No products in the cart.

The Spiral Highway

My Turn to Drive

By Mark Ready

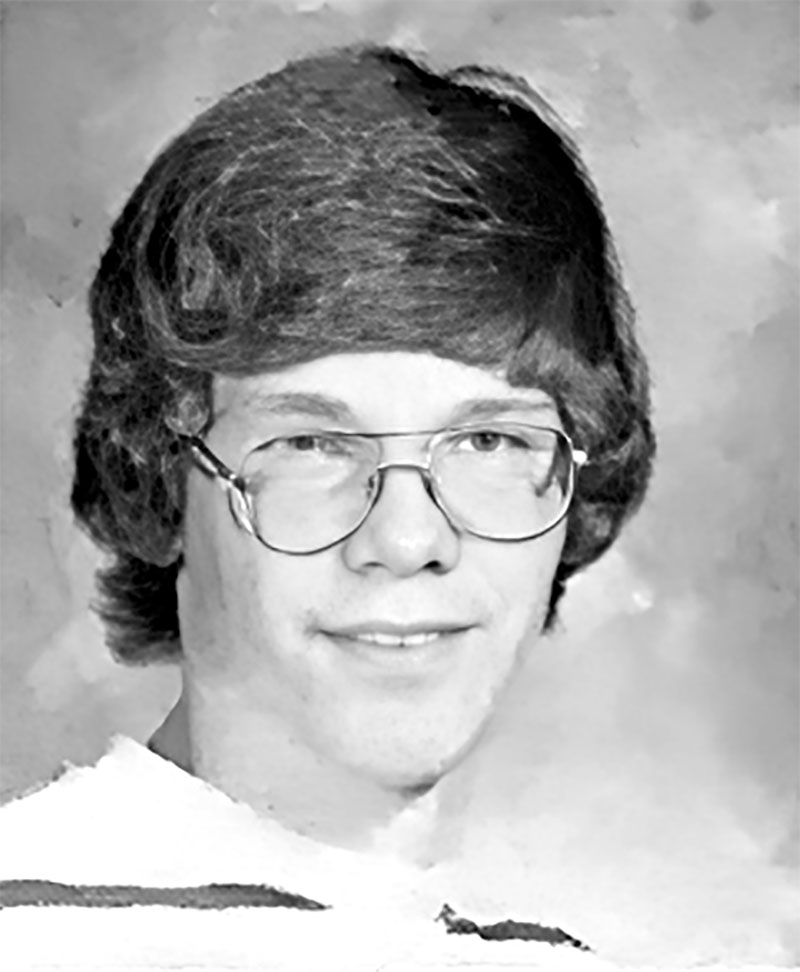

In 1976, as the United States celebrated its Bicentennial, I was a fourteen-year-old in Lewiston, sitting behind the wheel of a brand-new Chevy Camaro. My driver’s education instructor was Richard Hager, a man whose black plastic-rimmed glasses and mild-mannered junior high school teacher persona hid nerves of steel.

He slid into the seat beside me, armed only with a passenger-side brake that we called a chicken brake and a clipboard. He familiarized me with the mirrors, brakes, throttle, and turn signals and directed me to pull away from the curb. The brave man’s first advice was to use only my right foot for the gas and the brake.

My pappy said, “Son, you’re gonna drive me to drinkin’ if you don’t stop drivin’ that hot rod Lincoln.”

The rockabilly riff of the iconic American song went through my head, accented with whines and squeals that mimicked the sounds of a powerful engine, skidding tires, and a horn saying get out of my way.

