No products in the cart.

Walk the Walk

An Ancestor’s Journey Retraced

By Melissa Lee Kinsey

We were walking on Fir Grove Road, somewhere between Fairfield and the Little City of Rocks north of Gooding, when a truck bounced toward us. We had walked about six miles on this dirt road that parallels Highway 46 and all we’d seen were sagebrush, lava rocks, and the shadows of small rodents that scurried to the side of the road as we approached. So we were excited by the truck and wondered who was behind the wheel.

A young man brought the truck to a stop, leaned out his window, and grinned. “Just out for a stroll here?”

It was a pretty casual greeting for the circumstances. We learned he was working Fir Grove Ranch and was driving to check on the cattle, as he did every day. Given the remote location, I can’t imagine he saw people very often, especially a group wearing cushioned running shoes and compression socks and carrying walking sticks. He must have been shocked by the sight of us four: two of my brothers, my husband, and me. He may have thought we were lost, or nuts.

My oldest brother, Dann, introduced our group and said our dad’s family was from the area—our grandparents had owned a ranch nearby. We were walking this route to commemorate the trek our grandpa, Hyrum Dixon Lee, had taken to get to the hospital in Gooding for the birth of our dad. It had been an impressive journey through the night and over deep snow in February, 1936, driven by doctor’s orders that he get to the hospital, whatever it took.

His wife, who was forty and had lost a baby some years earlier, was due anytime. The roads were closed because of a recent blizzard, so he rode his horse to the train station seven miles north, patted Ol’ King on the rump to send him home, and then found that the train was not running. He walked back to the ranch, ate dinner, readied a pair of skis, and headed south towards Gooding. Some thirty miles later, he arrived in time for the birth of our dad, Del Ray Lee.

“Where’re y’all from?” the young guy asked.

My brother told him: Birmingham, Alabama; Memphis, Tennessee; and Chicago, Illinois.

“Y’all are from some pretty lousy places,” he said in a friendly tone. I think he felt sorry for us. It made me think of our dad’s family, who had wondered how he could have left Idaho, trading his home patch with its rugged beauty and open spaces for a suburban home in Orange County, California, where he and our mom raised us.

I’ll tell you how. After high school he wanted an education but didn’t know what he wanted to study, so he joined the Marines. Not far into his tenure he met our mom. End of story. It was love and a growing family that he left for. They did return to Idaho, where he earned a degree in electrical engineering at the University of Idaho in Moscow. But then they moved back to Southern California, where the jobs—and her family—were.

He tried to give us the same freedom and love of the outdoors that he had growing up. He took us fishing and camping and back to Idaho for a week each summer. I’m sure he wished he could have done more but when he was twenty-four he started having symptoms from what was eventually diagnosed as multiple sclerosis. He died at thirty-nine, when my brothers and I ranged in age from eleven to seventeen. One of the many things we lost through that early death was the chance to have an adult relationship with him.

The walk was what Alfred Hitchcock would call a MacGuffin: something concrete to focus our trip on while the real action happened, which in our case was learning more about his family, his upbringing, and things we may have wanted to ask him as adults. We had coordinated with our cousins, the children of our dad’s brother Dal, who offered to help us with all that.

This was more than our rancher friend needed to know, so we asked about rattlesnakes, which we’d been warned grew to “Boone and Crockett size” out here. We were lucky, he added: it had been cold this morning so we had avoided that danger. He inquired about our destination, which was the turnoff to Little City of Rocks from Highway 46, another six miles on, and he wished us a good walk.

The family members at Flattop Butte. Dann Lee.

Dann and Robin on Camas Prairie. Dann Lee.

