No products in the cart.

Who Was Francois Payette?

A Novel Supplements the Bare Facts

By F.A. Loomis

When I was growing up on our ranch in Valley County during the 1950s, trapping ground squirrels was encouraged, because the rodents ruined irrigation water ditch banks. While I knew of trappers who ventured into Idaho forests for bobcats, foxes, beaver, cougar, bear, and pine marten, I never had the desire to learn more about this trade and always held it as suspect. I loved the occasional brush with a fox, bobcat, or bear in the woods. As a young boy, it was mystical to see wild animals race through ponderosas, buckbrush, and foxtail barley, climb steep slopes effortlessly, and then disappear after running over a rise, not returning to vision on a farther ridge.

Canadian trapper and fur trader François Payette always intrigued me, because central Idaho is dotted with lakes, rivers, and forests named after him. In looking to write something about him, my first question was: Is there enough of a historical record to write a lengthy biography? After all these years after his death sometime in the mid-1800s, I figured a graduate fellow somewhere had already done it and was eager to learn who. However, as I dug through Idaho state archives and jumped through registration hoops to explore internet sources, not much appeared in the historical record, and the information I did find often conflicted. What seemed most accurate about Payette was a rough timeline about where he was on given dates while employed by trapping companies, and sometimes with whom he was traveling.

Without a trove of historical records, it seemed I could at least write a fictional account of his life, using the skeletal timeline of where he was on certain dates. And since accounts are mixed of what happened to him after his service at Fort Boise, I thought it best to cut off the story at 1844, when he retired. After that date, one account has him returning to Quebec following retirement and taking a French-Canadian wife. Another account has him finding his own burial ground on a slope above the Snake River near present-day Payette. As I was not invested with visiting Montreal area cemeteries, I decided to cap my story at his retirement.

The next challenge was: what kind of man was he? The trapping lifestyle is gritty and lonely, so it was important to keep elements of this in his fictional story. There were also key events that indicated aspects of Payette’s personality. Historical evidence shows him personable and cordial, for he entertained Oregon Trail emigrants at Fort Boise, where he was supervisor, when they sought brief refuge and refreshment on their journeys. On at least one occasion he went out of his way to help missionaries construct buildings.

A key event that indicated a quick temper was his documented manslaughter of an Idaho tribal member. He used a hunting knife and was quick to dispatch a young brave who was riding a horse that Payette asserted had been stolen from him. Since Payette had been baptized and confirmed a Roman Catholic as a child in Montreal, I felt it fair to portray him as someone who might have been subsequently troubled by this deadly act. In a creative leap, I had him cross the path of the famous Idaho-Montana missionary Jesuit Fr. Pierre-Jean de Smet to confess and seek absolution for his crime.

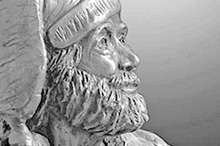

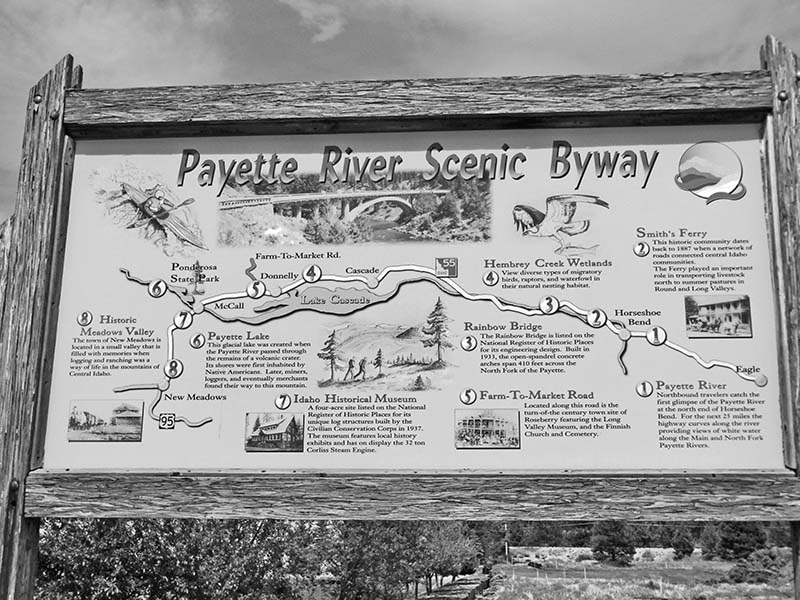

Historical Marker in Cascade. Cosmos Mariner.

