No products in the cart.

They Called My Name

Borah, Church, and Donaldson Peaks

Story and Photos by Michael Stubbs

In 1984, I was five years old and living in Twin Falls. My family moved there the year I was born, so it was the only home I knew. My parents, however, were still getting to know the Gem State. My father, Mark Stubbs, volunteered as scoutmaster for a troop of boys sponsored by a local church congregation, and in his naiveté, he and another green scoutmaster, Brent Hyatt, decided to take their troop up Mount Borah for a Saturday climb in the fall. Both of these men were in their thirties, country boys from rural Utah. There was nothing they couldn’t handle. They loaded what my dad would refer to as a “motley crew” of teenagers into a station wagon and drove off to the Lost River Range.

Because I was five, I remember the story from a very limited point of view. I knew Dad had gone with his scouts to climb Idaho’s tallest mountain, but that didn’t have a lot of meaning to me. Saturday with Dad. It just sounded fun.

They didn’t have fun.

It was Saturday night. My mother was crying, and my older sister and brother wouldn’t let me ask her why.

The conversation went something like this:

“Because Dad’s not home yet, that’s why.”

“Is he at work?”

“No. He is still on the mountain.”

“What mountain?”

“Mount Borah!”

“Oh, yeah.”

“With the Boy Scouts.”

“Oh, yeah.”

I remember my mother pacing back and forth in front of the door that led from our family room to the garage. She wrung her hands. I remember her sitting at the kitchen table staring at the yellow phone on the kitchen wall as I went upstairs to bed. I wasn’t worried but I felt so bad for my mother, who clearly was.

Dad made it home sometime around two in the morning, which now, after years of my own mountain climbing experience, doesn’t sound too bad. I learned this from my older sister when I woke up and walked straight down the hall to my parents’ bedroom to see Dad. My sister stood guard at the door, making sure the younger kids didn’t disturb the man who was worn out from climbing Idaho’s tallest mountain.

My mother slipped in and out of the bedroom several times, barely opening the door a crack to do so. I couldn’t get a glimpse of my dad through the blockade of Mom, sister, and door. This frustrated me. I sat and waited on the stairs until no one was standing guard, and then let myself into the room, stood by my father’s side of the bed, and watched him sleep awhile.

Eventually, he stirred. Without opening his eyes, he said, “Hi, Mike.”

“Hi, Dad. Did you climb the mountain?”

“Yes. I need to rest now. I need to sleep. I’m very tired.”

“Did you make it to the top?”

“Yes. Let me rest now.”

“Dad?”

“Yes, son?”

“Will you take me to Borah one day?”

“Sure, son. Later though, okay?”

“Okay.”

Adam, Brady, and Dave on the ridge to Mount Church.

The author with children Jan and Eliza on Mount Borah, 2019. Troy Lindtvedt.

