No products in the cart.

You, Naturalist

Crowdsourcing Biodiversity Data

By Chuck Peterson

Even though Dan Giltz had studied biology at Idaho State University, at first he didn’t fully appreciate the importance of what he saw in the Caribou National Forest. He was on a weekend camping trip with friends at a campground near Idaho’s border with Utah in July 2021 when he encountered a Columbia spotted frog. Dan hadn’t set out that day with the intention of observing amphibians but he used his smart phone to photograph the frog and entered details in an app called iNaturalist, with which he had become familiar when he was an undergraduate at ISU. The app helps anyone to chronicle observations of all kinds of organisms.

Later, Dan learned that the Columbia spotted frog had not been documented in southeastern Idaho south of the Snake River. In Idaho, it’s a species of “greatest conservation need” and its population in southwestern Idaho was once considered for listing as threatened. Several children who were fishing at the site told him they’d seen these frogs regularly—kids always seem to know where to find frogs. Several months later, another observation of the same species was recorded in the same area, possibly inspired by Dan’s sighting. Now that wildlife biologists and managers know a previously unreported population of this sensitive species occurs in southeastern Idaho, we can better plan for its protection.

This shows the value of apps like iNaturalist, through which increasingly large amounts of biodiversity information are being generated, not just by scientists but by the public. For example, since 2002, an app called eBird has provided more than one billion bird observations from throughout the world, providing crucial information on distribution, activity, and population trends. These free apps have made it possible to communicate the public’s extensive knowledge to scientists, land managers, and other community members. The apps have helped to democratize the gathering of scientific data by enlisting the services of many people, typically through the internet, in the process called crowdsourcing. Fittingly, when such research is conducted through public participation, it’s termed community or citizen science.

Nowadays, all this couldn’t be more welcome. We’re currently experiencing a biodiversity crisis in which many, if not most, populations of plants and animals are declining because of threats such as habitat loss, climate change, overexploitation, invasive species, disease, and pollution. As environmental journalist Todd Wilkinson noted, “Without quality data, problems go undetected.”

Here in Idaho, we need to identify conservation problems by gathering more current information on the occurrence and distribution of plants and animals, especially of non-game species. In the past, most of this information was obtained from scientists employed by government agencies, academia, museums, industry, and conservation organizations. A great deal of the needed data was known to someone but went unreported.

Columbia spotted frog. Dan Giltz.

Desert nightsnake. Reepjoel.

Gopher snake road kill in the Boise area. David Pilliod.

The author with a long-nosed leopard lizard. Shaugn Miller.

Northern alligator lizard. Vandal Ryan.

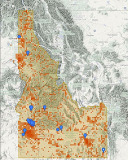

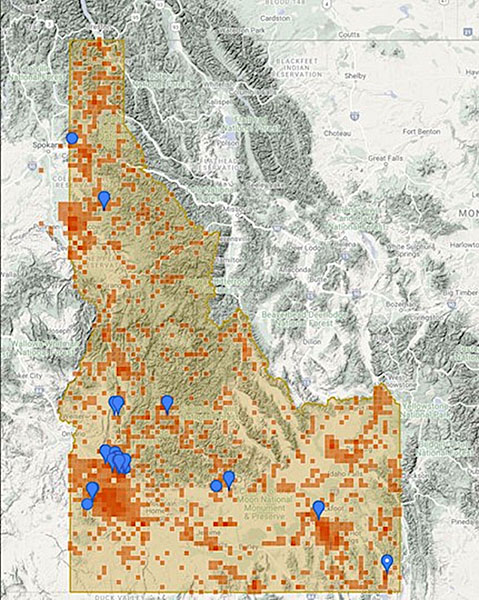

Observations map. Idaho Amphibian and Reptile iNaturalist Project.