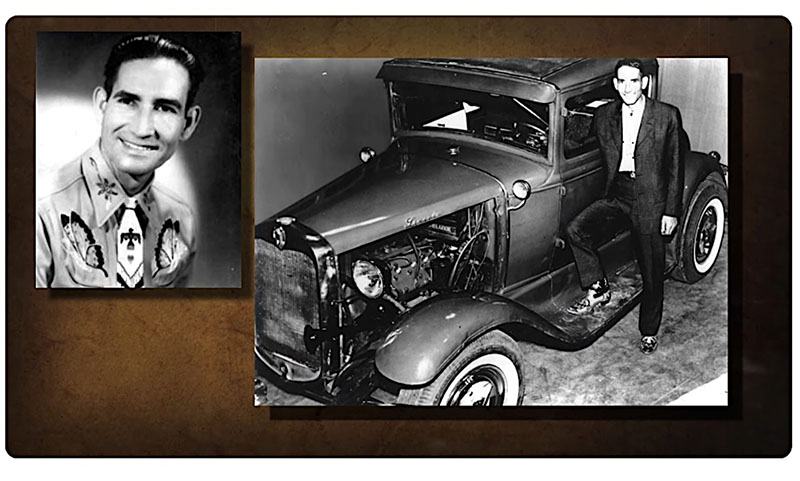

Five years earlier, country rock band Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen had released a version of “Hot Rod Lincoln” that reached number nine on the Billboard Hot 100. Charlie Ryan and W.S. Stevenson wrote the hit song, which Charlie first recorded in 1953.

One verse goes:

Pulled out of San Pedro late one night

The moon and the stars was shinin’ bright

We was drivin’ up Grapevine Hill

Passing cars like they was standing still

Except it wasn’t San Pedro and it wasn’t Grapevine Hill. After David Johnson interviewed Charlie Ryan for the Lewiston Tribune, he wrote, “Ryan recites the lyrics as he recalls the race. The friend drove a Cadillac and Ryan was behind the wheel of a 1941 four-door Lincoln sedan with a twelve-cylinder engine.”

Charlie and his band, the Livingston Brothers, traveled to Lewiston from Spokane in the 1950s to play at the Paradise Club. After one of their gigs, a friend passed him in his Cadillac and disappeared over the top of the old Lewiston Hill so fast it inspired him to write the rockabilly ballad. Interestingly, George Frayne IV, alias Commander Cody, was born in Boise on July 19, 1944.

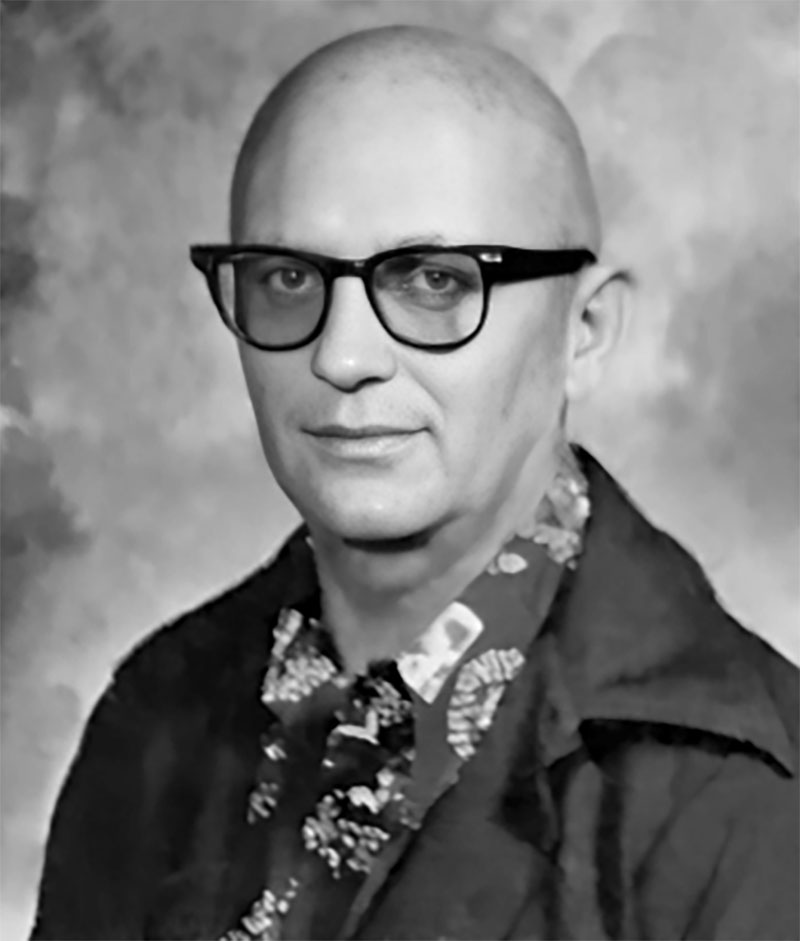

Mr. Hager’s counterpart for my classroom studies at Jennifer Junior High in Lewiston was Don Campbell. His calm outward appearance belied the strength of a superman who dealt with immature fourteen-year-old brains and the euphoric effects on them of gasoline fumes, teen hormones, youthful invulnerability, and access to an automobile.