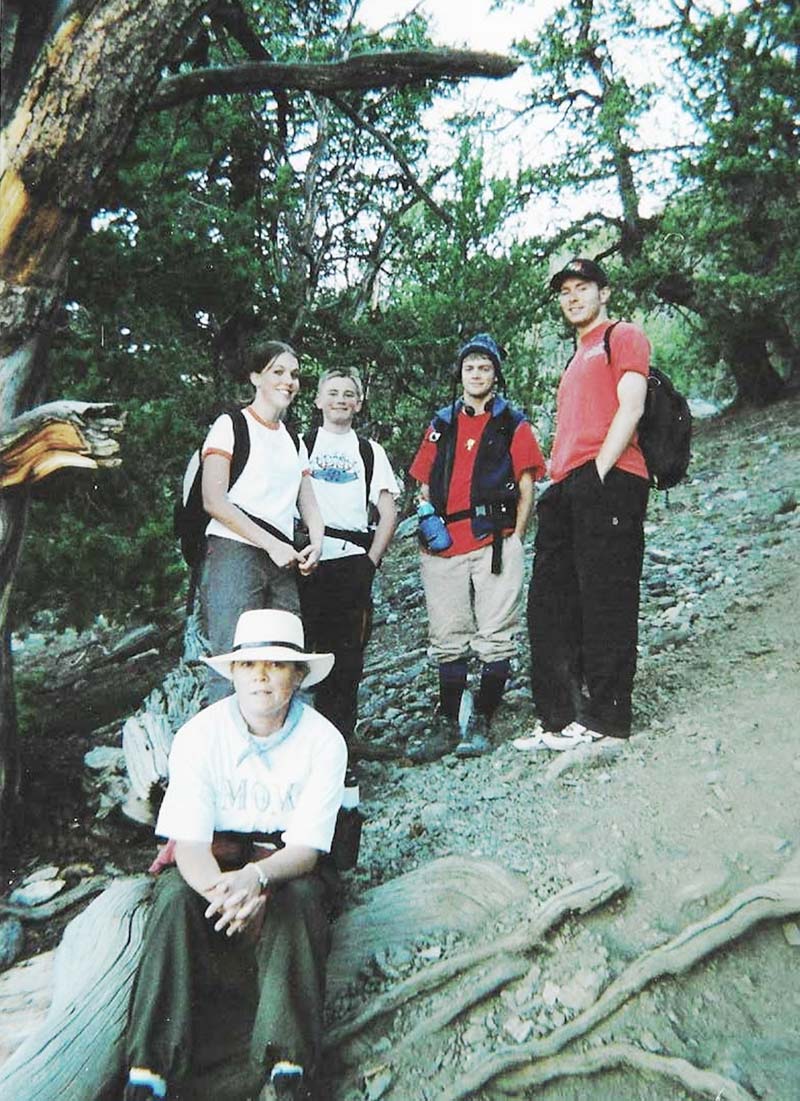

Family and friends on Borah. 2019. Mark Stubbs.

Brady contemplates the Donaldson/Church climb.

The crew on the ridge connecting Donaldson and Church.

The glacial bowl and pond and the cirque above it that separates Donaldson from Church.

Finn Stubbs and the author on Mount Borah's Chicken-Out Ridge. AdamChristensen.

Dave and Adam rest on the way up Donaldson/Church.

A Lost River Range sunset.

A drainage on the Donaldson/Church climb.

Michael's wife Wendy climbs Mount Borah.

My mother caught me and ushered me out of the room. I don’t remember the details perfectly but there were words like “strained” and “exhausted.” My mother told me over and over that Dad’s muscles hurt and he couldn’t pick me up or hold me. None of this bothered me as much as not being able to hear right away Dad’s story of climbing the mountain. I wanted to know how he climbed down it in the dark. I wanted to know why it took so long. I wanted to know how he hurt his muscles.

Over time, the story came out. Dad would tell us mini-stories about each of the Boy Scouts in his troop, boys we knew from church. Each had handled the mountain differently. A couple of healthy, athletic boys mostly ran to the top without their leaders or the others. They didn’t struggle. They had a fun climb. They summited and turned around to trot back down the mountain. They passed the other boys and my dad and Brent on their way. They had a long wait at the car for the rest of the troop. No big deal.

Other boys had tried to match pace with the fast boys and suffered. Borah was a more difficult mountain than they had anticipated. Dad shared stories of finding some of these boys sitting alone, hugging their knees, crying on the side of the mountain.

Dad and Brent made it to the top after their own tumultuous navigation of Chicken-Out Ridge. The name fascinated me. I couldn’t help but picture chickens. Chickens and rocks. The mystery of the mountain grew with my misconceptions, but Dad didn’t say much more than the names of the boys who reached the top, those who didn’t, and why. For him, it was a story of quitting or soldiering on. It was about facing fear and overcoming limitations or sitting down and giving up. It was about people, not a mountain.

Dad had fun mythologizing the drive and the name of the river and the mountains. He told us about the Lost River as if it were a mystery no one had yet solved.

“It just disappears into the desert!”

“It disappears?”

“Yes. It winds its way past the mountains that share its name, and then it turns toward the desert and sinks into the sand.”

“It sinks into the sand?”

“Yes.”

“Wow.”

I was a captive audience, and I wanted more stories, more mountains. I struggled to imagine the place with the details I had. I couldn’t get a clear image in my head of Idaho’s tallest peak towering above a disappearing river.

Other than the fact that my dad made the entire climb in cowboy boots and jeans, that’s all I ever discovered of his infamous 1984 expedition. I would imagine the cliffs and the chickens of Chicken-Out Ridge and the cold, dark rain clouds that had threatened climbers most of that Saturday. I would dream of my own body on that mountain, but in all of my childhood travels around the state, my family never drove past Borah. It loomed in my mind—the tallest mountain in Idaho, the one that took my dad and his friend to the edge of their abilities as hikers and leaders. It called my name.

When I was old enough to be a Boy Scout, my dad and Brent Hyatt were still the troop’s scoutmasters. Now they were seasoned and tested. They led me and my best friends on many adventures through Idaho’s Copper Basin, the Sawtooth Wilderness, the Frank Church Wilderness, and various other deserts, landscapes, lava tubes, and wild country.

