No products in the cart.

Water Everywhere

Fertile Farmland Drilled Full of Holes

Story and Photos by Mike Cothern

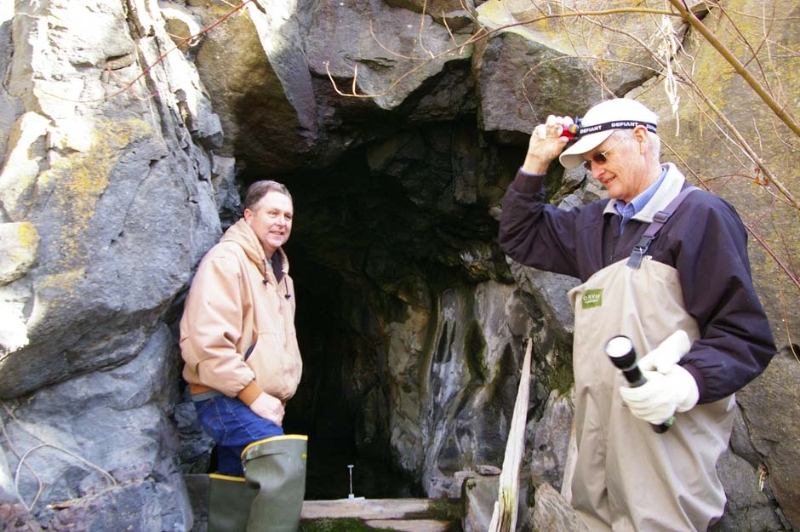

The four of us slosh against ankle-deep water that slowly drains through the underground tunnel.

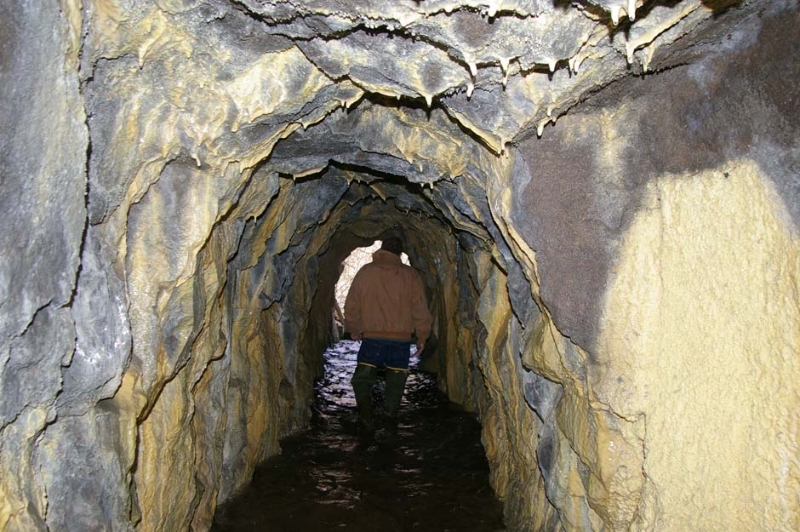

I occasionally look back down the corridor, framed by basalt bedrock, toward daylight entering the shaft’s ever-shrinking opening. I double-check my headlamp. While I don’t feel claustrophobic, underground exploration is not really my thing, and as much as possible I’d like to keep tabs on where I am. I continue to follow the group, fairly confident in the knowledge that two of the others have trod here before.

Water drips from the ceiling and Brian Olmstead, our leader, points out six- and eight-inch drill holes that vertically intersect the tunnel’s right edge, allowing more water to enter the void. After we’ve walked at least an eighth of a mile, the passageway makes a dogleg to the right. A noise that began as a soft hum when we first stepped into the cavern, now amplified by the underground acoustics, has developed into something resembling a rumble. Fully reliant on our headlamps, we continue to the end of the tunnel where we find the sound’s source and the culmination of our adventure. Water cascades down from the ceiling, entering through a seam of fractured bedrock.

A landowner with Brian Olmstead (right) about to enter a tunnel a few miles from Twin Falls.

