No products in the cart.

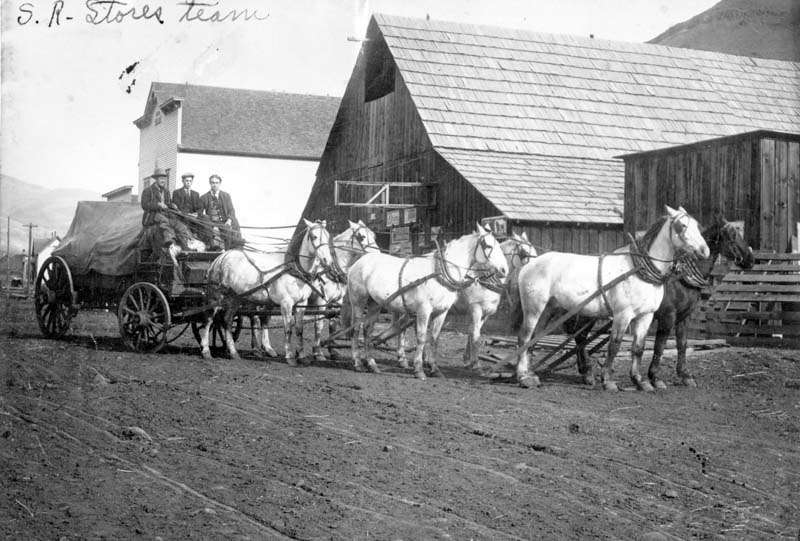

The Freighter

Early last spring, my youngest grandson, Jesse Shreve, and his girlfriend, Tracy Buchanan, rented a place north-northeast of Grangeville, off Lukes Gulch Road.

Looking at my Idaho Atlas and Gazetteer, I noticed another road going north from Grangeville, named “Old Stites Stage Road.” A light went on in my head—this must be the route my maternal grandfather, William Ellis McGaffee, followed when he was hauling freight to White Bird and Slate Creek for the Salmon River Stores Company of Thomas Pogue.

William E. “Billy” McGaffee was born near Ione, in Amador County, Calif., on November 17, 1879. He came with his parents and siblings to Grangeville in the summer of 1883, before he turned four. His father, John Sybile McGaffee, is reputed to have operated the first steam-driven thresher on the Camas Prairie. John Sybile bought a house on the north edge of Grangeville. Sometime in the late 1980s, before my mother, Murrielle McGaffee Wilson, lost her sight, she typed up for my brothers and me many of the stories she’d heard from her father. Here’s her account of how Billy got his early training to be a teamster:

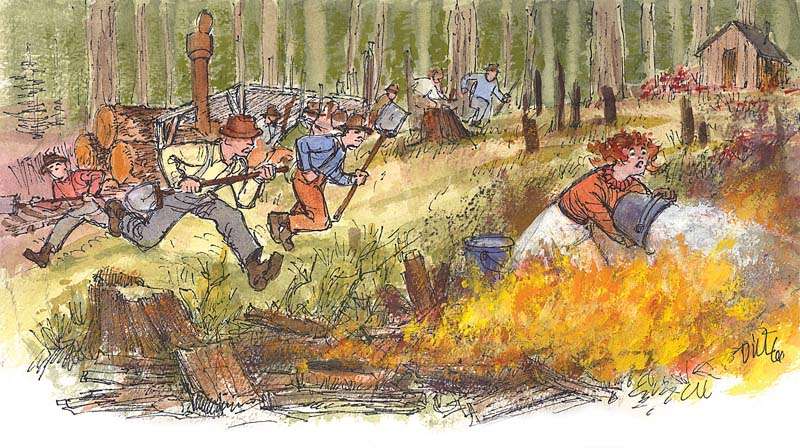

When Billy was ten and Fred [his next older brother] was twelve, their father had just returned from a trip, and at breakfast the next morning he told them,‘There’s a team of black mares in the barn lot. They are yours if you can break them to work.’ The boys rushed out to the barn lot as soon as breakfast was eaten, and sure enough two young black work mares stood with halters on. They started working with the mares, currying, brushing, talking and, of course, giving them a little feed of oats. Continue reading →

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only