No products in the cart.

Unflippable or Unflappable?

Rafting and Climbing in the Salmon River Canyon

By Ray Brooks

Long ago, I heard there were two types of whitewater rafters: those who have flipped their raft, and those who are going to flip their raft.

Despite about four hundred days of whitewater rafting over forty-one years, mostly in Idaho but also on other rivers in the West, including the Colorado through the Grand Canyon. I somehow had never, ever managed to flip my raft, even though I had witnessed flips right in front of me. I had started to worry that I might never have the enjoyment of flipping my raft and, of course, at age sixty-five, new experiences were hard to come by.

My wife Dorita and I had chosen a gorgeous August weekend to raft with friends on the Salmon River, upstream of Riggins, just before Labor Day 2013. The plan was to raft above and below a riverside car camp, using light and maneuverable rafts. We would leave our camping gear and one vehicle at a beach campsite, then drive our rafts upstream about fifteen miles. After launching the boats, we would raft down to the camping spot and repeat the process the next day, for the end of our adventure.

We took our small “sports car” raft, which we call the Toy Boat. We lent our friends, Jerry and Angie Richardson, our much larger, “unflippable” Cataraft, because while rowing the Toy Boat a month earlier, Jerry hadn’t seen a rock hidden within a minor rapid on the Snake River near Hagerman. The Toy Boat touched the rock, tilted ninety degrees and emptied, tossing Jerry, Angie, and Dorita into the river. Then it continued on alone, proud and upright. I was nearby in a kayak and rescued Dorita, while Jerry and Angie swam to the Toy Boat and once again took command of it.

On our Salmon River trip, our friend Mark Mason, who spends nearly as much time river running as guides do, came along for leadership with his Super-Puma, a slightly longer, wider, and more stable version of our Toy Boat. The way he rigs it, with two heavy coolers in the boat, makes it a bit slower than it otherwise would be, but much more stable.

After launching our boats late in the morning and enjoying some mild rapids, we sighted a black bear yearling, and it was pretty cute. At first it moved away from us, then it hiked after us for about a quarter-mile, and then jumped in the water and started swimming strongly towards us. We didn’t really believe it was chasing us, but we all rowed fairly hard for a while, until we saw it climb onto the opposite bank.

Mule deer buck at riverside. Dorita Hoff photo.

Ray and Dorita toast his survival after his first-ever flip. Jerry Richardson photo.

The climbing route Mark named "That Crack on the Salmon." Ray Brooks photo.

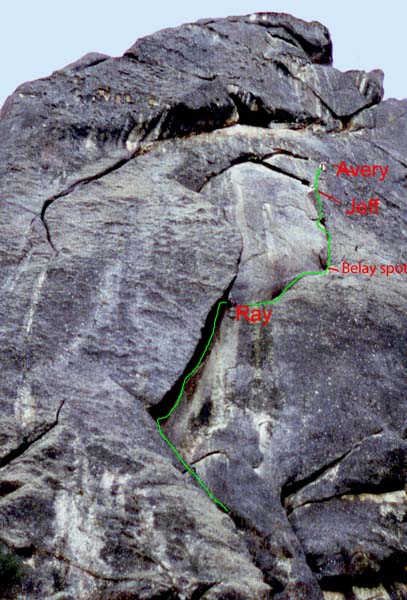

The "Dream of the White Sheep" climb. Courtesy of Ray Brooks.

Ray and Dorita in the "Toy Boat" on the Salmon River. Jerry Richardson photo.

Mark in his highly maneuverable yet stable raft. Dorita Hoff photo.

Jerry and Angie in an "unflippable" raft borrowed from the author. Dorita Hoff photo.

The bear that followed the rafters. Dorita Hoff photo.

