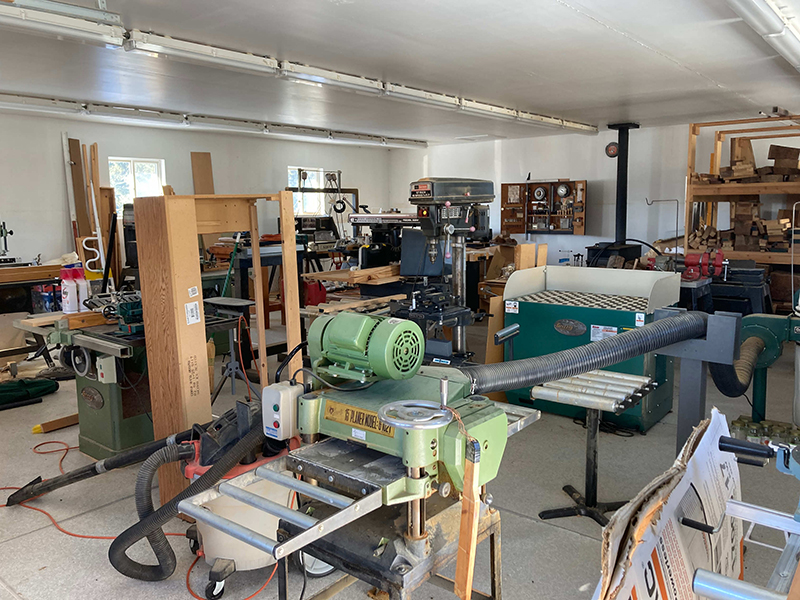

Markham's well-outfitted woodshop.

Markham’s arsenal reflects a long military and police history. He was born in Michigan, where he went hunting as a boy, but he never shot a deer during hunting season because he said whenever he saw one, he was too close to a highway. He later joined the Marines and served for a decade in Japan, Taiwan, and Vietnam. He became a field officer with the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department, where he worked for twenty-three years.

During the 1990s, he began to paint mountain scenes with oils but was disappointed by two-dimensional art. He turned to wood carvings of animals, and explored the characteristics of different hardwoods. He learned quickly that walnut was the finest hardwood available for the big projects he planned, because its grain was consistently very hard. Other hardwoods, he discovered, could have irregular, soft seams. He soon put together an extensive shop of woodworking tools.

“My first sculpture of a moose was embarrassing in many respects,” he told me, “but it was a great lesson and I slowly learned the reduction process for modeling subjects and objects.”

Markham continued to study the complexities of shaping wood. He’d start a project without strong feelings but would finish in intense excitement, as his tools began to reveal the flexing of muscles and the twitches of big game animals. “Even my water started to look like it was actually flowing,” he said.

A few years after moving to Idaho in 2008, he went on a twenty-one-day trip to South Africa, where he experienced big game hunting on a scale beyond anything he had imagined. The meat from the hunt was refrigerated in mobile units that accompanied the hunters and was donated to charity.

Markham told me the recipients of the meat thanked him, as did the conservation managers for helping them thin out wilderness herds, which they said would have suffered starvation in the absence of culling.

While he never went back to hunting big game, the hunt changed his artistic life. He became increasingly active in sculpting large game animals in natural settings with water and vegetation. He also experimented with etching big game and veldt on warthog tusk— but he told me that was almost as two-dimensional as painting and the material was too soft.

His deep-woods home is filled with hardwood scenes of black rhinos, elephants, cougars, kudus, water buffalo, bison, elk, bears, and lions. The scenes include predator chases, animals sauntering at sunset, ferocious posturing, mating courtship, and showdowns during mating season.

At a time when many artists seek authentication from peers, a few go their own way, in a tradition that hearkens back to Dugout Dick’s poetry or Buckskin Bill’s hand-crafted shooting irons. Dugout Dick was Richard Zimmerman, originally from Indiana [see “Dugout Dick,” IDAHO magazine, May 2010]. He lived in a cave near Salmon for nearly sixty years.

Buckskin Bill was Sylvan Ambrose Hart, more of a roamer, originally from the Oklahoma Territory before it became a state. Skilled as a gunsmith, Bill lived most of his life on Five Mile Bar along the main Salmon River.

Markham is a man of dry humor who likes to tell the same jokes over and over again. While he doesn’t hunt anymore or even do much woodwork because of his age, he still reads about woodcraft technology and wild game artists. He also periodically checks on his arsenal in an underground vault, and nostalgically recalls the days when he used certain firearms.

His favorite hunting piece was a Weatherby Athena semiautomatic twelve-gauge shotgun for upland game birds. I don’t hunt anymore, either, although maybe someday I’ll acquire an F.A. Loomis IXL 40 twelve-gauge shotgun.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only

One Response to The Hermit Sculptor

Clark Ballard -

at

Outstanding story F.A. Fascinating information about a fascinating man. I really appreciate articles that are well crafted. Thank you, from an old Idaho native.