No products in the cart.

Top of the Hill

Racing the Ghosts on the Corners

By Kitty Delorey Fleischman

There’s just something about cars and speed. It’s always been part of my psyche. I liked it when Dad drove, because he’d pass other cars.

Mom almost never passed anyone—even on two-lane roads before the days of Interstates. When Dad would pass, she’d draw in her breath and say, “Oh, Don,” and gently touch his forearm. I never saw Dad do anything unsafe or impatient, so I had no qualms when he was at the wheel.

My own fascination with driving fast started in drivers’ ed in 1964 when Mr. Heim, our instructor, would allow me to drive only in second gear the entire time, telling me I had a lead foot. My daughter called me a lead-foot too, although I rarely had cars with enough power to challenge the speed limits, and many of my roads were dirt or gravel, which didn’t lend themselves to much speed.

All of that changed around 1988 after I’d been diagnosed with polycythemia vera, a chronic leukemia that was considered incurable. Apparently I’d had it for some time when it was caught before a blood donation. Looking at the sample under the microscope, the nurse said, “It looks funny.” That simple statement led to months of tests through my family doc and specialists, who tried to find out why it looked funny. Chasing up a lot of dead ends, they finally figured it out, and I was the first patient with polycythemia vera diagnosed in Idaho. For several years, it was treated with phlebotomies, where blood is drawn off to remove the extra cells, then is discarded. (One of the nurses gave me a wink and told me it had her roses thriving.) As the blood was drawn off, however, my marrow decided I needed yet more red blood cells and started making them even faster. By the time my blood looked like bad motor oil, thick and gunky, my doctor wanted to give me chemo, adding that an extremely high dosage was required, which wouldn’t cure it, but would slow down the progression of the disease—once. I refused, preferring quality of life over quantity. (Interestingly, later research suggested that the disease does not mutate to acute leukemia, but that chemotherapy may cause the mutation.)

Life went along for more than a year with the doctor telling me that he didn’t know how long I had left, but if there were things I wanted to do, to do them now, as he could guarantee I’d never see fifty.

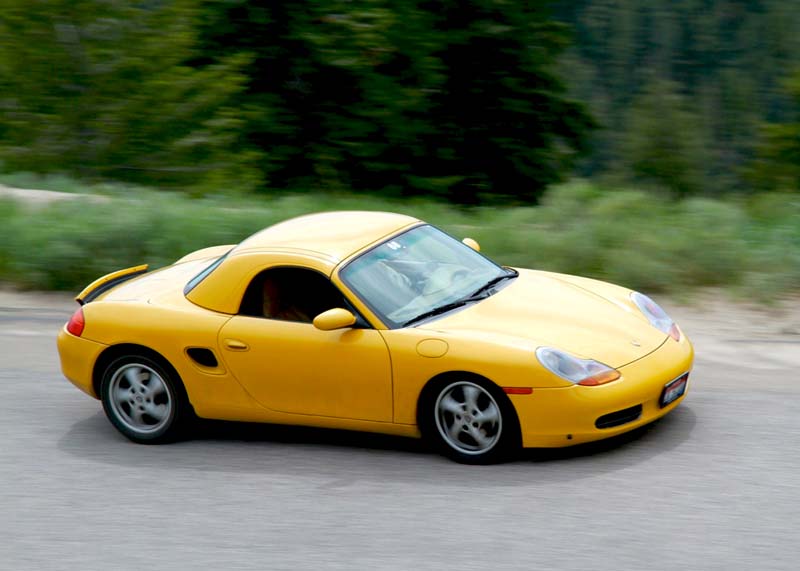

The author driving Bogus Basin's Sky Corner. Dana Jacobsen photo.

BLU MAX wrecked, 2002. Kitty Fleischman photo.

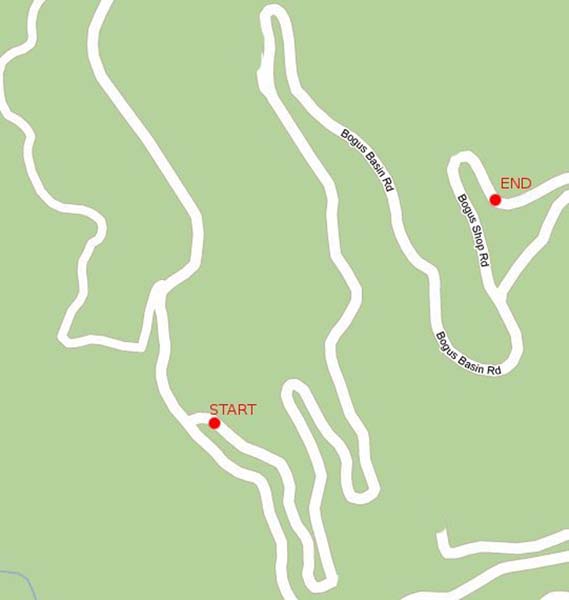

The race map. Courtesy Bogus Basin Bacchanalia.