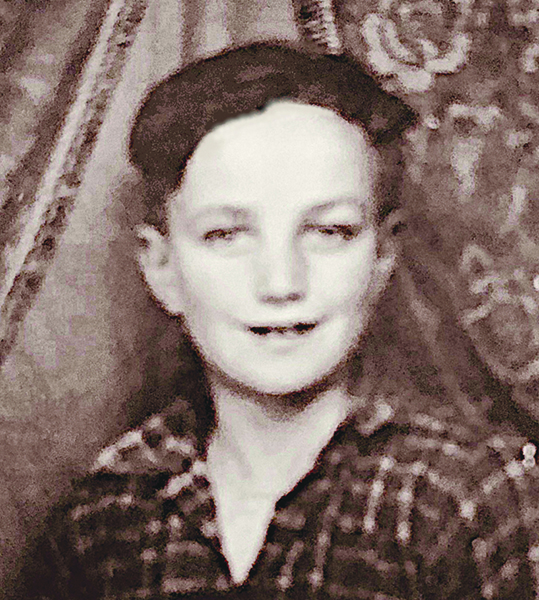

The youthful Del Ray Lee. Courtesy the Lee Family.

Florence and Hyrum Lee. Courtesy the Lee Family.

Grandma Lee Young. Courtesy the Lee Family.

Grandpa Lee and his brothers. Courtesy the Lee Family.

Camas Prairie. Pam Jones.

Another view of the prairie. Pam Jones.

Rounding the bend near Flattop Butte. Dann Lee.

View of Mormon Reservoir from Fir Grove Road. Dann Lee.

Grandpa Lee with his horse. Courtesy the Lee Family.

*****

That morning we had started close to the ranch where our dad grew up and where Grandpa Lee had begun his trek. The previous day, two of the cousins who had been helping us on our journey, Terry and Jeff Lee, had taken us to visit the ranch as part of a tour of the area, which included the route we would be taking. When we visited Idaho as kids, we had stayed in Gooding near a ranch our grandparents owned there. We had mistakenly thought that was where our dad grew up, so the ranch here on the Camas Prairie was new to us.

In the months leading up to the trip, Terry had shared some of his writing about life on the prairie and from one of his stories we had learned of Grandpa Lee’s trek [see sidebar, “Del Ray Lee Is Born”]. He and his sister Pam, who is the keeper of the Lee family records, went out of their way to help us learn more about our dad. They even reached out to friends and relatives who had known him and who provided firsthand stories of growing up with him. Much of the information in this story is a result of that collaboration with Terry and Pam.

Grandpa Lee ran cattle on this ranch, starting with a few head and eventually expanding to three hundred head of registered white-faced Herefords. He was well-respected, always willing to help a neighbor. He and another rancher worked hard to establish the Black Canyon Cattlemen’s Association, which gave ranchers in the area exclusive grazing rights north of Gooding.

He also was renowned for his career as a big-game hunting guide. For years he had guided throughout the Soldier Mountains and in the Selway–Bitterroot Wilderness. According to family lore, one of his clients was Bing Crosby. Later he guided in Alaska and then came home with prize trophies and stories of adventure. His business card for guiding in Alaska bills him as “Grizzly Bear Lee,” a nickname he got for seeming to be a magnet for grizzlies.

Dann asked for details of a story we had heard that Grandpa had been guiding in the Selway when our dad died. Helicopters were restricted in the area so that they could not be used to track animals. Someone in the family got hold of Senator Frank Church, who gave permission for a helicopter to pick up Hyrum that day, which allowed him to make it to the funeral. Dann asked Pam how it was that our grandpa knew Frank Church and, without missing a beat, Pam said in our family the question was, “How did Frank Church know our grandpa?”

We had always had pride in our Idaho roots. To learn more about our dad and his family only deepened that pride.

*****

After our interaction with the young rancher we came upon Fir Grove Ranch, the only house on our route. Our cousins had told us that the route we were on was the same one they used back in the day to help Grandpa drive his cattle south to Gooding. They overnighted here on those cattle drives.

When Grandpa was six in 1900, he came to Idaho with his parents from Freedom, Wyoming. In later years he recounted how a few families settled the area, each acquiring fifty or so head of cattle. Everyone was expected to help in the chores, including the making of milk and cheese. He said he spent so much time milking cows that he tried to conjure a way to attach the stool to his backside so he wouldn’t have to tote it from cow to cow.

