No products in the cart.

We Dream As We Go

How Vision and a “Can Do” Spirit Erased Poverty among the Coeur d’Alene Tribe

By Robert S. Bostwick

Photos courtesy of Coeur d’Alene Casino Resort Hotel

It began on a wheat field, and not much of one at that. The soil was heavy with clay. Wetlands and thorny wild roses sprouted all around. On these eighty acres near the intersection of highways U.S. 95 and Idaho 58, the Coeur d’Alene Tribe would spin wheat straw into gold—and this was no fairytale.

Over twenty-five years, the Coeur d’Alene Casino Resort Hotel has evolved into a 298-room destination resort with seven dining areas, fourteen hundred gaming machines and bingo in about one hundred thousand square feet of gaming space amid the world-class Circling Raven Golf Club. Visitors from around the world see these results, but tribal members also see a vision realized. They see their children and grandchildren looking hopefully toward the future. They feel their ancestors looking down at them, approvingly and proudly.

I had the chance to watch the progress close-up, as the tribe’s press secretary for eleven-and-a-half years, followed by thirteen years as the casino’s director of public affairs. I remember those eighty acres were just enough when the original building, which housed bingo, opened for business in March 1993. Its thirty thousand square feet offered seating for about one thousand players. There were a few offices, one meeting room, a small cantina, and a lobby. To build it, the tribe borrowed $2.9 million from an economic development fund at the Bureau of Indian Affairs—a fund that doesn’t even exist anymore.

David Matheson, former chairman of the tribal council, who has a master’s degree in business administration from the University of Washington, was the brains behind the boom. He had served President George H.W. Bush over the previous four years, as Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Interior/Bureau of Indian Affairs. He knew all the ins and outs of the gaming industry, and how to start it with bingo.

“I like to tell the story,” David told me. “I got all kinds of advice from very smart and successful people in the region. They all said the same thing: ‘Don’t build it way down there, build it as far north [closer to the Spokane and Coeur d’Alene markets] as you can get.’ Of course, the three rules of business are location, location, location. We had none of the three.”

The tribe also did not have jobs, opportunities, or scholarship dollars. But it did have vision and commitment from an unwavering leadership. At the time, the tribal council included Al Garrick, Dominick Curley, Margaret Jose, Lawrence Aripa, Henry SiJohn, and Norma Peone. Ernie Stensgar was the chairman. Only Margaret, Norma, and Ernie are still living. At the time, the backsides of these leaders were on the line. Their tribe was enduring abject poverty, its unemployment rate hovering around seventy percent.

A hole of Circling Raven Golf Course.

Former CEO Dave Matheson.

![Camera: DCS560CSerial #: K560C-01299Width: 2008Height: 3040Date: 3/30/01Time: 16:27:37DCS5XX ImageFW Ver: 3.2.3TIFF ImageLook: PortraitAntialiasing Filter: InstalledTaggedCounter: [7479]ISO Speed: 80Aperture: f5.6Shutter: 1/125Max Aperture: f1.4Min Aperture: f22Exposure Mode: Manual (M)Compensation: +0.0Flash Compensation: +0.0Meter Mode: EvaluativeFlash Mode: No flashDrive Mode: SingleFocus Mode: One ShotFocus Point: ----oFocal Length (mm): 50White balance: Preset (Flash)Time: 16:27:37.951](https://www.idahomagazine.com/wp-content/gallery/0318-we-dream-as-we-go/DaveMathesonCEO.jpg)

Current CEO Francis SiJohn.

Hole Eight on the course.

The resort's Mountain Lodge.

Bingo at the old casino.

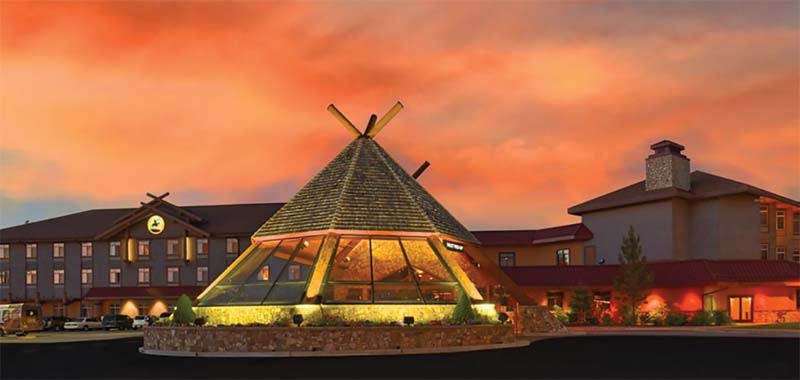

Exterior of the old casino.

Stensgar Pavilion.

Tribal members in traditional garb.

Julyamsh Powwow dancer.

Julyamsh Powwow dancer.

Julyamsh Powwow dancer.

Julyamsh Powwow dancer.

Julyamsh Powwow dancer.

Circling Raven Golf Course Clubhouse.

Hole 17 at the course.

“Oh, we preferred the money issues to the poverty, so we never hesitated to take the risk,” said Margaret Jose, who served on the council six years. Her eyes lit up a bit at the memory. “It sure was exciting, and yes, we did have concerns, but everyone came together then. Everybody had a ‘can-do’ spirit, and so much support from all the tribal families was wonderful to see.”