Whenever we held planning meetings, these men would ask me and my fellow scouts, “Where do you want to go? What do you want to do?”

We always answered, “Mount Borah! Can we climb Mount Borah?”

The scoutmasters would always answer the same: “Not yet. We will save that one for later. Maybe when you’re a little older.”

One summer, we hiked fifty miles through the White Cloud Mountains. Another summer, we backpacked fifty miles through the Frank Church. On yet another summer adventure, we tramped fifty miles through the Sawtooth Range. Our troop was mostly neighborhood friends who all attended the same church, the same junior high, and the same high school. We did everything together.

We never climbed Borah Peak, though.

In 2000, after I had a couple of semesters at college, my dad called and said, “Can you come home for a visit in August? We’re climbing Borah.”

I went, of course. No questions. It felt like he was answering the request I had first made at age five. I had been waiting a long, long time for this climb. I invited my roommate Brady Wiggins and my girlfriend, now wife, Wendy Kammerman. We made arrangements with our various student jobs so that we could drive to Twin Falls to meet my family, and then to Borah Peak to climb it with my parents and my younger brother, Richard.

We camped out at the base of the mountain the night before our climb. The Northern Lights danced white behind the foothills of the Lost River Range. The coyotes woke us with their wild yips, and the Perseid Meteor Shower gave us a fantastic show. I hardly slept, but it hardly mattered. We left camp around four o’clock and spent seven hours laboring up that mountain. The trail in the year 2000 went more or less straight up Borah’s massif. It has since been rerouted for human legs, but I was twenty-one and hiking with my best friend and my girlfriend. I felt no pain.

I marveled as the cut-leaf mahogany forest made way for enormous pines, and then the enormous pines became twisted, gnarled, and isolated things on the edge of black rocks that eventually led to the yellow cliffs of Chicken-Out Ridge. Real images of real rock replaced childhood fantasies and misconceptions.

At the final cliff of Chicken-Out Ridge, I coached Brady, then Wendy, then my mother over the edge and down to the safety of Borah’s saddle, but my dad and my brother Richard stayed where they were. Richard was thirteen at the time, and he was all used up. He sat down to eat a sandwich and take a nap. My dad passed me a walkie-talkie, and I led our shrunken crew to the summit.

It was beautiful.

I have been back many times. I do not tire of the climb, the summit, or the views along the way (I mean I get tired, but I do not tire of these elements). I have even been back with Brady, who now lives in Idaho, and Wendy returned last year to climb with me and our youngest son, Finn, when he was eleven.

I have still never shared that summit with my dad.

In September of this year, I returned to the Lost River Range with Brady, and with David and Adam Christensen, my climbing partners of many adventures detailed in this magazine. We were there to tackle two more summits higher than twelve thousand feet: Donaldson and Church. We’ve slowly been checking off a list in our heads of each of Idaho’s twelve-thousand-foot mountains. These are the men I visit mountains with the most, and the Lost River Range gets more of my time than most others.

Whenever I visit, I text my dad, who now lives in Utah. I’ll text him a picture of, say, the Pioneer Mountains, small on the western horizon while I am high in the Losts.

“Where are you?” he always asks.

I wait for him to recognize the view because I cannot climb those mountains without thinking of him and the nearly twenty years I waited to climb in the Lost River Range with him.

“Idaho,” I text back, to stall, to tease the man who taught me to tease. Eventually, I finish the answer: “Lost River Range. New Mountain. Above Mackay. That’s the reservoir in the distance.”

“Oh, yes,” he replies. “Beautiful.”

And it is. It always is beautiful. Each new peak, each new climbing experience is beautiful. I can’t stop. I keep climbing mountains even though I strain my muscles and the limits of sleep. I climb and I return home late at night, or sometimes the next day, to tell my family about each new adventure.

Donaldson and Church share an approach that looks similar to many of the peaks in the Lost River Range. You exit Highway 93 and cross a barbwire fence onto a sagebrush plain cross-hatched with dirt roads and cattle paths. You wander the maze of two-track roads until you find one that points to the correct drainage. When the plain takes an angle too steep to drive, you park and camp.

Adam, Brady, Dave, and I camped under the cold stars of September after sharing drinks, candy, and stories. The coyotes, descendants of those that woke me twenty-four years ago, told us when to quit and go to bed. We slept until five, and then we headed up the trail to a dry creek bed that seasonally drains the mountains of their snow melt. Sagebrush gave way to mahogany, which gave way to pine. Pine didn’t last long, and soon we were walking on rock and alpine tundra while the music of an underground stream broke on rocks invisible to us.