I was surprised by the number of “D” students who got an “A” in driver’s education. Learning algebra, earth science, and social studies to become productive members of society had nothing on getting behind the wheel of a car.

Cassus C. VanArsdol. Courtesy Steven Branting.

Charlie Ryan and a hot rod. Courtesy Duane Becker.

Don Campbell. Courtesy Mark Ready.

The author at age fourteen. Courtesy Mark Ready.

Richard Hager. Courtesy Mark Ready.

The old Spiral Highway today. Rene Ready.

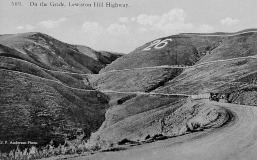

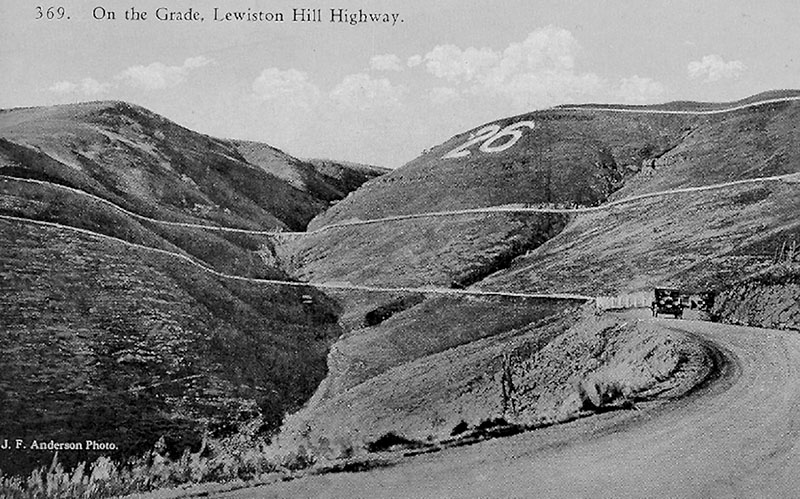

The highway in its heyday. Lewiston Historical Society.

I belonged then to a subset of the human species first categorized in the 1920s—teenagers. Scholarly articles list three factors pivotal to the advent of teen culture: compulsory education, the postwar boom, and the invention of the automobile. Access to a vehicle gave America the malt shop, submarine races, and Lookout Point.

If you cringe at the thought of a ninth- or tenth-grade boy behind the wheel of a car, don’t forget what the Good Book says: “Let he who is without sin cast the first stone.”

Driving at fourteen meant a daylight-only license. Science, the church, and a stick stuck in a circle in the dirt defined daylight but a fourteen-year-old’s interpretation of the word varied on how necessary it seemed to go somewhere and on their parents’ permissiveness.

Aside from the parental restriction, you were free to drive. The instant you passed the test, you could fill your car with friends and head to the beach. As for me, somebody needed to pay for that sweet juice of freedom, gasoline. So, I headed to work.

Farm boys and girls hauled the harvest to the elevator and drove the tractor out of necessity. My country cousins had been driving since they were old enough to look over the dashboard. My first time behind the wheel was in Uncle Rick’s hay field on the Camas Prairie when I was six or seven.

He’d slip the old orange-and-white 4WD International Harvester pickup into compound low, and I’d steer between the rows of baled hay as my older cousins loaded the lowboy trailer.

My childhood home of Lewiston is known as the Banana Belt and the Gateway to Hells Canyon, the deepest gorge in North America. The confluence of the Snake and Clearwater Rivers is the lowest point in the state, at only seven hundred and ten feet above sea level.

Because of this, the Lewis-Clark Valley is blessed with mild winters and long growing seasons. Perhaps the least appreciated aspect of Lewiston’s location is that every road through the state that arrives here is going downhill.