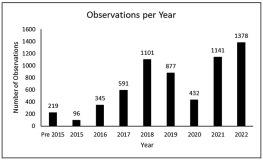

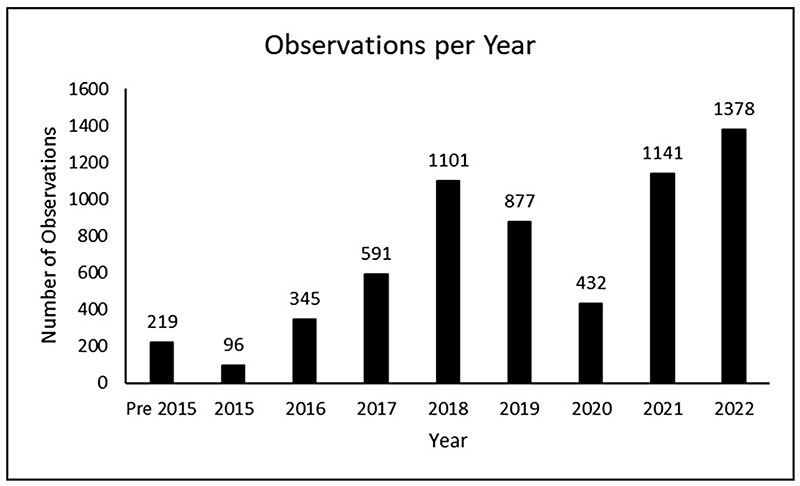

Annual sightings. Idaho Amphibian and Reptile iNaturalist Project.

Dan Giltz in the field. Charles R. Peterson,

Chronicling data. Charles R. Peterson.

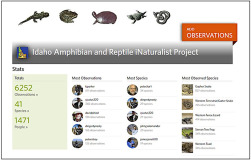

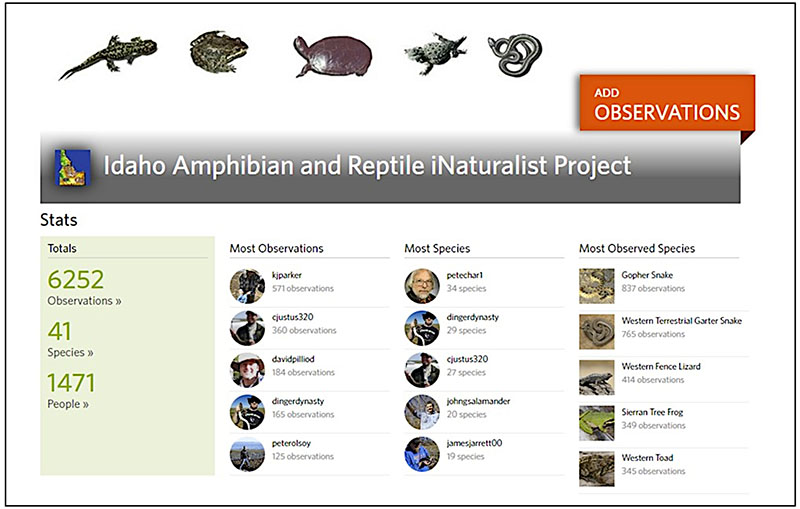

Project website. Idaho Amphibian and Reptile iNaturalist Project.

A red-eared slider. Tomracoon47.

Western fence lizard. Charles R. Peterson.

Western toad in Portneuf River Drainage. Blackrocks.

The iNaturalist program originated in 2008 as a graduate student project at the University of California-Berkeley School of Information and is now jointly supported by the California Academy of Sciences and the National Geographic Society. The mission of iNaturalist is to build a global community of one hundred million citizen naturalists by 2030, which will help to connect people to nature while advancing biodiversity science and conservation.

In 2016, Dan and I created the Idaho Amphibian and Reptile iNaturalist project. We focused on those animals because I study amphibians and reptiles in the Department of Biological Sciences at ISU and, at the time, Dan was an undergraduate student in biology. Out of curiosity and a desire to conserve Idaho’s amphibians and reptiles, we sought a way to get more information for mapping and modeling the distribution of these animals than was available through traditional methods. I took a sabbatical leave to focus on the project and gave workshops and other presentations to recruit participants from throughout the state. Dan’s involvement was funded by the National Science Foundation’s Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR) and ISU’s Career Path Internship Program. While working on his M.S. thesis in 2017-2019, Dan analyzed factors that influenced the number of observations of amphibians and reptiles across Idaho. He established that our recruitment efforts were of primary importance to these observations, even more important than population density.

As of November 2022, more than fourteen hundred observers had contributed more than six thousand observations of forty-one species of salamanders, frogs, turtles, lizards, and snakes throughout Idaho. The presence of all thirty-six native species and five introduced species has been documented. More than six hundred people have helped to identify the species in these observations, which have come from throughout the state but are concentrated around population centers with universities and colleges. Observers for iNaturalist are a diverse group of amateurs and professionals, including students, teachers, wildlife biologists, and the public at large. Each year, more than one thousand observations are added, making this a fundamental source of new information on Idaho’s amphibians and reptiles.