The sun rose, and before us also rose Donaldson and Church. The peaks occupy opposite sides of the same glacial cirque, the crown of rock that once held a glacier—or perhaps better said, was formed by a glacier—that carved a series of basins. The lowest basin was nothing but loose rock, and our trail disappeared, so we began our crawl through those rocks. The next basin upheld a green puddle frozen on top, but a trickle of water from above wandered down beneath the ice. Bubbles and bulges formed beautiful shapes that Adam and I poked at with our trekking poles while we waited for Brady and Dave to catch us.

We sat near a four-foot high wall of solid rock and ate whatever meal came between granola bar and trail mix. We contemplated the basin above us: loose rocks scattered over solid rock and steep cliffs. Adam had traced a red line across a GPS compilation of images to give us a good map, but we also had to navigate the reality of which rocks looked firm and which looked most likely to cheat us and slide back down the mountain. We scrambled our way over the difficult terrain until it turned more steeply upward and became…even more difficult.

Two men from Pocatello caught up to us while we zigzagged through the layers of rock, but they refused to pass. They were moving more quickly but did not want the added challenge of finding the route. The going was tough, and we took our time, pausing to massage cramps, to eat, to shed a layer of clothing, and, often, to put that layer of clothing back on.

We reached the crest of the cirque before noon. Both peaks still looked far away, and Church looked absolutely treacherous. Since we had already agreed on topping Donaldson first, we turned that way and shortly found ourselves at the summit. A wooden sign proclaiming “Donald Mountain” greeted us, but we pulled a correctly labeled flag from an ammo can stashed in the rocks and took our pictures at the summit.

The Pocatello guys left quickly and headed for Mount Church. Our party sat longer than we should have and ate and ate and ate. I texted photos of the climb to my dad, and we hunkered in our coats, closed our eyes, and let the sun warm us a while on that cold, rocky mountain. From our perch, Church looked layered and loose. While the online trail guides all proclaimed that the ridge connecting the two peaks was an easy walk, the rocks proclaimed those guides were liars. Before long, the Pocatello guys turned around and headed back down the upper cliffs of the cirque. These facts and our exhaustion discouraged me, but I stood and headed down the peak of Donaldson to the connecting ridge. My friends followed close behind.

Walking the ridge to Church felt like a balancing act, sometimes on one side of the ridge, sometimes on the other. Sometimes a trail appeared in the loose rocks, sometimes it disappeared, and sometimes we walked on solid, black bedrock. Sometimes we scrambled on all fours and sometimes walked upright like men. The wind blew hard along the ridgeline. When the trail dipped below that line, the temperature soared. When we again walked along the mountain’s spine, we froze. There is no perfect way to climb a mountain other than to suffer the changing conditions with patience and slowly wind your way to the top.

The top tricked us (well, me) a couple of times. False summit after false summit played with my mind, and I sat down to eat while Adam took the lead. I was feeling terrible: tired, discouraged, and cold. Eating helped, and eventually all four of us sat on the summit and ate together. If you ever feel terrible in the mountains, you probably just need to eat.

From the summit we debated the identities of the peaks around us. To the north, Leatherman, Mount Idaho, Borah—maybe. To the east, Bell Mountain, Diamond Peak, the rest of the Lemhi Range. To the south, Breitenbach, Lost River Peak. And to the west, was that Castle Peak in the White Clouds? Was that Hyndman in the Pioneers? Not even our phones could help us too much, so we ate some more, and then we began the wandering path back down the way we had come.

We made it to the car around sunset. Pink light surrounded by orange suffused the mountains to the west. We shivered and worked our way out of our hiking shoes and sweaty jackets and into our flip-flops and puffer coats. We drove the maze of two-track back to the highway and were in Arco just before closing time to get a burger.

I got home before two that night, but it was close to two. The next day, my mom and dad called to ask me about the climb.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only

2 Responses to They Called My Name

Nathan Box -

at

What a great article! The detailed descriptions made me feel like I was hiking right along with Michael and crew. He captures the majestic beauty of the Idaho mountains perfectly! I cannot wait for the next adventure.

Ethan Wydick -

at

I’ll never forget when you and Eckersell were the leader of our scout troop and we hiked up jackass pass. Reading your article put that at the front of my mind and I’ll never forget it. It was one of my most memorable times. I hope to hike Borah someday and have a tale to tell.