The growth of agriculture made vehicle access to rail and river transportation at the base of the hill a necessity. Nez Perce County engineer E. M. Booth surveyed a route for vehicles in 1914. His route primarily followed the ridge lines down the hill, which could be more accurately described as a massive basalt escarpment and part of the Columbia Plateau.

The Spiral Highway, which follows the survey’s route, uses sixty-four turns to cover the two-thousand-foot drop in elevation at an average grade of 4.68 percent. It was designed for speeds of twenty to thirty miles per hour.

Cassius C. VanArsdol engineered the grade and saw the project completed in 1917. He was a talented engineer who played a significant role in transportation development and worked for the Union Pacific and Northern Pacific Railroads. He founded the Lewiston Water & Power Company in 1895 to divert water from Asotin Creek to area farmers.

His home in Clarkston, across the river from Lewiston, started as a small cottage but was added to several times and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Sadly, the house has fallen into disrepair and is not habitable. Cassius is buried beside his wife, Della, at Lewiston’s Normal Hill Cemetery.

In my driver’s ed class, there were three of what you might call red-letter days. The first was learning to parallel park. The second was driving Main Street and the third was a trip up or down the Spiral Highway.

Every truck and auto traveling between Boise and Coeur d’Alene took the grade. It was a natural bottleneck and traffic was almost bumper-to-bumper. My older brother Joe did nothing but stoke my fears about how difficult and dangerous the hill could be.

If it hadn’t been for Mr. Hager’s quick tug on the steering wheel on the way up, my brother’s prophecies of doom would have come true. The first student to drive with us on the morning of my test concentrated on counting the cars he was holding up on the grade instead of watching the road.

The first and only time I saw Mr. Hager’s composure slip was when the Camaro began to head off one of the hairpin turns. It sure got my attention.

My turn to drive was going down the grade, which was narrow and intimidating, with little room for error. The huge trucks took every inch of their side of the roadway and I concentrated on staying in my lane and off the shoulder. The maximum speed was thirty-five miles per hour, with some corners rated twenty.

Average highway speeds were sixty-five, and many drivers ignored the signs and drove as fast as they could. I started breathing about halfway down and Mr. Hager told me to loosen my grip on the wheel, which was white-knuckled. Talk about a rite of passage.

In the early 1950s, people in Moscow proposed a replacement of the Spiral Highway with a route over the hill near Spalding. This so incensed Lewiston community leaders that they told the state highway board members they didn’t want a new grade if it bypassed the city.

The highway board took the area representatives at their word, and it wasn’t until the early 1960s that a serious effort was made to find a new route. After many years of study and compromises, construction on the new road started on July 28, 1975.

The grade, dedicated on October 28, 1977, cost more than twelve million dollars. More than 4.2 million cubic yards of rock were moved, and two thousand cubic yards of concrete were poured for the three-level interchange at the bottom. The road was covered with 4,372 tons of asphalt paving.

I remember watching it being built from Mr. Green’s eighth-grade classroom windows, back before that tantalizing glass wall was covered with plywood and sheathing in the name of energy efficiency. Rock chiseled from deep cuts filled the ravines as the new highway muscled its way up the hill. Gone were the curves.

The speed limit was raised to sixty miles per hour and truck ramps were strategically placed on the seven-percent grade in case semis lost their brakes on the way down.

The new grade is faster and easier to drive than the old one, but I still admire the graceful way what is now called the Old Spiral Highway meanders up the hill. It flows with nature. There are no massive cuts and fills like its replacement. It’s the year 1917 sculpted in basalt.

Thirty miles per hour was plenty fast for the teams of horses and automobiles that journeyed along it. You can’t beat its slow curves for a nice relaxing drive on a summer afternoon, and the view from the overlook at the top is spectacular, especially at sunset.

I see my fourteen-year-old self at the end of the Memorial Bridge on a hot summer night. I look north at the steady stream of headlights going down Highway 95 while the Spiral Highway is deserted to the west of it.

I’m standing by the ’76 Camaro and the ghosts of Mr. Hager, Mr. Campbell, and C.C. VanArsdol are beside me. I hear “Hot Rod Lincoln,” with Commander Cody a-singin’. Charlie Ryan steps out of his car, its engine a-ringin’.

“Climb in, gentlemen,” I say without blinkn’. “It’s my turn to drive this Hot Rod Lincoln.”

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only