Our Grandma’s family settled in this area, too. They left Teasdale, Utah, in 1902 or 1903 with two other families, traveling in covered wagons and by train for part of the way. In a roundabout manner they ended up on Camas Prairie, where they camped on their first night under a big willow. When a brother fell ill with spotted fever, they told the other families to move ahead without them, and said they would catch up. By the time Grandma’s brother recovered, though, the rest of the children had come down with mumps. Even while our great-grandmother cared for her family, she pulled out her sewing machine and made clothes to sell to settlers in the area.

Once the children were healthy again, the family continued north to Soldier Creek, where they lived for a few years before returning to the Fir Grove area to settle.

The families of our grandparents were part of a group of families mostly associated with the LDS Church who talked of how, if they could gain access to a water supply, they would be able to farm the Camas Valley. They collaborated on setting up camp while they built the dam that created what is now known as Mormon Reservoir.

Eventually, the group decided to move their settlement north of Camas Creek. They built a schoolhouse and church and other buildings there, calling the settlement “Manard,” which is derived from a German surname that translates as “strong” or “hardy.” On our tour the previous day, Terry and Jeff pointed out where the settlement had been located near a grove of trees. The buildings had been moved and none remained. What used to be the schoolhouse is now a city building in Fairfield.

Despite the hard work of the pioneers, they found it was difficult to forge a living on the prairie. Even with water from the reservoir, Terry said, it was a hard-fought battle to grow the crops needed to sustain the livestock and the families. Grasshoppers and gigantic Mormon crickets threatened the crops and droughts had to be contended with. Bigger farms swallowed up smaller farms and schools were consolidated as people left for employment in nearby towns or wherever they could find it. Some moved to nearby Fairfield or south to Gooding where the weather is milder and the growing season longer. No doubt some left the region altogether, perhaps for jobs or warmer climates.

I had read about pioneers in textbooks but having a family connection to these stories changed how I took it in. I now find what they did to be absolutely amazing: how hard they worked to build their community, the dangers they faced, and the courage and stamina with which they moved forward. I’m struck, too, by how the community worked together, sharing in the chores and combining their skills and manpower to build a dam and a settlement.

Our dad had a wonderful appreciation of community. He and our mom were at the center of many groups, active in our Little League, our schools, our church, our neighborhood. Dad was well-liked and respected and we felt the importance of it everywhere we went. The lessons he had learned growing up in Manard, where everyone contributed and all were supported, permeated our childhood and stay with us today.

*****

A couple of miles past Fir Grove Ranch, the going got tougher. It had become quite a bit warmer and the distance was taking its toll. Our online examination of the route had made us think it was all downhill. In real life, there seemed to be hill after hill and, especially near the end, a steep one.

About a mile from the finish I got a cramp in my foot and left the group to hurry ahead, eager to get out of my high-top shoes. As I rounded the last bend in the road, I saw the van my brother Scott had rented. Wisely, Scott had volunteered right away to drive the support vehicle. His wife Diane was with him. She raised her hands in victory, shouted, “You did it!” and ushered me into the van. As soon as I got my shoes off, the cramp was alleviated and I felt a little foolish and humbled. I liked to imagine I was tougher than that but, in this case at least, I had not lived up to my pioneer roots.

When the rest of the group arrived, we gathered outside the van to celebrate. The walk felt like an achievement and certainly gave us an appreciation of Grandpa’s much longer journey—without the benefits of cushioned shoes, compression socks, and a support vehicle. What he did have, which we didn’t, was a lifetime of hard manual labor. He didn’t have to train for an endurance event. His daily life was enough.

We especially celebrated the connections we had made with the cousins who had been so helpful in planning the trip, researching our family history, learning more about our dad, and answering our questions: Terry and Jeff Lee; their sisters Norma Hutcheson and Pam Jones; and a cousin of our dad’s, Kenny Lee. This was an unexpected and wonderful bonus.