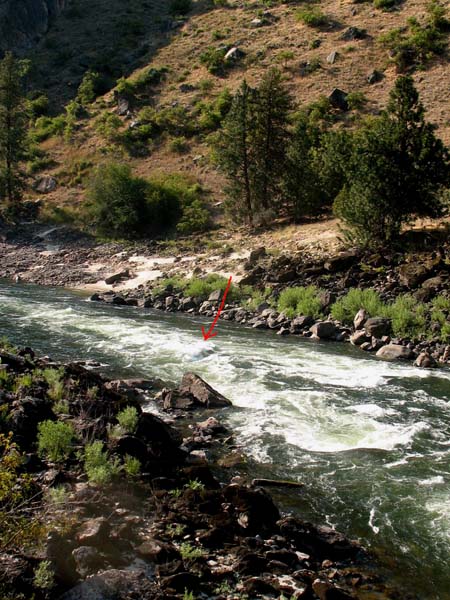

The rapid that flipped the boat. Ray Brooks photo.

Relieved that the bear no longer seemed to be pursuing us, we relaxed a bit, and soon arrived at an un-named minor rapid just above Manning Bridge. Looking downstream, I saw waves standing in the center of a rapid that dropped steeply and would likely offer a fun ride, if we avoided the large holes on both sides of it.

Mark, who was leading, avoided the final large wave in the middle, but I didn’t profit by this example. The flip-wave looked to me just like a fun standing wave, but it had some real hydraulics going on when we hit it. Our boat stopped, and then tossed us sideways and over. It was the best possible type of flip: Dorita and I were both tossed well clear of the raft before it went all the way over, plus the water was deep and warm, and we were at the last big wave in the rapid.

However, we still had some fast water and a couple of large rocks to avoid. With a surge of adrenaline stimulated by our unexpected bath, we fought our way through the strong current back to the Toy Boat. Using our whitewater survival tactics, we tried to stay on its upstream side to avoid the risk of being trapped between it and any rocks it careened off. That worked briefly until the boat pivoted, just before it smashed into a large rock, forcing us to let go. By then the water had slowed considerably and our two other boats were able to reach us. We were soon upright and on our way.

After drifting under Manning Bridge, which was constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s and is now finally being replaced with a new bridge, we had slow water for more than a mile. We floated by impressive granite buttresses, on which Mark and I had done adventure climbing routes in the late-1970s and early 1980s. Since our fellow rafters also had climbing experience, they made appropriate sounds of admiration while Mark and I pointed out long and difficult routes we had ascended, including our favorite, which Mark called, “That Crack on the Salmon.” It has nine 150-foot leads, and you do some walking in between the upper leads. It was not just a climbing route but an adventure, as the name of one of the upper leads attests: the “Chimney of Horrors.” A description of it in my 1980 climbing journal reads: “Highly recommended as an unusual problem! This lead features jamming on huge flakes inside a wide and scenic chimney.”

In March and April of the early 1980s, we used to drive 165 miles from Moscow and Pullman, often bringing along students from the University of Idaho and Washington State University, for warm spring days of trying potential new routes. Adding to the adventure were poison ivy, rattlers, river views, uncrowded sandy beaches, and huge loose flakes of granite. What’s not to like?

Since then, the area has fallen out of favor with rock climbers. I was somewhat amazed to see that little climbing activity showed up on the Internet under searches for the Salmon River, Idaho, or Riggins. One website (www.drtopo.com/submitted/riggins.pdf) mentions the area of our adventure, the Salmon River Crags, but it has no details on routes. “These crags are located alongside the Salmon River about 14 or 15 miles to the east of Riggins,” it says. “The obvious granite outcrops tower above the north side of the road just before the second bridge (Manning Bridge). There are more than thirty established routes here, many of which have multiple pitches. There are crack climbs, bolted face climbs, and mixed lines. Some of these routes have healthy run-outs that require a cool head and a change of underwear. The difficulty ranges from 5.8 to 5.12.”

One of the biggest buttresses had an obvious line up it, which started with a very wide chimney, which is a crack big enough to fit your body into. The route got steeper and narrower, and soon turned into a difficult off-width crack, which is too wide to jam hands or feet into, but too narrow to fit your body into. Back in 1980, after retreating from the chimney on my first try at the route, I was able to lure a very good climber friend, a then-WSU student named Avery Tichner (my secret weapon), deep into Idaho to deal with this challenge. A group of us drove down from Moscow-Pullman on a May weekend that year.