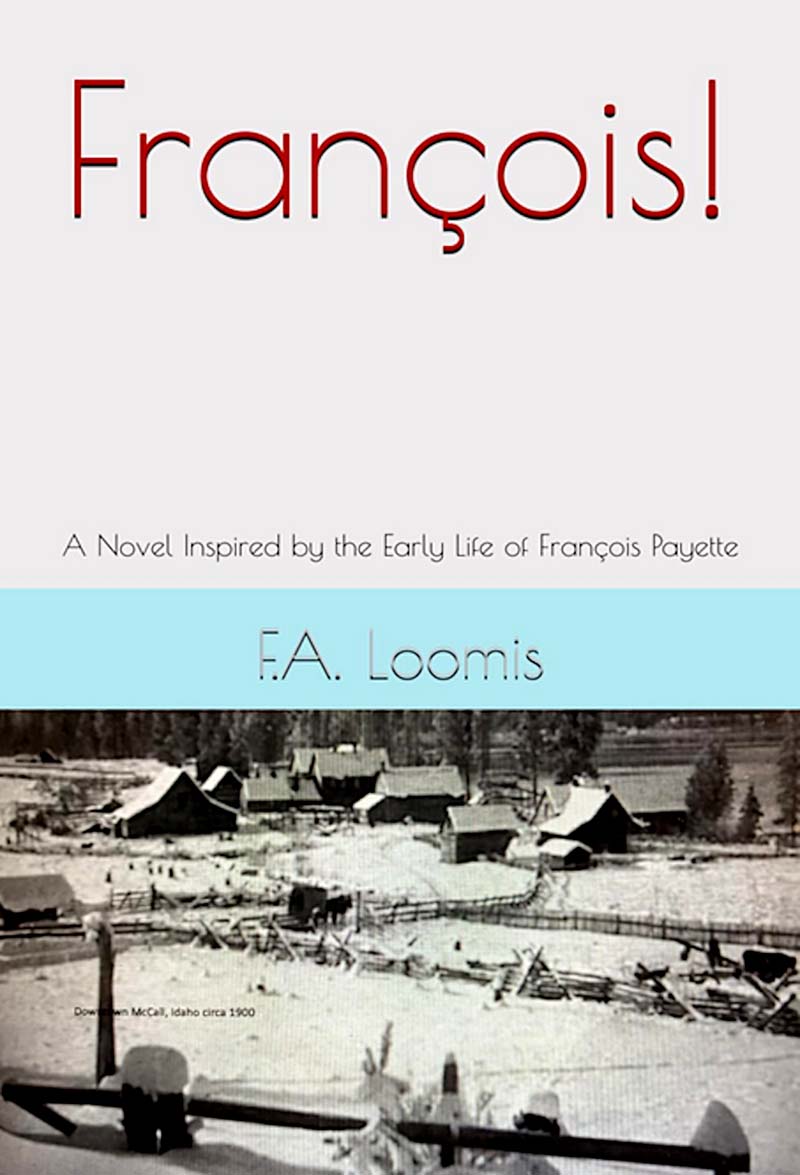

The cover of the new book. Courtesy F.A. Loomis.

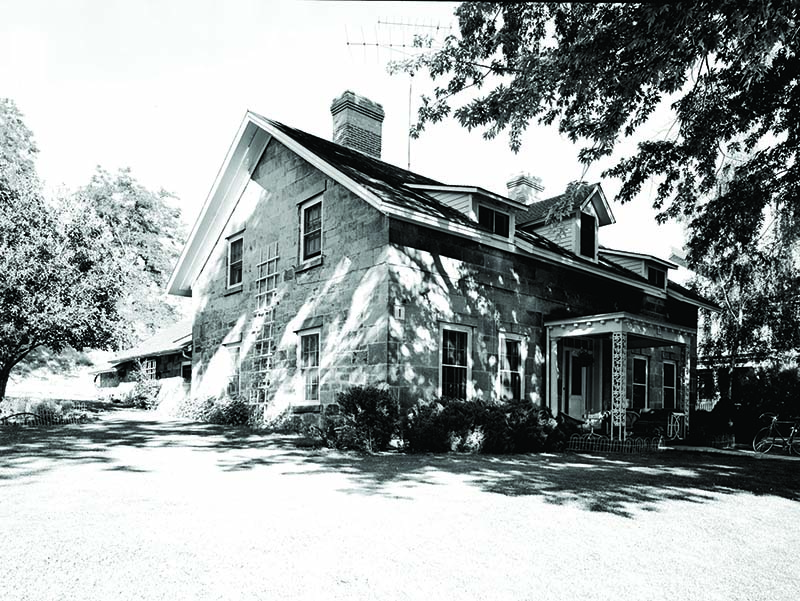

Fort Boise Commanding Officer's Quarters, rebuilt in Boise after the Parma site. Library of Congress.

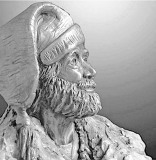

Bust of Francois Payette. Courtesy F.A. Loomis.

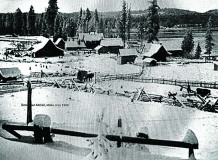

McCall, circa 1900. Courtesy F.A. Loomis.

He was rumored to have taken multiple indigenous wives but I settled on his having one common law wife from the Pend d’Oreilles tribe (related to Salish or Flatheads) and a woman paramour from the Bannocks, each bearing him one child. The historical record shows he may have had more than two children, but the best records indicate at least two. I found no accounts of what became of the children, apart from one that verifies his young son was sent back East to school, so this area of novel-writing left much opportunity for creative conjecture.