*****

One of the best parts of the trip was simply the time we spent together in a place that held much meaning for us. We rented a home in the Silver Creek area east of Fairfield, a beautiful place where we were visited by a moose and her calf each day and where the creek that ran through it into the foothills in the distance felt good and right for our journey.

One night, my sisters-in-law and I sat around the dining room table and talked as our spouses watched a football game in the next room. The other women knew my story but that night they each shared something of their own personal histories. It was

an evening of genuine, open conversation that illuminated much of what I’d been thinking about, but from a different direction. It created one of those moments of clarity that stands out as special and enduring.

They talked about childhood events and adults who were important to them and as I listened, I realized we all have a story to tell, because what happens to us in childhood is carried with us throughout our lives, informing every phase, every relationship. I was struck by how each of our internal lives is deep and complicated in ways that sometimes only our siblings— those who lived it with us—can understand.

Del Lee Ray Is Born

By Terry Lee

As my Aunt Ilene lay in a hospital bed in a Twin Falls nursing home toward the end of her life, she recounted many stories from our family history. I wrote down this one to capture my Grandpa Hyrum Lee’s thirty-seven-mile trek through a stretch of southern Idaho to attend the birth of his son, my uncle, Del Ray Lee. Recently we found evidence that Grandpa had skied at least part of the way, but what follows is the story as I originally heard it.

The haggard man made his way up the steps, hoping he had not missed what he had worked so hard to achieve. He had lost track of time and the winter darkness had come early and stayed late. The winter of 1936 had been harsh. Above-average snowfall made it worse for the occupants of southern Idaho’s Camas Prairie and everyone could have done without the relentless winds that had piled the winter white into impassable drifts.

He had ridden his horse seven miles from his homestead to Fairfield intending to hop the next train headed south to Shoshone and shorten his journey to Gooding, which would have the added the benefit of getting him out of the cold. In Fairfield, he put the reins over the saddle horn and with a swat on the rump sent his steed homeward. Unbeknownst to him, the train had not had a scheduled arrival in thirteen days. He was left to his devices with only the clothes on his back.

He made contact with two men from Gooding and arranged to meet them at Flattop Butte north of Gooding, which was far as the roads had been plowed. With grit and determination, he lowered his head into the gusts of wind and put one foot in front of the other. My Aunt Ilene said as my grandfather plodded along, he thought about the life he lived and the hardships he had known but would not trade with any man. Complaining and self-pity had taken up no residency in this man’s life.

Born in Wyoming in 1894, he came to the prairie as a small boy in a lumbering Prairie Schooner, walking more often than not to let his mother and sisters ride. Each spring, he and his siblings often stared in awe at tribal people who still made the trip to the prairie to gather the bulbs of the camas plant, its tops covered with all shades of purple flowers.

He was number three in a family of thirteen siblings, two of whom had died at birth. Early in my grandfather’s life, fate took his father away and made him “the man” of the house. He was the eldest son, which meant he grew into manhood at too early an age, having to care for his mother and siblings. He learned many things from attentive watching, such as driving teams that hauled freight and the stagecoach that headed through the south hills to Gooding, just as his father had done. I think it’s more than likely that these endeavors molded what could be called an internal compass—the knack of knowing where you are and where to go.

In all likelihood it was this compass that led him towards the rendezvous with his friends, who would bring him to the hospital in Gooding. But when he got to Flattop Butte, it was apparent there would be no ride the rest of the way. He later found out that his friends had gone on a bender and reneged on their promise. My grandfather looked south toward the lights and according to my Aunt Ilene, it seemed as if his feet had a mind of their own as the cadence began again of “one in front of the other.”

When he finally arrived and opened the front doors of the hospital, he thought he could hear the wailing of what he had ventured so arduously to see. The staff pointed the way and he strode into the room, the rolled cuffs of his Levis filled with snow, and looked upon his wife and their newborn son. Together, they named him Del Ray.

He soon walked to the house that he kept in Gooding and slept the sleep of exhaustion through all the daylight hours.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only