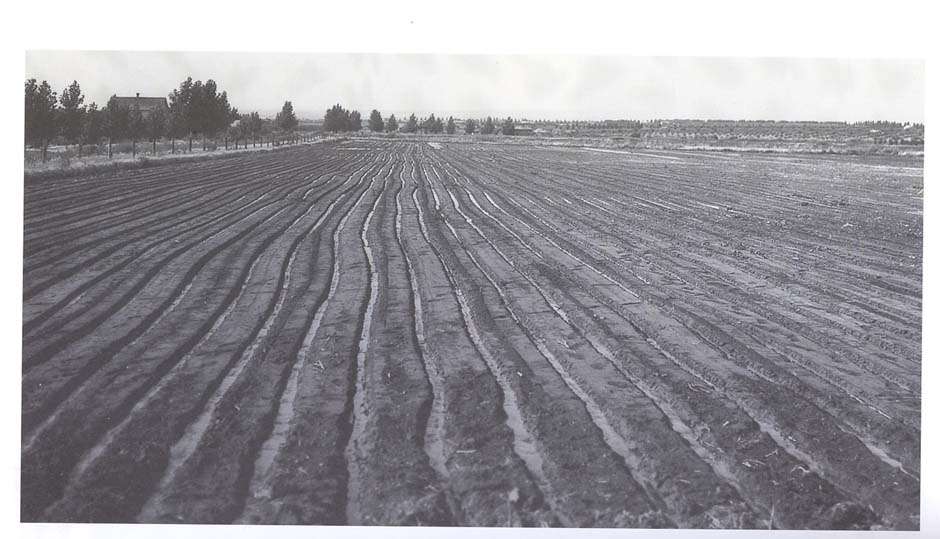

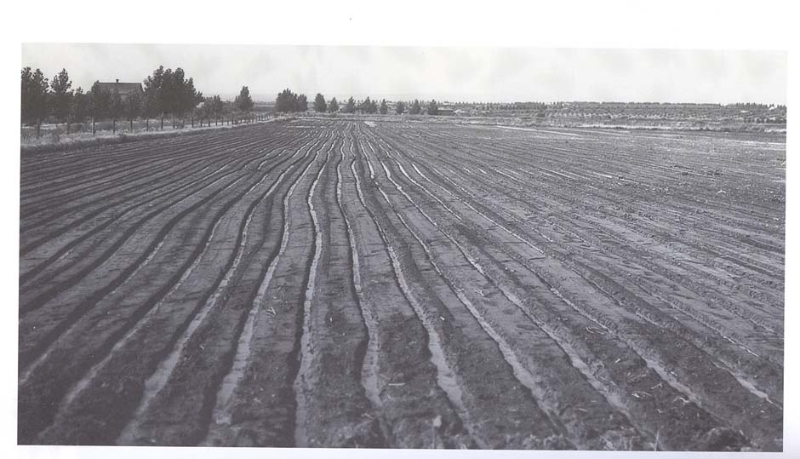

Furrow irrigation around Twin Falls, circa 1910.

Laying seep tiles.

Support beams in the tunnel.

Brinya Olsen, Brian's daughter, at the end of the Claar Tunnel.

On the way out.

The little canyon at Rock Creek.

This man-made excavation, all about irrigation, is an important aspect of one of the largest reclamation efforts in the country. I had heard of the tunnels, but after attending a presentation by Brian about them in relation to my job working with farmers and irrigation, I became curious enough on a personal level to ask, “Can you give me an underground tour?”

Irrigation projects sprang up throughout the arid West in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Water first flowed from the Snake River in 1905, upon completion of Milner Dam near Burley. As water met fertile ground cleared of sagebrush, the desert began to undergo a dramatic transformation. Eventually, the area on both sides of the river became known collectively as the Magic Valley.

Diversions to much of the land south of the Snake became the responsibility of an entity known as the Twin Falls Canal Company. By 1911, however, some converted cropland began exhibiting an unsettling phenomenon that other southern Idaho irrigation projects thankfully didn’t encounter. Excess water, fed by newly formed underground springs, began to appear on the landscape’s surface. By 1914, the issue had forced enough farmland out of production that Governor William Borah sent the Department of Agriculture’s drainage engineer, W.C. Sloan, to examine the problem near Twin Falls.

He concluded that the application of irrigation water over a span of less than a decade had caused the water table in certain areas to rise more than twenty feet per year, to levels that became a problem. In one locale, Sloan reported, “In every case the soil becomes so saturated with water that it is the consistency of quicksand. I could not walk over the ground without sinking to the top of my rubber boots. Everywhere the water seems to be under pressure and breaks out of the ground in small, needlelike veins all over the wet area.”

In his eighty-five-page report, Sloan offered no definitive reason why the underlying basalt rock, spread by multiple volcanic flows millions of years ago, so severely restricted the water’s underground movement. He also was uncertain why the most-affected farmland lay adjacent to the Snake River’s tributary canyons. The water levels in these drainages were well below the elevation of the saturated cropland. No other irrigation projects, in or out of southern Idaho, seemed to share either the same geology or issue. Even though the cause remained a mystery, Sloan predicted that the problem would likely worsen and more acres would become unusable.

The canal company began hiring crews of up to seventy-five men to hand-dig deep drainage ditches and bury loosely connected clay tiles underground, in hopes of providing pathways for the excess water to drain away. Brian, our tunnel tour guide and current manager for the canal company, explained that while these efforts helped, they affected the ground surface no more than fifty feet on either side of these conduits. Building a network of ditches and tiles to fully drain any given area would become extremely problematic.

In 1918, the canal company brought in four drilling rigs to punch strategically located holes up to sixty feet into the ground. Water often gushed from these punctures and into the system of ditches and tiles. But while this was an improvement, the overall effect remained relatively small.