It was my responsibility to engage Idahoans by gaining media attention to both the tribe’s long-endured economic plight and to its resolve to create a better path. One might expect a brick wall of opposition to casino gaming, given Idaho’s generally conservative nature, but there’s another side to rock-ribbed Idahoans: they’re attracted to the work ethic and what it can bring. Eventually, Idaho would support us, although some folks in Boise were slow to come around.

Leaders in Idaho state government were not at all pleased. In July 1992, the tribe notified then-governor Cecil Andrus that it would seek negotiations for a gaming compact, which was required by the U.S. Indian Gaming Regulatory Act. But in those days, the process often was held up by states dragging their feet. Rather than dragging his feet, Andrus called the legislature into its first special session in decades to write an amendment to the state constitution that would ban all casino-type games. That November, the amendment passed with a fifty-nine percent majority.

Even so, the compact was negotiated in a reasonably timely manner, as casino games were Class I and bingo was Class II gaming, already protected by federal law. The compact also permitted the tribe to run any type of Class I gaming that was allowed in the state—horse racing, mule racing, dog racing (now banned), sports betting, and lottery.

With or without dice, the tribe was on a roll. Then came a few lottery-style machines, mostly in the lobby, and then a few more, which did not fall under Class I casino-type gaming. Revenue was flowing modestly, but expansion was needed, and then completed. Profits mounted. The fifteen-year note for the $2.9 million loan was paid off in three years, and the celebration of it was described in a bingo promotion as a “mortgage burning.” Other such “burnings” would follow.

Success for the tribe proved to be success for the region and for Idaho. Today, about four thousand jobs have been created beyond the Coeur d’Alene Reservation boundaries as a result of the resort’s flow of goods and services. Along with tribal government and other enterprises, this amounts to an impact of some $310 million annually on the regional economy.

The tribe insisted that a provision be included in its compact with the state government: five percent of gaming revenue would go toward education. Over the past quarter-century, these educational donations, which embrace schools throughout the Inland Northwest and even in southern Idaho, total more than $33.5 million.

But the tribe still faced challenges: lawmakers, successive governors, and anti-gaming interests had taken notice. By early 2000, expansions had included a hotel, pool, and restaurants, and fur was flying at the state capitol in Boise. But the tribe was glowingly successful by then, and decided to take the issue to the people.

The tribe successfully petitioned to put another (ironically named) Proposition One on the ballot in 2002 that asked the people of Idaho to confirm the legitimacy of lottery-style machines. A statewide campaign was launched with ample funding. The proposition passed, carrying the conservative state by—guess what?—fifty-nine percent. Idahoans must have appreciated that the tribe had erased its seventy percent unemployment rate and was now at full employment—with more jobs, in fact, than it had among its own people to fill them.

From a bingo operation, the casino had grown into a fifty-room lodge, and then another lodge changed the look dramatically, and the expansions continued so often that few people can now remember which was which. Not only gaming space, lodging, and restaurants grew, but a fifty thousand square-foot events center became a new home for bingo and a venue for concerts, boxing, Christmas parties, job fairs, feasts, and conferences.

In 2001, the tribal council cleared the way to build Circling Raven Golf Club, a stunning vision realized in its own right. The Gene Bates design spreads over 620 acres, winding among woodlands, wetlands, and natural Palouse grasses. It opened in August 2003, and remains listed among the nation’s top one hundred public courses. But the resort’s biggest expansion of all came in 2008, with the addition of ninety-eight luxury rooms, a fifteen thousand square-foot spa, fitness center, lounge areas, and steakhouse, with floor-to-ceiling windows allowing views of the wooded meadow outside.

The Coeur d’Alene Tribe’s diverse and sustainable reservation economy supports some eighteen hundred jobs and boasts health care at a new medical center that serves the non-Indian public as well. Obviously, of the tribe’s roughly half-billion dollars spent on new construction over the years, far from all of it has been spent on the casino resort.

Francis SiJohn took over as CEO of the Coeur d’Alene Casino in 2016, bringing with him a bachelor’s degree in urban regional planning and development and a master’s in planning administration from Eastern Washington University. He is a tribal member and former tribal council vice chairman.

“We’ve done great things as a tribe and as individual tribal members,” Francis told me. “Our promises have been made and kept. In fact, we’ve gone far beyond the expectations of twenty-five years ago, or even ten years ago. And there’s more to come.”

Chief James Allan, the current tribal chairman, maintains the same firm commitment he saw in his elders while he was growing up.

“We continue to create opportunities, jobs, education, health care, and more,” the chief said. “So many benefit from all this, tribal or otherwise—we have clearly shown that as the tribe benefits, so does the region.”

As Francis put it, “We began all this to create jobs, end poverty here, and create dollars for education, for programs and for tribal members to have the same opportunities we see elsewhere. I don’t think we’re going to be complacent. We have the capacity to do more, so I think the time will come to expand again.”

From that scrawny wheat field and the clay beneath it, dreams came true, hopes became reality, success took over from abject poverty. And it ain’t over.

“We dream as we go,” Francis said. “We dream as we go.”

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only