Avery had brought a new climbing disciple with him, a pleasant lad named Jeff, and the three of us threaded our way up through brush and poison ivy to a spot I had dubbed “White Sheep Buttress.” I called the route itself “Dream of White Sheep,” a takeoff on a famed British sea-cliff route named, “Dream of White Horses.”

I did an easy lead up to the difficult chimney. Avery led the chimney and off-width climbs cleanly, although grunting and panting a little at the end. He pronounced it a 5.10d in difficulty, and set a two-bolt belay anchor at the top of it. After following his lead with tight ropes and some grunting of our own, we walked a three foot-wide ledge about forty feet, up and over to the crack that was the obvious start of the third lead. From a comfy belay spot, that lead went up a slab with a lie-back crack, which you climb by leaning backward and to one side with your arms straight and feet shuffling up the wall. I had been last man up and was out of breath, so I told Avery to keep leading.

On his lead, Avery stopped about sixty feet above us and drew our attention to a loose flake he was avoiding. The flake looked like a car door made of granite, and was clearly balanced precariously, just left of the lie-back crack that Avery was hanging onto. He suggested that the next man up might want to kick the flake off, and then continued up.

Jeff was going next. I strongly discouraged him from even touching the loose flake, since it was poised directly above our belay. After Avery finished the lead, and the Jeff started up, I had an epiphany: I was going to die, if I didn’t move! I unclipped from the belay but stayed attached to it with my rope, and walked the ledge forty feet back down to the belay anchors at the top of the chimney. I clipped into the bolts, hung my pack in front of me so that it covered my chest and abdomen—and waited for something bad to happen.

I was not disappointed.

Jeff touched the loose flake while he was going by. It broke free and slid sixty feet down the steep slab to the exact spot where I had been standing minutes before. When the flake, which I’d say weighed three hundred to five hundred pounds, hit the belay spot, it exploded with a boom and a cloud of rock flour. Small pieces of the flake bounced off the pack that was protecting me, and a saucer-sized piece rolled down the ledge, delivering a bone bruise to my right ankle. The rest roared off the buttress and into the gully below.

I was impressed by the amount of rock that the exploding flake picked up as it went down the steep gully. Five hundred feet below me, a gravel road ran alongside the Salmon River, and as I watched the rocks tumble toward the road, a motorcycle rider came into view. He did a quick 180-degree turn and fled, as rockfall roared across the road and splashed into the river.

I yelled up that I was OK, and limped up to the destroyed belay spot. The rope from Jeff to me was nearly chopped through by the flake. Avery wanted to continue but I shouted that I wasn’t following with a damaged rope and a bum ankle.

We retreated.

A few weeks later, Avery went back without me, finished the route, and rated it somewhere in the 5.11 range, which then was in the advanced category of roped climbing. None of the various routes above the Salmon River that we climbed were ever published in climbing guidebooks or magazines.

On the river, as we floated beyond the site of my climbing adventure, we were a little nervous about other small rapids between Manning Bridge and our camp, but all went well. We were even rewarded with a good look at a mule deer buck on the riverside, its antlers still in velvet.

At our riverside camp that evening, of course, we had a survivor’s party.

Our next day on the mighty Salmon didn’t provide more flip excitement, but we did enjoy several challenging rapids, and I picked the easiest route of descent through the largest rapid at Lake Creek. Jerry and Angie followed my “chicken-shot” line, while Mark picked a more interesting route down the middle.

By early afternoon, upstream winds were gusting in the 20 mph to 30 mph range through the Salmon River Canyon. Rather than fighting the winds, we went with Plan B and took out at Short’s Bar above Riggins.

I confess to relief at not having to run a stretch below Riggins rapids in the Toy Boat in winds that strong. It’s always fun to do something new at my age, but it also depends on what that something is.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only