The company approached the problem in 1924 from a new perspective after observing that the wells and deepest trenches, later excavated by motorized equipment, yielded the largest amount of water. This time the attack came down inside Rock Creek Canyon, rather than up above at the land’s surface. At a point where the natural drainage passed through an especially water-logged portion of farmland, workers drilled laterally through twenty feet of the canyon’s basalt sidewall where a small spring exited. After they then detonated a healthy charge of dynamite, water surged from the hole at nearly one-and-a-half cubic feet per second.

The next day the canal company’s board members reviewed the outcome and soon plans were made for creating more openings into the canyon’s walls in hopes of releasing excess irrigation water into natural drainages. By 1926, the company fully committed to excavating a series of tunnels through the wet farmland’s underlying bedrock.

Construction was initiated in 1929 on the Claar Tunnel, the shaft we explored, and followed most of the era’s procedures. Well holes were drilled at one hundred-foot intervals from the surface to a depth of around sixty feet. The mining was then designed to intersect these vertical slots so that water could enter from either above or below. The tunnels usually ranged from twenty to forty feet below the surface and were set at a one percent grade for two reasons: to allow one man, unassisted, to push a filled ore cart back out along the slight decline to the opening and to permit any water entering to drain away naturally.

The Claar Tunnel, however, differed in a couple of ways from the norm. First, the height of the tunnel was constructed at seven feet, rather than the typical six. While no reason seems to officially exist for the difference, our group enjoyed the extra foot—otherwise the jaunt would have required hard hats and a considerable amount of stooping over. In addition, the Claar Tunnel ended after 1,150 feet, well before its planned length, when it intersected that robust shower of water.

Initially, the canal company contracted with hard-rock miners to create the tunnels. Men migrated from places like the Jarbidge Mining District in Nevada and were paid the standard rate of $7.50 per foot. Eventually, the company determined that rather than contracting the work, they could utilize their own labor force more effectively.

Regardless of who toiled away underground, however, the mining was slow, hard, and dangerous. Joe Webster, a long-time employee with the canal company, takes a particular interest in the effort’s human element. He describes a typical morning in the tunnel as mostly a matter of piling loose rock into ore carts that were then wheeled down iron tracks and dumped at the tunnel’s opening.

Once laborers cleared the rubble, they drilled holes for the placement of dynamite and set the charges. After the afternoon’s detonation, no one entered the tunnel until the next morning. This allowed time not only for the rock and dust loosened by the blast to settle, but for any noxious gases created by the blast to dissipate. Progress came in slow increments—the tunnels did not grow by much more than five feet per day.

Over the span of nearly thirty years, seven people lost their lives while working on the tunnel project. Two men contracted pneumonia, likely from a combination of breathing stale subterranean air and working in the damp environment. When a tunnel lengthened and began to function as intended, workers had to contend with water draining from overhead and with the flow at their feet.

Some perished in accidents resulting from falling rock, while others were killed during blasting mishaps. Albert Wavra died instantly when he returned to a tunnel to check on a dynamite charge, only to have it belatedly detonate. Jack Sorensen was injured when at least one blasting cap exploded as he primed a charge. While his punctured abdomen might not necessarily be fatal today, the wound became infected and he died within several weeks.

Usually the people who performed the labor in projects that reinvented the West are nameless, the individuals forgotten or grouped together in statistics. Outside the canal company’s main office, however, an interpretative display that Joe developed contains a list of those who died during the prolonged effort:

1933—WPA Employee

1936—Albert Wavra

1936—Fred Greason

1936—Johnny Denardis

1936—Jack Sorenson

1938—Garland Curly

1942—Benton Reece

In all, hundreds of men labored for several decades to construct fifty-one tunnels to drain thousands of acres of farmland. The underground network totaled about twenty-one miles, with one tunnel under the city of Twin Falls extending for more than a mile. The financial cost to the Twin Falls Canal Company was immense. The $2.5 million spent between 1926 and 1948 was close to the company’s original share needed to dam the river and then construct the delivery system.

With much of the tunnel work occurring during the Depression, the expenditures nearly broke the company. The Works Progress Administration, spawned from President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, assisted the effort during the last half of the decade by helping supply labor.

Today, the drainage system remains nearly entirely intact and functions year-round. The flows that depart from the subterranean web are often re-diverted for irrigation or to help keep hydroelectric plants operational. In some cases the water, having been filtered by its slow passage through bedrock, even supports fish hatcheries.

Since all the tunnel entrances are on private property, they are inaccessible to the public. But while these drains remain virtually unseen and somewhat obscure, they are not anonymous. Each shaft still carries the name of the landowner with whom the canal company contracted long ago, even though that identification often has no association with the current owner. In addition, little remains inside those tunnels that offers a tangible connection to the men who worked there.

Their lasting legacy is simply the empty space that guides its watery collection back to daylight.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only