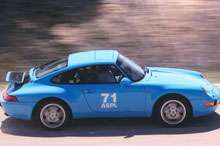

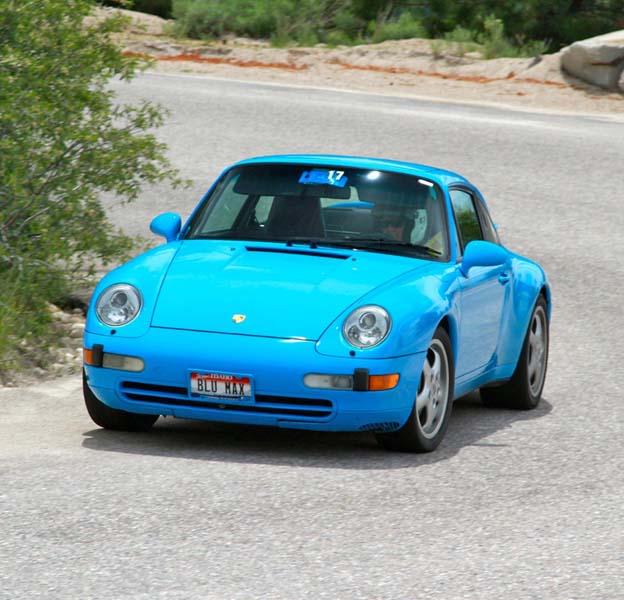

A racer on the course. Gary Gelson photo.

Gerry Fleischman, the author's husband, steps on the gas. Gary Gelson photo.

Kitty Fleischman in the 2016 race. Gary Gelson photo.

Sunrise near Bogus Basin. Knowles Gallery photo.

One day as Gerry and I were going for an anniversary lunch, we saw a little red ‘67 Porsche on the corner of 27th and Main in Boise with a “For Sale” sign on the windshield. “Mark it SOLD!” Gerry didn’t quite share my enthusiasm, but it was exactly what I never knew I wanted, yet did. Whatever I was thinking, somehow we were able to spread the cost over three credit cards, and it was mine.

A friend owned an auto accessories shop, and he suggested I go up to watch the Bogus Basin Bacchanalia (BBB), an annual event when the Silver Sage Porsche Club runs the hill at Bogus Basin. I didn’t really want to go, but he talked us into it. Sitting in our lawn chairs in a corner of the parking lot, I knew it was exactly what I wanted to do.

Gerry said I couldn’t do a hillclimb unless I learned to autocross, and I definitely didn’t want to do that. Those are the races with a bazillion cones in a parking lot, and you have to find your way through the cones to the finish line. But I did want to do the hillclimb, so I determined to do it.

After I refused the chemo, Beverly Mountain, who raced with us in the Porsche Club, told me about seeing an article in Family Circle magazine about someone who researched clinical studies on various cancers. That lead took me to a clinical study at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle using interferon, and I became part of that study. Within weeks, polycythemia vera started to seem like more of an annoyance than a death sentence. But the medication turned my brain into Swiss cheese, and I didn’t know how I could ever find my way through the cones. Eventually I did decide to do it, testing the patience of everyone, and my first autocross was at Sun Valley. I was being coached by Henry Watts, who wrote the book, Solo Racing. We both thought my little twenty-five-year-old car was pretty special, and I came in third place against an astonished group of veteran drivers from Salt Lake City.

But the interferon treatments began to feel brutal. Injections with the E. coli witches’ brew three times weekly were taking their toll. Some days I felt lost in a fog, although I got through the summer promising myself little rewards along the way: an autocross, a swim at Idaho City, a movie pick, a nap on Saturdays, a ride on a sunny Sunday afternoon.

I raced as often as possible, surprising myself as I flew through the cones, looking to get faster with each run. I always did well. To someone standing back and watching, it may not look like the cars are going very fast, but when you start going around 90-degree, or sharper, corners at 35 mph, it feels like you’re whipping along at top speed. My little red car was dubbed Lillian Redrocket Fleischman, and we had a number of great races together.

Meanwhile, my blood counts went back down to normal and I adjusted to life on interferon. The disease went into remission and never came back. Twenty-plus years later, interferon is the preferred treatment for it.

The first time I drove Bogus Basin was 1993, a few years after being diagnosed with “incurable” leukemia. I set a new Porsche record for my class on the hill, and was over the moon. My dad had flown out from Michigan to be there, and he’d spent the pre-race hours begging me not to do the race. Once I’d done the first run and had the new record, Dad was more at ease, and he jumped up and down cheering at the top of the hill as I drove up.