The project is currently managed and curated by Dan and me, plus Charlie Justus, a former Idaho conservation officer. We review verifiable observations—which are those made with digital photographs or audio recordings, geographic coordinates, dates, and times—and we confirm or correct identifications of the species. The rate of misidentifications for “research grade” observations—those in which at least two of three additional users agree on the identity of a specimen—is fewer than two percent. Many students, colleagues, and the public have assisted with the project. We collaborate closely with the Idaho Department of Fish and Game to incorporate the observations into the state’s species diversity database, so they can be used in conservation planning.

Some observations have been quite important. For example, we’ve learned that not only the Columbia spotted frog has a wider state range than had been thought, but so do the northern leopard frog and the long-nosed leopard lizard. We’ve been able to confirm the continued presence of species that are declining, such as the western toad, or ones that are rare, such as the desert nightsnake. Observations recorded on the app have been particularly important for documenting the spread of introduced species like American bullfrogs and pond slider turtles, and the occurrence of road-killed animals. Observations recorded through iNaturalist also have been important for documenting the activity patterns of amphibians and reptiles, revealing that they sometimes are active much earlier or later in the year than we previously believed.

These crowdsourced data can be used in many ways. Knowing about changes in where species occur and when they are active is important in conservation planning, such as developing Idaho’s State Wildlife Action Plan. For example, iNaturalist records indicate that Woodhouse’s toads are still found in populated areas along the Boise River and are more threatened by urban development than was previously appreciated. To document biodiversity in national and state parks, agencies have used iNaturalist to conduct bioblitzes, which are events that focus on finding and identifying as many species as possible in an area over a brief period of time. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has used iNaturalist data in endangered species listing decisions for northern leopard frogs, Columbia spotted frogs and western toads. Road-kill location data can be used for placement of warning signs or wildlife crossings. The United State Geological Survey uses the data to model and map species distributions. In the future, these data will help us understand the effects of climate change on amphibian and reptile distributions and activity periods. iNaturalist data also have many educational applications, including class bioblitzes, learning how to identify species, and providing data for student research projects.

Crowdsourced data have several strengths and weaknesses. Strengths include the large amounts of recent data that can be compiled over a broad area, low cost, accurate spatial coordinates, photo/sound vouchers, and public education and engagement. Weaknesses include the lack of a sampling design and the absence of negative data, which make it hard to quantify observation effort.

Data that are gathered opportunistically, without a study design, are termed “unstructured” and are more likely to be biased, which is the tendency of a statistic to overestimate or underestimate the population characteristic you’re trying to measure. New techniques are being developed to address these weaknesses. It also turns out that large amounts of unstructured data are sometimes better than limited amounts of less-biased, structured data for revealing changes in species distributions and populations. Depending on the question being addressed, the best approach may be to use both two types of data, if they are available.

People use their smartphones or a website to document their observations, which may consist of photographs, recordings, geographic coordinates, tentative identifications, and comments. It takes only a minute or two to make and upload an observation to a database, where it is easily shared with other people and organizations. Photographs are key to iNaturalist in allowing others to provide or confirm species identifications.

By the end of November last year, more than 2.4 million iNaturalist observers had contributed about 122 million observations of greater than four hundred thousand species of organisms from throughout the world. Some of these observations have led to the descriptions of new species or the rediscovery of species thought to have gone extinct. More than 280,000 people helped to identify the species in these observations.

As important as these data are to characterizing biodiversity, engaging the public is equally important. Community science is not only fun and useful, it also increases people’s appreciation of the natural world and their commitment to its protection and restoration. When participants get help with making identifications and in turn help to identify the observations of others, it creates a social network of naturalists. Indeed, public review is important to the quality of the data and is another key aspect of iNaturalist.

Dan and I invite you to give iNaturalist a try. You can use it to document any species of organism that can be photographed or recorded. You also can use the website and app to learn what species are being observed in a given area, get help with identifications, automatically create a list of the species you have observed, and share your observations with other iNaturalists. It’s fun, educational, and it contributes to science and to species conservation.

The free iNaturalist app can be downloaded from the Apple App Store or the Google Play Store. Information on using the app is available on the iNaturalist website. Don’t forge to visit the Idaho Amphibian and Reptile iNaturalist Project.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only