In my portrayal of his two female companions, one is the daughter of a Pend d’Oreilles woman and a fellow trapper, and the other is a full-blooded Bannock woman. François meets the Bannock woman in the Emmett area and the Pend d’Oreilles woman while visiting a trapper friend in eastern Idaho. The Pend d’Oreilles woman becomes a common law wife. At least one historical record suggested Payette’s wife, Nancy Portneuf, whose mother indeed was a tribal woman and whose father was a trapper, eventually took her own life, after possibly suffering from a terminal illness. The Bannock woman, Wades-in-Marsh-Water, stayed with her tribe after her involvement with Payette. She is portrayed as grieving in her last years, and therefore becomes a medicine woman who finds comfort through comforting others.

Other elements of the book include fictitious biographies of his two children, a boy and girl, and speculation about what happened to them. One historical account has it that a daughter probably died from measles. In my book, there are also two accounts by fictional characters of dark events in Idaho history: a rape of Bannock women by men obliquely associated with trappers, and a rape of indigenous women by white settler men who lived in or near Emmett. These somber stories show the worst side of the history of settlement by whites. I also make a reference to compassion from settlers toward two tribal children who were found after many of their tribe were killed by white settlers. They were eventually raised in Garden Valley and Emmett by an Anglo family. In Gem and Boise County archives, such a story is well-verified as historically accurate.

In my novel at Payette’s retirement, he tells his life story to a Hudson’s Bay clerk I invented, named N.F. (Norman Freehand) McLeod. This narrative includes references to Payette’s character as I imagine it: his humor, how he dealt with loneliness, and a fun reference to French gourmand tendencies. It would be impossible to portray a trapper as a closet chef, but it’s quite plausible to portray him as a Frenchman respectful of French culinary history. The fame of French chefs François Pierre de la Varenne and Marie-Antoine Carêmel had surely reached Montreal by the early 1800s, when François was growing up. I describe Payette making sausages, favoring fowl and venison ingredients with white wine in compliance with his Champaigne Provincial family heritage, and smoking fish, a technique that French-Canadians perfected after socializing with native American tribes in the Quebec area. The technique became known as boucanage.

When François Payette comes into what is now known as the Payette drainage of Idaho, I depict him entering over the summit above what is known today as Lone Tree Lookout Mountain, just south of Tamarack Resort in Valley County. It would have been a much more arduous challenge to have entered the valley after journeying up the Payette River canyon from the south.

I show him discovering a knapping area atop Lone Tree next to a large obsidian outcrop, where native Americans made arrowheads, knives, and scraping tools. Historically, there was such an obsidian outcropping on the slopes of the Payette River near the confluence of the East Fork and North Fork of the Payette River (near present day Banks). Its remnants are now lost after two centuries of pillaging. Here’s how the scene plays out in the novel:

We found the Payette River by climbing eastward over a long north-south ridge of blue spruce, yellowpine, and lodgepole. At the top of this ridge, we happened upon a broad block of obsidian glass protruding upward from the ground. It was almost five feet in height and as wide as a wagon base. It had flecks of black glass scattered everywhere around it. The Indians had been knapping it for arrow and spear heads, and scraping tools.

Finding it in that location was magical and impressive, because all around it was this beautiful vista of high mountains. It must have been a totemic site for the Indians, I think, even though it was also just a source of flintlike material they could put to work. It was obviously a great resource for tools and weapons, as well as a semi-sacred or sacred place, special et mysterieux. In some blue spruces nearby, we noticed a medicine wheel where it looked like sacred ceremonies had been held.

I thought this was an apt way to introduce Payette to the heart of Valley County in summer or fall. Below he would have seen tribal gatherings to fish and prepare foods for winter along the Payette River between present day Cascade and McCall, and he would have witnessed tipis with smoke and horses grazing in grasses up to their bellies. This is the land where my family eventually homesteaded along the Gold Fork River–Payette River confluence.

Another element of the book is a short biography of a modern-day trapper, Hershel Coulter, whose life contrasts with Payette’s style of trapping yet also has commonalities. Coulter is a descendant of the famous trapper John Coulter of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

I’ve dedicated this book not only to my wife Kristin but also to my great-great grandmother, Corintha Bell Loomis, who was half-Iroquois. As a boy, my paternal grandfather often shared stories about his grandmother Corintha. I incorporated one aspect of her life into the character Wades-in-Marsh-Water, the mother of Payette’s documented son Baptiste: her great cooking skill. Corintha used a waist-high cooking hearth under a bivouac next to her sod house, where she prepared special tribal dishes for her family and made home remedies from local plants. It also was there that she teased my grandfather as a child with wild tales of ghosts and epic tribal powwows.

François! A Novel Inspired by the Early Life of François Payette, is available on amazon.com, at Barn Owl Books & Gifts and at May Hardware in McCall, and at Fiddle Creek in Riggins.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only

One Response to Who Was Francois Payette?

Jeanne -

at

My great great great great grandfather is Francois Payette.

This was very interesting to read.