We’ve done a lot of autocrosses since that first one in 1993, and I’ve done a lot of hillclimbs along the way. In 1996 I had a chance to get my dream car, a Riviera Blue Porsche 993 (“swimming pool blue” is the easiest way to describe it) that I call BLU MAX.

Weeks after the Boise Parade in 2002, BLU MAX and I were T-boned at the corner of 10th and Jefferson by a kid running a red light at high speed in a car that belonged to a “friend of a friend.” We were spun backward, knocked across three lanes, and ended up thirty feet beyond the intersection. It was fortunate his car couldn’t be moved, because he had tried to flee the scene. My heart was breaking, but BLU MAX and I kept driving together until an ongoing parade of heart problems took me off the hill in 2006.

In September 2013, I had a crushed vertebrae and was paralyzed for about eight days before the doctors decided to do surgery. For more than a year, I couldn’t even operate the clutch. In October 2014, I had a heart attack, and in October 2015, I had open-heart surgery to replace the bad aortic valve. BLU MAX and I had both been through a lot, and I thought our racing days were finished. But I completed cardio rehabilitation this spring and was feeling great again, except for gout that attacked my feet and won’t seem to go away. The cardio therapy team told me I had another good ten years. What kind of years would they be without racing? Reading about the upcoming Bogus Basin Bacchanalia, I began to get the urge to drive again, and Gerry, as he always does, backed me up.

Bogus in 2016 marked my thirtieth race at the hill, but it was the first time since 2006. Ten years is a lot of rust to overcome. I needed help to get into my five-point harnesses—although I was so slow, I probably didn’t even need them. Gerry had bought the five-point belts for me for the Teton Hillclimb in 1998 when I’d gotten to where I couldn’t snap the regular inertia seat belt tight enough to hold on corners, and I loved them. With the belts snugging me into the seat, I was Queen of the Hill at the Teton Hillclimb that year.

At BBB this year, a slender, handsome young man walked up to me, stretched out his hand, and introduced himself. As a sixty-eight-year-old great-grandmother, that in itself was a thrill, but then he said, “It’s great to see you here. When I was a little kid, I used to come up here to watch the race, and I loved to watch you race in BLU MAX. Then for years you weren’t here, and I was disappointed. I’m so glad you’re back. This is like the return of a legend.” It really doesn’t get any better than that.

My first few runs were extremely shaky, and I could hear my little racing teddy bear laughing at me and taunting me from the back seat. I couldn’t have that, so I got on it a little harder with each run. As I sat at the bottom of the hill, waiting for my signal to go, I again felt the same old excitement.

The signal comes, I dump the clutch, and I’m off. Corner 1, Deer Point, is a simple hairpin. Corner 2, the Wall, is an inside corner with a wall of rock on the outside of the turn. Here you’ll want to stay a little bit away from the fastest route and give yourself some slack. Corner 3, Horseshoe, is another simple hairpin, and you’re off for Corner 4, the Esses. Corner 4 is probably the most deceptive one on the course. It looks like nothing, but you can get your car sashaying back and forth until you’re in a spin. I’ve done it. So have lots of others, and it happens before you know it’s coming.

Corner 5, Sky Corner, might be the most visually intimidating, but it’s not that hard to drive. It’s the longest straightaway on the course, so you’re carrying the most speed into the corner and as you go up to it, all you see is sky. You have to trust that the road is still there. It’s steep getting out, so you downshift and are off for Corner 6, The Rocks, another tricky one. If the road was about a foot wider, you could almost go straight through. But it isn’t, and you’d better give it due respect. More than one car has gone off that edge or crashed into the rocks for which the corner is named. Corner 7 is Silver Queen, a decreasing-radius corner that gets tighter as you go into it. With a rear-engine Porsche, you can’t lift in the corner. If you go in too fast, you just keep your foot in it and keep going.

As I was starting to get fast, I once went into Corner 7 with too much speed and found myself drifting toward the edge. I kept telling myself out loud, “Don’t let up . . . don’t let up . . . don’t let up,” as every fiber of my being wanted to let up and hit the brakes. I kept my foot in it, though, and didn’t let up, brought it back on the right line, and took it around Corner 8, Caretaker Corner. Woo-hooo!

My final time in 2016 was sixteen seconds slower than my best-ever time, but I was happy to have improved by almost eight seconds over the course of the day. And it was quick enough to bring home the Queen of the Hill trophy for the fastest women’s time.

I’ll be out autocrossing again this year, and if I can, I’ll be back for 2017—despite the ghosts on the corners. Over the years, I spun out once in Corner 4 and once almost went off the edge at Corner 7.

Thanks to everyone who helped me get sticky tires this year at the eleventh hour, thanks for all of the kindness and encouragement from everybody on the hill. Thanks especially to Gerry for letting me know he still believed in me to get to the top and, as always, for making me laugh. When I was grousing about my times, he pointed out that I was the only one on the hill with racing numbers AND a handicap placard on my car.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only